Alfred Sant jumped to the defence of Mario Philip Azzopardi and said that the Manoel Theatre’s decision to cancel Azzopardi’s play mocking and slandering Daphne Caruana Galizia was an act of pre-modern censorship.

These are the playwrights of the self-proclaimed left that would have been entirely comfortable in the official theatre of communist DDR or some other satellite of the USSR. They call themselves socialist but are in fact statist, using theatre as a tool of state control, of semi-official propaganda, and of violence and intimidation.

The cancellation of the play by the Manoel Theatre board was not an act of censorship. It was the completion of a misguided act of mismanagement that started with the abortive acceptance of the play in the first place.

This was the moment when they hit the ground having slipped on a banana peel they casually threw on the floor when they thought that women-hating, perpetually angry, boulder on his shoulder, Mario Azzopardi was the right playwright to reference Daphne Caruana Galizia on the national stage.

Ix-Xiħa is subtitled ‘dramm anarkiku’, in yet another burst of upside down and poorly understood rhetoric. Anarchism defies governments and centres of powers, not accept their payment to brutalise people who criticise them.

The national stage will no longer offer a platform to Mario Azzopardi (unless a new management board reverses the reversal), but you can bet your bottom dollar that Mario Azzopardi will find another way to fund the performance of his play and stage it elsewhere. He no doubt has the right to do that. The right to free speech is meaningless if that does not include the right to mouth hateful propaganda.

But Mario Azzopardi is interested in far more than his right to speak. If that’s all he wanted, he could speak like I do, at his own expense, defending himself against lawsuits. He could speak as Daphne did until someone breached her right to free speech by blowing her up in a car bomb.

And, I rather suspect, that will give Mario Azzopardi an idea. If the government won’t pay for a propaganda vehicle on the national stage, he’ll find someone else to do it in some other fancy venue. Do you want to bet that he’ll get money from Yorgen Fenech and his family and claim his play has been “crowd funded”?

For it is not only the government that benefits from the idea that Daphne was so utterly despicable that she deserved to die.

After all that was indeed the principal finding of the public inquiry into Daphne’s killing: that her dehumanisation and the lies said about her helped her killers reach her, kill her, and expect impunity for doing so.

They still expect to get away with it and that’s because the hatred of people like Mario Azzopardi still makes it easy for them.

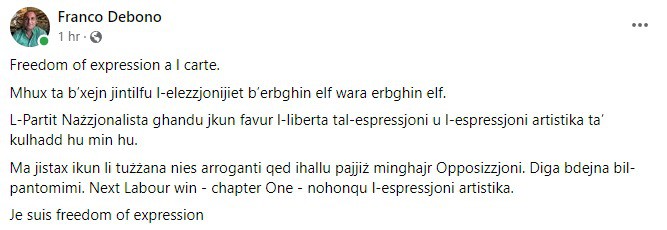

Mario Azzopardi was not alone. Karl Stagno Navarra, Franco Debono, Alfred Sant, and other satellites of the extended interests of Yorgen Fenech and the mafia that killed Daphne, flipped the narrative, saying that it was protesters who “cancelled” Mario Azzopardi and “censored” him like hypocrites who think freedom of speech only applies to them and nobody else.

Mario Azzopardi himself brought up the example of Charlie Hebdo, the inveterate and habitually offensive satirical magazine defended by free speech campaigners when its staff was killed in revenge attacks by Muslim extremists. Charlie Hebdo mocks politicians, religious figures, gods it deems false. It is on the side of the common woman, the oppressed, the victim. Charlie Hebdo mocks the mafioso, not their victim.

It should not surprise anyone that a publicly funded official playwright, and his publicly funded official propagandist allies, should reason this way. That is how Owen Bonnici defended Jason Micallef’s outbursts against protesters calling for justice for Daphne: that Micallef, a government official, was exercising his right to freedom of speech.

Fundamental freedoms are there to protect citizens from their governments, not the other way round. Satire is a tool to bring down tyrants, not their victims. Siding with the killers of a journalist against the journalist is not the exercise of freedom of speech but complicity in the murder.

In between the mafia and its victims, you cannot be neutral, not even with artistic license. A film that justifies the Holocaust of the Jews and glorifies Adolf Hitler (to make a purposefully exaggerated rhetorical comparison) is not protected by artistic license and freedom of speech. A play calling Jews vermin and justifying their mass culling has no place on the national theatre of any country.

So yes, there are situations where artists should, of their own accord, exercise self-restraint and act within basic limits of humanity if not good taste. Having said that, unless they are inciting hatred or violence, artists are free to exceed even the most basic limits of good taste. The obligations on governments, sponsoring these atrocities, are more complex.

Alfred Sant dismissed the argument that the state-funding of art should influence its content. Again, he’s turning the argument upside down. The fact is state funding of art influences its content in unacceptable ways already. The national theatre has not sought to fund performances and artistic representations for our community to confront the brutality of Daphne’s killing and the documented responsibility of the state in enabling it. They have taken their funding elsewhere, on themes and approaches that ignore this great trauma in our collective experience as a country, thereby making it deeper.

It would be inconceivable for the Malta Film Commission to fund the making of films about Daphne’s life and times, and about her brutal killing. It is unimaginable that the Culture Department sponsors playwrights to write satires exposing Joseph Muscat and Yorgen Fenech for their embarrassing and bloody ménage à trois with Keith Schembri.

That is where the notion that state funding should not be an obstacle to artistic freedom and autonomy from official policy would be perfectly apply. Instead, state funding here has been invested in an act of lying propaganda that has already been found by a 3-judge inquiry to have partly caused her death.

I have been credited by the likes of Karl Stagno Navarra for the cancellation of Mario Azzopardi’s play. They flatter me. But if I am to have a minor role in this drama, the play has been cancelled not because of some act of censorship but rather the opposite. The outcry happened because, if anything, I promoted the dissemination of the play by publishing it far and wide.

Although I hate the play and its content, I did not cover it up. Rather I showed people what to expect with paraphrasing the dubious writing of the artist. The fact that on seeing it some people lost any appetite for watching the play being dramatized, is not to my credit but exclusively the merit of Mario Azzopardi who wrote it.

They did not decide to despise it because of what I said about it but because of what it said about itself.

That doesn’t mean there is no market for Mario Azzopardi’s play. As with the election result, I will be taunted when large crowds flock to see it when Mario Azzopardi produces the play elsewhere, rolling those big, broad, blue Doktor Mengele eyes as the cash rolls in. They’ll say he won and I lost because more people will have gone to see his “underground” play than ever would have gone to see it at the Manoel Theatre.

Yes, I can see that happening. What those who taunt us won’t see is that they would be measuring what they consider our failure against the ambition they imagined we were setting: censoring the play. We’re not a government, or a church, or even a government-appointed theatre management board. We can’t censor anything even if we wished to.

We’re just readers, and theatregoers, and citizens, on whom Mario Azzopardi’s right to offend has the inevitable effect of offending us.

But watch this video of Karl Stagno Navarra and understand that the expectation is for us to remain silent when we are hurt, for us to weep silently when we are insulted, for us to shut up when a journalist who exposed them is killed, for us to feel the shame when they dance on her grave.

How’s that for pre-modern, Alfred Sant?