Repubblika has warned Members of Parliament that should they adopt the draft law they are currently debating to “regularise” persons of trust in the public service, the NGO will challenge the new law in the constitutional court. Repubblika said it has legal advice that the draft law is in breach of the constitutional rule that safeguards the distinctiveness and the autonomy of the public service by ensuring civil servants are recruited by open competition or in any case through a process overseen by the Public Service Commission.

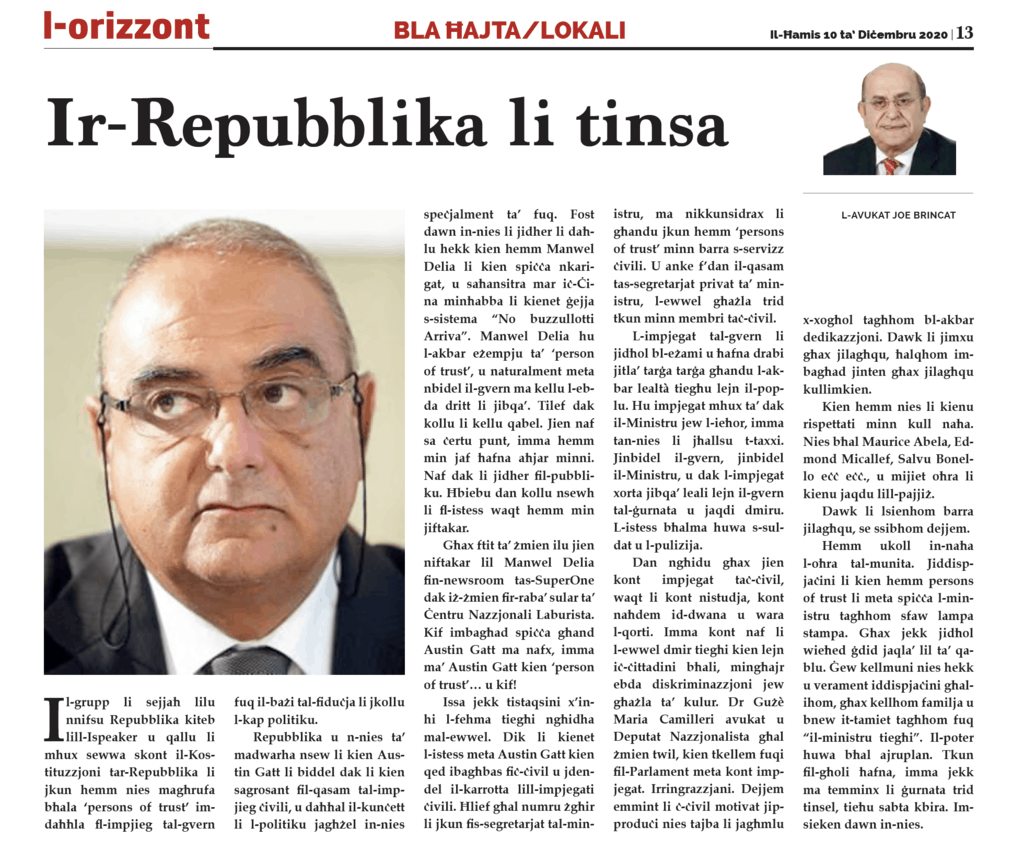

Joe Brincat, the Labour veteran who seems to have developed a minor fixation with me and has been trolling me for a couple of years now, sought to remind Repubblika in a l-orizzont article this morning (scroll down for an image) that “persons of trust” are a creature of Austin Gatt and that I, Manuel Delia, have been engaged in the public service as a “person of trust”.

“Persons of trust” are not a creature of Austin Gatt. There has been a very small number of them in the public service since the 1960s. It is a narrow window ministers have used in the past to hire people they can trust in their private offices. Joe Brincat thinks this is a good thing. He says as much in his article of today arguing that there should be an exception for a small handful of recruits working directly for ministers.

