There’s something deeply disturbing about a law that specifically empowers governments to listen in on conversations and tapping the devices of journalists and their relatives. Certainly, it’s a gross invasion of privacy. It also reinforces the slanderous idea that by virtue of being journalists they’re doing something wrong. It is, as it were, a profession that justifies surreptitious state intervention, like bank robbery or conspiracy to overthrow the state.

None of these are the most important considerations on this issue. Likely none of them are foremost on the minds of governments who want to do this. It’s not journalists they want to listen in on. They want to spy on their sources. They want to know who’s reaching out to journalists with matters they want to cover up.

What’s more they want this known publicly, like the deterrent of a doomsday machine. The public knowledge that they have the power to listen to journalists is more important than the listening itself. Because the public knowledge that they have the power to listen to journalists is enough to scare most sources into silence.

It’s the silence these governments are after.

Here’s Beppe Giulietti who heads the Italian Federation of Journalist Unions:

https://t.co/iE2rx6pCru

La possibilità di intercettare i cronisti per ragioni di “sicurezza nazionale” segna la fine della tutela delle fonti e morte di quello che resta del giornalismo di inchiesta @Artventuno @EFJEUROPE @RobertaMetsola @Manwel_Delia @Corinne_Vella @reportrai3— Beppe Giulietti (@BeppeGiulietti) December 13, 2023

“Being able to intercept reporters on grounds of ‘national security’ marks the end of the protection of sources and the death of what remains of investigative journalism,” he says.

I can find no excuse and no justification for any of the governments that are pushing for this. Nor do I have the knowledge sufficient to seek to understand their reasons, such as they may be.

But I know my government enough to know that the insistence of Robert Abela’s government that they’re allowed to spy on journalists is in character. There’s never been reason to suspect that any journalist here has used their profession as a front for some criminal conspiracy. There’s never been anything to suggest that letting journalists do their work without spying on them in any way threatened public safety or the security of the state.

The only risk governments face in allowing journalists to do their work is political risk to themselves. The fact they call it “national interest” when it’s just their personal and partisan interest they are protecting does not change that simple fact. They want to starve journalists of the information that could threaten their political survival.

As Becca Bonello Ghio eloquently put it in reaction to the news, “the country of a journalist murdered for her work wants to undermine the first EU media freedom law.”

The country of a journalist murdered for her work wants to undermine the first EU media freedom law.#Malta, along w/ 🇫🇷, 🇮🇹, 🇫🇮, 🇬🇷, 🇨🇾& 🇸🇪 all support the spying of journalists 👇https://t.co/FQzuRQwMkk@MaltaGov @OwenBonnici @EFJEUROPE @daphnefdtn @Manwel_Delia

— Becca Bonello Ghio (@BonelloBecca) December 12, 2023

Malta should be a champion for media freedom. The government of the state that has been found responsible for the killing of a journalist should be striving to be seen to have turned the page and become the government of the state which advocates most loudly for the safety of journalists. Fat chance.

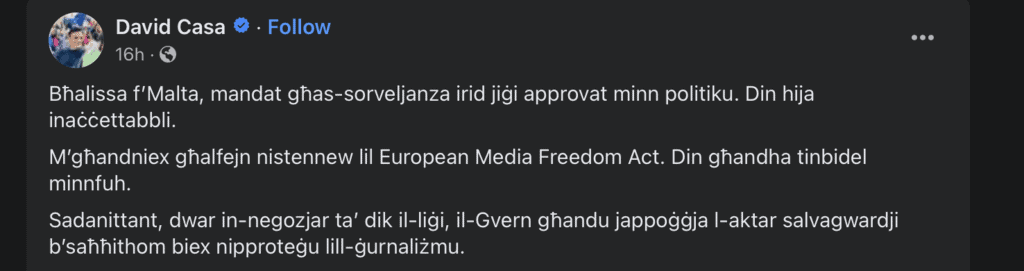

Instead, they want to listen in to our calls. They quite possibly already are. As David Casa pointed out a government minister in this country signs warrants for wire taps without any external oversight.

That is chilling.

We go to great lengths to protect our sources. The Maltese government is looking for a European license to undermine those efforts. It is truly depressing that they’re finding allies in other governments of the EU.