The Constitutional Court presided by Judge Toni Abela ruled today on a case I brought in September 2020 after I was denied reasonable access to assess living conditions in the prison and in detention centres. The court ruled that the government breached my fundamental right to free expression when they refused or ignored my requests to visit cells, toilets, showers, and recreational areas in prisons and detention centres and denied my request to take photos of these sites.

Judge Toni Abela ordered the director of prisons and the director of detention centres to allow me to visit these facilities without the restrictions of previous visits. He qualified that order by saying that I should be kept away from detainees convicted of or charged with the murder of Daphne Caruana Galizia for reasons the judge described as “obvious”.

The court recognised that the directors of these detention institutions have the authority to decide who can enter these secure areas. But that authority cannot be applied on a whim. In an implicit reference to the attitude of then prisons director Colonel Alexander Dalli, the judge said there’s no room for people thinking “I am the king; I am the law”. The court also dismissed the defence that journalists are not listed in the laws that say who has access to the prisons.

It doesn’t matter that journalists are not listed in the regulations, the court said. What matters is that the right of journalists to gather information on the conduct of the government is protected by the Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights. The court quoted extensively from several decisions of the Strasbourg court pointing out in one instance a ruling that said “that freedom of expression does not stop at the gates of army barracks or of prisons.”

Having testified in court that I was not looking for monetary compensation but merely for the court to declare a breach of human rights and to take measures to stop and reverse that breach, the court did not order the government to pay me financial compensation but the court billed the costs of the case to the government.

The court also relieved the Justice Minister and the State Advocate from responding to the case because it was the court’s opinion that the directors of the prison and the detention services had the responsibility to allow me access to the sites they ran.

The case is subject to appeal.

This is a major win for journalism in Malta. It makes it clear that the state is obliged to provide access to journalists, even journalists that are habitually critical of the government. Access for journalists is in this country not only restricted in prisons and detention centres but in many areas of the government’s activities. Today’s court decision underlines the obligation of the government to remove those restrictions and provide journalists with access. The government must submit itself to scrutiny even by people it does not like.

Judge Toni Abela seemed to suspect that the decision to deny me access to the prisons and detention centre was more about me than about anything or anyone else. He says: “Sometimes the state resists not so much because it has something to hide but more to spite a particular journalist.”

Be that as it may, the court recognised that the allegations I was looking to investigate were very serious in themselves. I wanted to investigate persistent and credible allegations of degrading and inhuman treatment of prisoners and migrant detainees and allegations that prison mismanagement was leading to suicides and deaths in prison.

I argued in the case I brought that my right to free expression (and therefore my right to fulfil my obligations as a journalist to report freely about government conduct) is a safeguard for detainees’ right not to be tortured. If the state takes away my right to do my job as a journalist the right of detainees not to be tortured is threatened.

This is therefore, and perhaps more importantly, a win for people who are vulnerable to human rights abuses precisely because they are in the custody of the state.