I was one of those recruits that Joe Brincat says he approves of in principle. When I was recruited in 1999 the rule was that a minister could hire no more than two staffers on his personal staff from outside the service, plus up to two others to work as chauffeurs. People recruited on this basis served at the pleasure of the minister, the minister served at the pleasure of the prime minister, and the prime minister served at the pleasure of parliament. If your boss wants you out, or their boss wants them out, that would be the end of that, you’re out.

The system was regulated by policy, which the government is now seeking to make law. It was constitutionally problematic then and it is constitutionally problematic now.

Joe Brincat argues it is hypocritical of me to belong to an organisation that is objecting to legislation that formalises a recruitment system that employed me 21 years ago. I disagree. I would say the opposite would be hypocritical. Here are my reasons.

First, since 2013 we have seen (for the first time ever) how a loophole intended for a handful of staffers that has been around since Independence has been used to crush the soul of the public service. One or two persons of trust in a minister’s secretariat can help the minister in the constants and often futile struggle to bend senior civil servants to their will.

Joseph Muscat’s first decision in 2013, before announcing his cabinet, was to appoint a political crony as public service chief (Mario Cutajar) and fire almost all civil service heads. They then proceeded to employ not a handful, not dozens, but hundreds of persons of trust creating an entire management level on top of the civil service permanent staff.

A dripping crack in the sluice became an open floodgate. By design.

We’re at a point now when, as the Venice Commission and others have pointed out, the civil service has no soul of its own left. By making this system into law the government is asking parliament to go the opposite way of the intention of the constitution.

In arguing that I should not be in an organisation that campaigns against this law because I have been a person of trust, suggests that I must think that everything that existed in 1999 was beyond improvement, above criticism and cannot be re-examined in 2021.

This is the sort of turf-hugging paralysis that slows down structural improvements to the institutions that run this country. Political tribalists in opposition pine for halcyon days when everything was perfect while they ran the show. And political tribalists in government parry any criticism or suggestion for improvement with an “insejtu żmienek?”

Or, as Joe Brincat is doing, criticises a civil society activist for campaigning for legislative changes and compliance with the constitution in their 40s for having served the community in public office in their 20s. This logic seems to argue that civil society activists must be born into a specialist caste, but no one can ever become an activist at some point in their life.

This warped but too often repeated “logic” forces on people a collective selective amnesia and Joe Brincat expects from me to prefer not to discuss the risks, dangers, consequences and constitutional challenges of hiring persons of trust because I had been one.

Well, we’re not going to fix things by thinking this way. Clearly, effective government requires a reasonable relationship of trust and confidence between ministers and their closest collaborators and advisors. But this cannot happen at the expense of a distinctive civil service that recognises itself as such, that ensure that policies remain within the law, that those policies are loyally implemented, that restraint is exercised and that there is institutional memory that is not wiped out with every change of a minister or a prime minister. A person of trust who is due to leave office the day their minister does is not hardwired to care about what happens after they are forced out.

We’re paying for the consequences of a government that is run by people who care for nothing beyond the next election. We have seen some senior civil servants testify at the Daphne Caruana Galizia inquiry confessing to an existence outside the role the constitution expects from them. And we pay for the corruption and mismanagement they are unable or unwilling to stop.

Our role as democracy campaigners is not to seek to argue why our past personal choices are beyond reproach, but to seek to argue how this country can be better served, how its constitution can be better safeguarded and how are democracy works in the interests of those who live in it, not merely those who run it. Selective amnesia then is not in my job description.

One final note. Joe Brincat may expect me to be forgetful, but he remembers things that did not happen. He seems to think I have been in the past a Labour Party activist working in “the raba’ sular” before I showed up as a person of trust of Austin Gatt. He must have me confused with someone else. I came to political awareness when the raba’ sular was the headquarters of the campaign against EU membership. I couldn’t possibly belong to that and that was before the raba’ sular became the hideout of our own petty version of cosa nostra.