On Saturday, Times of Malta ran an editorial that put a simple to understand but rather rhetorical question. Is Malta’s justice system working? Since the question followed a chilling list of documented episodes of administrative, procedural, and technical failures in investigations, prosecutions, and judicial processes the answer cannot be anything but a resounding ‘no’.

Two days later Times of Malta carries two front page stories that could have featured in and lengthened the list of episodes carried in Saturday’s editorial.

It is chilling that the prosecution’s record of conviction has become abysmal. Only 1 in 10 trials, started after interminable waiting and at enormous expense, is now concluding in a conviction.

Successful trials are not only necessary to ensure convictions in the cases they prosecute. They are meant to be a disincentive for other criminals accused of separate cases awaiting trial to discourage them from wagering their chances on an expensive trial. They should instead assume that the prosecutor will prove their crimes and ensure they get a heavier penalty than they could negotiate if they pleaded guilty, or even better agreed to testify against their accomplices, thereby likely avoiding even more trials.

Times of Malta’s two stories of today exemplify the two branches of this problem.

On the one side there’s the story of the prosecution of a case that fell through because prosecutors were too busy elsewhere to show up when the person they accused was charged and then paperwork between different offices did not make it in time to allow for the extension of time limits imposed by the law. A criminal (alleged) walked free because our justice system couldn’t get out of bed one morning.

This shows administrative inefficiencies, bureaucratic failures, and insufficient resources needed for the prosecution service to keep up with the level of crime they are supposed to be fighting.

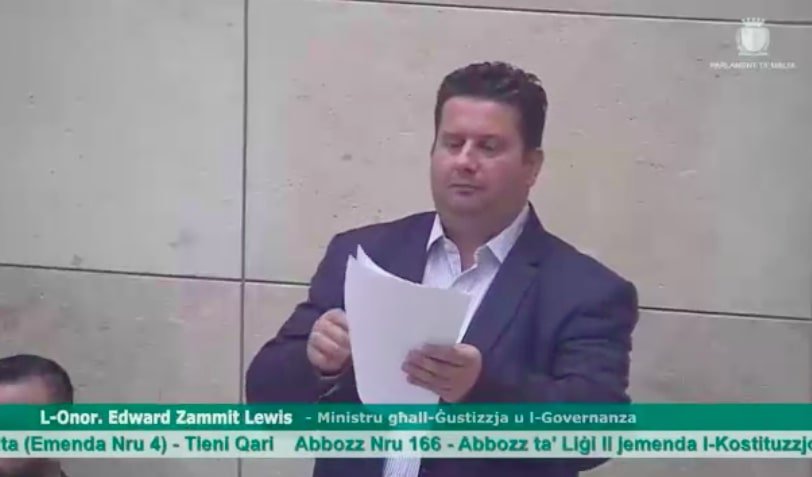

The big issue here is not just that this happened but rather that the government is determined to be oblivious to the problem. When Edward Zammit Lewis comes out of hiding, it is normally to write an article wanking to the mirror congratulating himself for his great reforms in the justice system. The fact that he does not acknowledge there are serious problems in and of itself proves he’s doing nothing to solve them.

Then there’s the other story of hundreds of fines issued by traffic wardens “forgiven” by an unauthorised employee at the enforcement agency responsible. The story says several politicians and their aides are among those who have had traffic tickets issued against them cast into the fire of oblivion.

First question, inevitably, is ‘who?’

The fellow who did this for them has been transferred and is undergoing “disciplinary procedures” which presumably won’t involve making him pay the fines he “forgave”. But this isn’t really about him.

This is about those politicians and their aides who knew about a guy at the law enforcement agency they could talk to, to avoid paying speeding fines or parking on a space reserved for a disabled driver.

Is this as important or as significant as Yorgen Fenech fancying his chances of acquittal in a trial because of an under-resourced prosecution? Is this as important or as significant as Yorgen Fenech calculating he may as well keep secrets about his accomplices to himself since he does not need to waste his currency to deal himself out of a trial that would likely convict him?

No. But it’s on the same spectrum. It shows the rot of law in this country. And it shows politicians’ wilful participation in it because it is convenient for them. If laws against endangering people’s lives by speeding in traffic do not apply to politicians and their friends, why should laws against murder?

The traffic warden thing is a bit of a sore point for me. When the system was introduced in 2001, the political idea was to eliminate the corruption in traffic enforcement that there used to be before. The system was digitised so that all fines would be recorded, an audit trail kept, and no cash would be transferred on the spot. That’s how the system used to be handled by the police before wardens came. If you were nice enough to whoever you needed to be, the record of a fine issued against your name could be expunged.

The new traffic enforcement system was delegated to Local Councils (many of them run by Councillors from the then opposition Labour Party) so that too many people would know if some big shot had their fines cancelled by someone on the inside. It just didn’t happen because it couldn’t happen. Transparency does not remove the temptation of corruption, but it makes it impractical.

In comes this government who takes traffic enforcement away from Local Councils and sets up an agency run by its cronies instead. That way they won’t have to worry about traffic laws applying to them because nobody unfriendly is looking.

Corruption is indeed everywhere but public structures can be designed to avoid it or invite it. The government is responsible in this case for dismantling a structure designed to avoid corruption and replacing it with a structure designed to invite it.

When wardens were first introduced 20 years ago people complained because they could no longer drive or park as they pleased. There were now enforcement agents whose job was to make sure people stayed within the law, at least within faint painted road markings.

Now, if you know a Ministru, or if you are the Ministru, you don’t have to worry anymore.

And that sums up the state of the rule of law in our country.