Imagine that. The CEO of a company hands the board their notice of resignation after their position became untenable due to public outcry over their conduct. That happens on 1 December with a notice that expires by the following 12 January by when the board of directors will have found a new replacement CEO.

The outgoing CEO works their notice merely as a formality. They take time out to go on holiday with the family and they’re seen sitting for interviews for new jobs. But on 19 December the board meets and decides to unilaterally change the outgoing CEO’s contract, doubling their termination benefits and wiping away the contractual conditions under which those termination benefits would not be due.

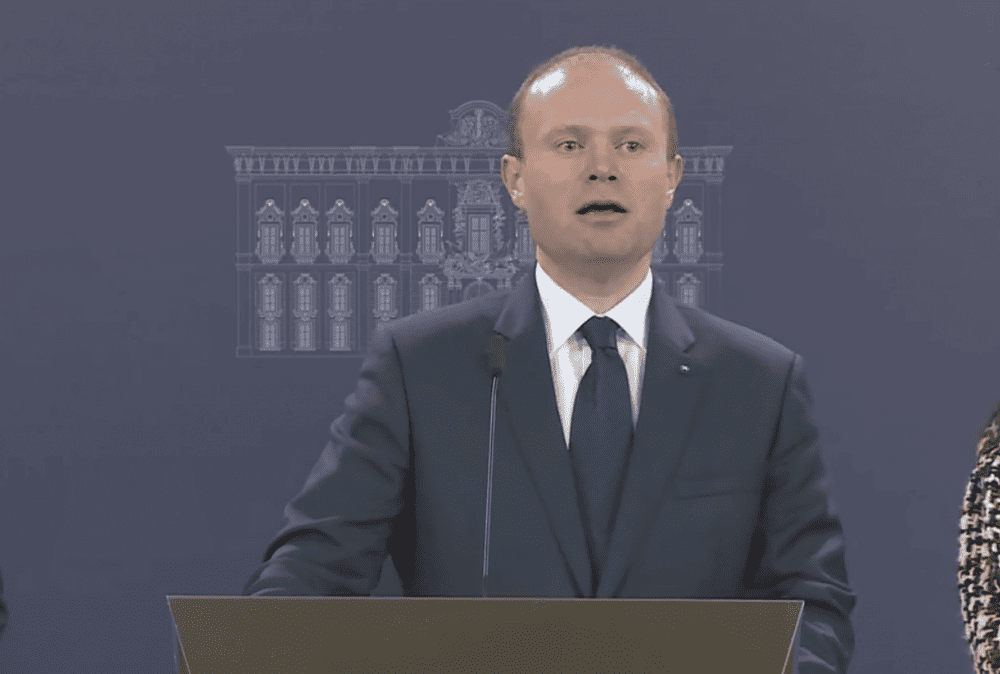

That’s what happened when Joseph Muscat resigned. The equivalent of the board is of course the cabinet of ministers who decided on 19 December 2019, halfway through the period between when Muscat announced his resignation and his final departure from Castille as prime minister, apparently in Muscat’s absence, to double the end-of-term bonus his predecessors got. He got two cars instead of one. He got an office. He got double the cash payment and it was paid to him upfront instead of over a three-year period. And he was paid the full termination benefit even though the previous rules said he would have had to give up most of it given that his landing out of politics had been so soft and he was making so much money as “consultant”.

This is nothing short of daylight robbery. There was a time when Robert Abela would profess disgust at this behaviour. Remember how Konrad Mizzi resigned less than a week before Joseph Muscat but before leaving he set himself up with a consultancy contract with a department in his former ministry? When Robert Abela realised that – or rather when the public realised that and they turned on Robert Abela to see what he would do – the new prime minister cancelled the contract and made sure Konrad Mizzi did not take a penny.

The Commissioner for Standards yesterday published a decision that he could take no action on the way cabinet gave Joseph Muscat an unprecedented financial reward for resigning in disgrace. But his supposed grounds for passing the buck on this one as well are awfully suspicious.

He says he can’t pin this on Robert Abela because when cabinet decided this Abela was 3 weeks away from becoming prime minister. Yes, and? He’s been prime minister since. As head of the cabinet, he had the power (and therefore the duty) to reverse unethical decisions of his predecessor. Isn’t that what he did when he stopped Konrad Mizzi’s self-given terminal benefit? He’s accountable for keeping the system going. He’s accountable for not making Muscat pay back money he should not have been given and for not kicking Muscat out of a government office and for not making him pay rent for the time he’s used it until now. That’s firmly within the Commissioner’s reach.

The Commissioner says he can’t act because the law says he can’t do anything about things that happened more than two years before a complaint is made. Again, rubbish. The unethical behaviour did start more than two years before Repubblika and Cassola complained. But the unethical behaviour was still ongoing when they complained. Muscat still has a second car. Muscat still has the money he was given well beyond what he had been due. Muscat is still squatting on public property. The Commissioner was well within his rights to do something about that.

He may be right on his third reason not to do anything. The law says he can’t interfere with cabinet decisions and in any case cabinet proceedings are secret. There are good reasons for the secrecy. Ministers should be able to speak their minds before having to stand by a collective decision. But that secrecy is not a license to behave unethically. A cabinet decision, though collective, is the product of the behaviour of several single individuals that remain accountable for their conduct.

Did ministers behave unethically when they agreed to pay a disgraced prime minister who had already resigned double the bonus he was entitled to without any basis at law? Yes or no. Did they abuse of their right to secrecy to cover up unethical conduct, especially when Robert Abela lied in response to a request to have Muscat’s termination package published saying, brazenly, that there was no package?

If the law truly makes this behaviour unaccountable, then the law on ethical standards is useless and the commissioner hired by it is a waste of money: unethical in his very being.