My article in this month’s Money Magazine.

It is almost dogmatic to say that politics cannot do much about the economy. Since the neo-con days of the 1980s, the generally accepted maxim is that the less politicians do, the better the economy is likely to fare.

As the phrase “new economic model” is dropped ever more frequently into conversation, given the general dissatisfaction with, and concerns about the sustainability of, the incumbent model, the question begs itself. If not politicians, who is going to imagine whatever the new economic model can be into reality? Are we hostages to fortune? Do we wait for the new model to happen to us only to make the best out of chance or do we as a community on a small bunch of islands have any agency in dreaming our future into existence?

We’ve been at cross-roads before. Leave aside romantic narratives of the counter-revolution during the brief occupation by the French republican guard, Malta’s economy has indeed been what colonial masters made of it. In modern times it prospered on piracy and military construction, in refuelling and repair of a global navy, in tending for the wounded in major conflicts. And it starved on the long peaceful lulls between wars when its vocation as a fortress was surplus to colonial requirements.

The country’s independence promised to change that, to assert our leaders’ authority to design autonomous economic activities concerned only with satisfying domestic interests. This was the 1960s when planning an economy from a minister’s desk was still deemed desirable. Tourism and manufacturing would draw workers away from military redundancies.

In the 1970s, moderate economic planning gave way to iron curtain 5-year plans. The masses of unemployed were rounded up in militarised labour corps. Navy installations were converted into hotbeds of soviet neo-industrialisation. Consumption was engineered substituting imported goods with locally produced imitations. What needed to be imported was purchased centrally, “in bulk” as they called it, to benefit from the economies of scale of government control.

Predictably an economy so controlled ground to a halt, generating depravation and consumer dissatisfaction instead of the intended equality and redistribution. Malta’s 1987 anticipated the arrival of McDonald’s to Moscow. State-owned industries were wound down or privatised. Some interests were “popularised” allowing public participation in ownership but retaining sufficient fragmentation to retain a measure of government control.

And new service industries were founded by the enabling power of legislative creativity. Malta changed its tax regime to create incentives to international businesses looking to hide in a friendly jurisdiction that at the time proudly called itself “offshore”. The same logic of exceptional friendliness to overseas players dodging the heat of their own countries’ bureaucracies was applied to the registration of ships, turning an administrative ledger into a money-making machine.

As the century ran out, Malta compensated its loss of advantage in the industries of the 1960s with economic activities the 1960s could barely imagine. It became harder to find work sewing jeans and gluing soles on shoes. But if you were a lawyer, or an accountant, the world became your oyster.

Meanwhile EU membership changed the rules again. Joining a large free market was flying as far as wings could take us from the dark days of import substitution and protectionist isolation. We changed our tax regime again, modernising it to raise income from added value rather than penalising products merely for arriving in the country.