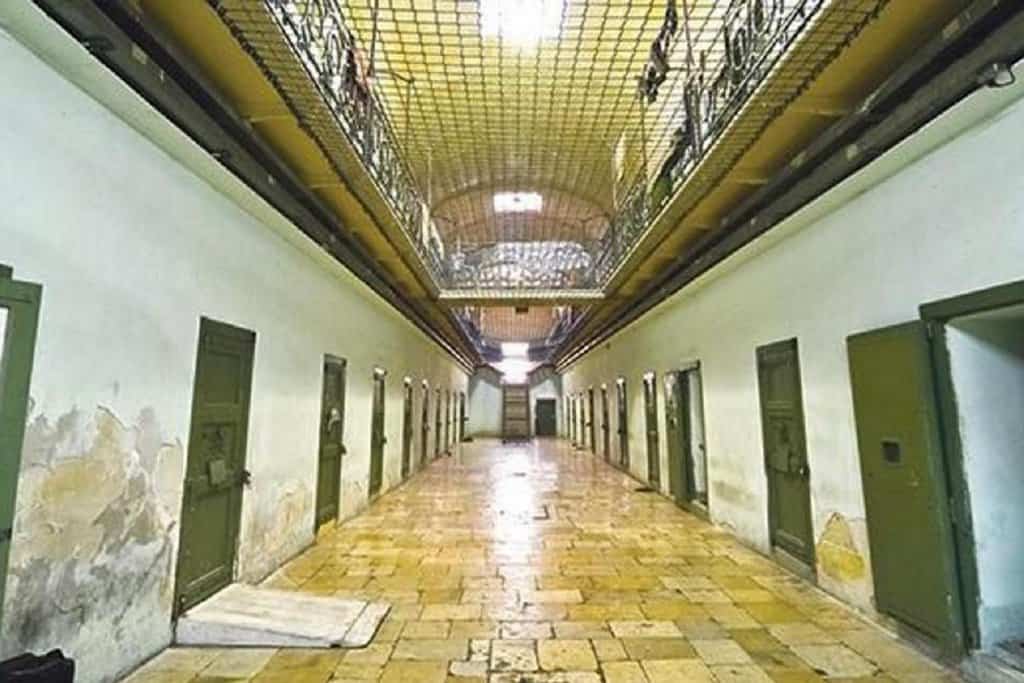

The court underlined the context of the story, and it is worth recalling. In the summer of 2019 over a hundred migrants were dragged to court in a long chain gang out of Roots and charged with damaging public property when they set fire to their own beds at the Safi barracks. The court ignored their claim that the fire they started was the only form of protest the public could be made aware of. In Safi, they were trapped inside a hell hole kept under inhumane conditions that degraded and tortured them. They had no one to speak to about that. They had no means of raising the alarm about their condition. They had no way to bring about any improvement to their detention.

Their suffocation led to their despair. Despair, as they saw it, justified violence.

The court which heard those arguments found them guilty and sent them to prison in Kordin. They were stripped naked and hosed down in the prison courtyard, again a scene out of Roots. They were crowded in cells far beyond the rules, made to sleep on the floor, kept barefoot. Truly horrible.

Journalists working for Times of Malta reported all this and asked the authorities to confirm or deny the information about what was happening behind those bars. The authorities denied. We were all asked to accept that denial on trust. I didn’t.

For months I asked to see for myself the conditions in Safi and Kordin. For months I was ignored and pushed around. Then after a silly incident involving the legendary Terry ta’ Bormla and that Neanderthal Alex Dalli, I was invited to visit Colonel Bloodthirsty at his office in the prison. I wrote about that here.

I could have dropped the matter then but sometimes being stubborn pays off. Sometimes letting things drop is just how you accept the unlawful limits the government imposes on fundamental freedoms. Sometimes dropping an argument and giving in to government oppression is just how you unwittingly expose vulnerable detainees, migrants, and prisoners, to torture and violence at the hands of petty tyrants like Alex Dalli.

Let’s be fair, though. There’s never been a time and there’s never been a government in the history of this country where journalists were allowed access to detention facilities to form their own judgement about detention conditions. The present government was following in a long tradition which, as Judge Toni Abela observed today, has been superseded by Strasbourg rulings that make it clear that free speech can only be restricted based on good sense and reason and in a way that limits as much as possible any encroachment on the right to free expression. Just saying no to journalists wanting to visit prisons and detention centres is not reasonable.

The government now has the choice between implementing changes in its policies to guarantee the freedom of journalists to scrutinise its conduct including with people in its custody or to seek to have today’s ruling overturned after appeal.

I am delighted however that a minor front in the great battle for journalistic freedoms in this country has inched forward if only by a little.

I am grateful to Eve Borg Costanzi, Paul Borg Olivier, and Andrew Borg Cardona who articulated my vague indignation at the government’s behaviour into sound legal argument. I’m only good at starting lawsuits. It’s my patient and able lawyers who fight them for me.

I want to thank Matthew Xuereb and reporters at Times of Malta who first investigated conditions in prison after the 2019 rebellion in Safi and whose work moved me to follow up this case.

I want to thank my sources who shall remain unnamed but who know the risks they took in speaking with me may have – one hopes – led to more than my reporting but have rather eased the pain of a detainee in a way that would have prevented one more suicide.

I want to thank my colleagues at the Aditus Foudantion whose work with detained migrants is inspirational and my colleagues at Repubblika, Occupy Justice, PEN Malta, the Istitut tal-Ġurnalisti Maltin, and the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation whose struggle for free journalism this court case is a small part of.

I also want to give thanks to donors to this website who have supported me in this case as with others.

You lose some. But you win some too.