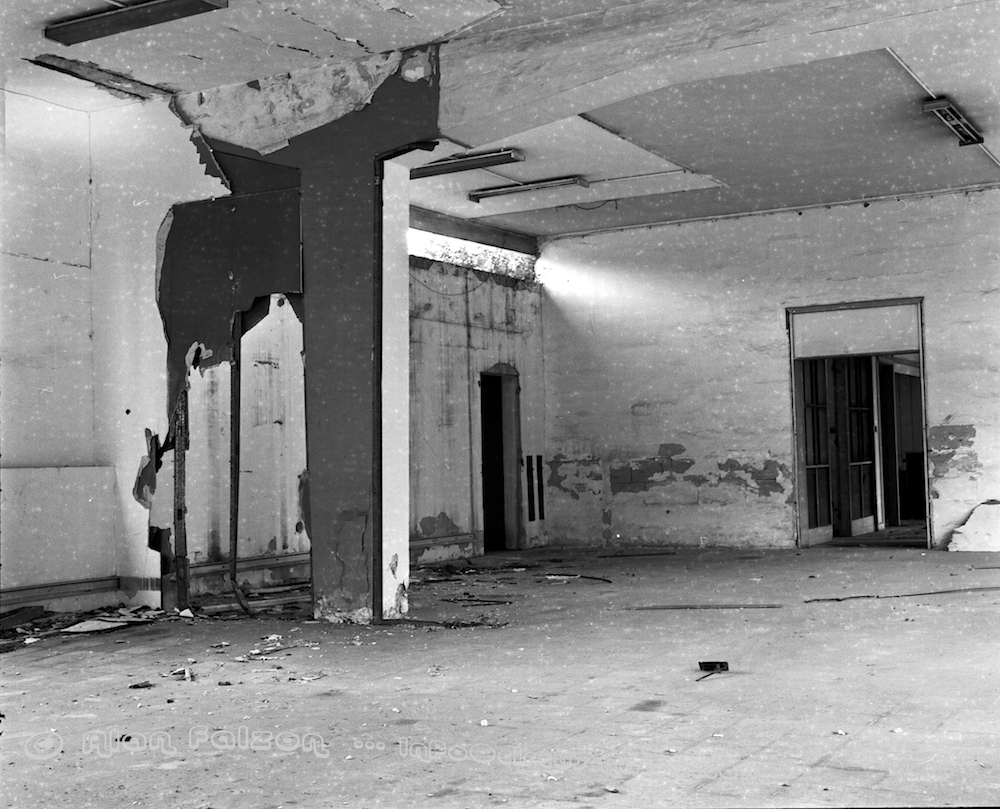

Some businesses floundered. Subsidising heavy industrial legacies from the colonial days was no longer sustainable. The dockyards were privatised. The shipbuilding business, which was neither a business nor did it build all that many ships, was wound down. It was no longer sustainable to grow pigs and the manufacture of blood sausages lost its competitive advantage of operating without hygiene restrictions.

But the bad news of failing low yield businesses was subsumed by the opportunities of access to the European market. And again, creative legislation kickstarted entirely new business streams.

The laws regulating generic versions of pharmaceuticals whose patents were expiring turned the country into a European workshop for Indian chemists. The laws regulating gambling turned the country into Europe’s virtual casino. The laws regulating finance turned the country into Europe’s low-tax high-fees bank.

Malta began to fancy itself a tiger. It lived down the 2008 crisis almost unscathed. It adopted the euro well ahead of other states who wanted to since they joined the EU the same date as Malta. By 2013 money flowed through the country in amounts beyond most people’s comprehension.

The growth reached levels well beyond the country’s ability to police what was happening on its watch. Organised crime used gaming to launder its money. Corrupt dictators used Malta’s banks to hide the money they embezzled from their people.

By 2013 the unfortunate side effect of an entirely open economy that relies on providing its customers with unwindowed rooms, hidden from prying eyes, became the entire point. It was like taking a drug that cures an affliction one is free of for the high that it gives the patient.

This was most transparent in Malta’s scheme of retailing its own passports to people who needed one because they want to hide where they’re from and who can afford it because they are millionaires. The scheme was central to Malta’s latest understanding of its offer: to be a dark cave where pirates can hide their gold-filled chests.

For some time, the passport selling scheme was successful. Hundreds of Russian oligarchs, friends of Vladimir Putin, became Maltese overnight. Until very recently that behaviour, though suspicious, was largely acceptable. Or at least it was acceptable enough to let us get away with it for as long as we did. It isn’t any more. We can’t sell passports to Russians anymore and we’re struggling to find buyers from anywhere else. The passport-selling holiday is nearly over.

We also tried our hand with bitcoin, a latter-day update to the mission to become the repository for money hidden from the eyes of the world. Malta expected it would become known worldwide as the block-chain island. That did not work out. It was one thing to be the first to write laws to enable investment. It was another to build the capability to police such a high-risk activity. Our reputation went down with the capture of our first customers who were, predictably, exposed as crooks. Malta is as much a block-chain island as it is likely to lead the way for the human exploration of Mars.

The winding down of the two solitary attempts for economic re-invention of the last 10 years are not themselves the cause of the disquiet with our current economic model. If anything, the government’s poor record of imagining new business ventures causes us to doubt their ability to replace the consequences we live with on the ground.

In the absence of new economic fronts, we are plagued with unending construction and the irreversible ruination of the quality of the country’s living environment. People have been taken away from ordinary jobs and employed in unproductive public sector employment and they have been replaced by a large, imported immigrant population that fattens our gross productivity statistics. It also increases demand and a creaking infrastructure, permanently behind public money spent on patching it up. The national health service is unable to cope with demand. The country is statistically richer than ever, its people unable to make ends meet.

What comes next? In 1964, 1979, 1987, 2003, and 2013 circumstances made us switch on our creativity, and political leaders came up with plans for our economic future. Some of the plans had catastrophic consequences. The rest are the reason we’re here today.

Find me the politician who is busy planning this country’s future and maybe you and I can feel better about what things may come.