When you’ve just won a court case, you’re a poor judge of the qualities of the judge who ruled in your favour. Almost as poor a judge as you would be of the judge who just ruled against you.

You must take my opinion of Judge Toni Abela with the seasoning the context I’m in requires. God knows I’ve criticised the man and I’ve criticised his appointment. Even as this case he decided this week was going on, he featured in this blog with less than high praise.

You must also take my opinion of his decision this week in the context of the simple fact that I thought I was right. I didn’t think I was asking for the impossible. I am simply convinced that any reading of the constitutional right to free expression and any reading of the state’s obligations towards people in its custody would tell you that the government’s policy of restricting access to journalists is unlawful.

Having said all that, it needs saying that Judge Toni Abela’s decision this week required moral courage. There are several reasons for that.

Firstly, detained migrants and prisoners do not enjoy the love and sympathy of many people. Just look at the social media comments under reports of Monday’s ruling and you’ll find very little concern for the conditions in which detainees are held. Lack of concern for them drives people down the illogical thinking that the government should be able to hide its abuses to avoid bleeding heart journalists and activists from forcing the government to behave appropriately. Consider one commenter who asked rhetorically if migrant detainees expected three meals a day on top of visits by reporters.

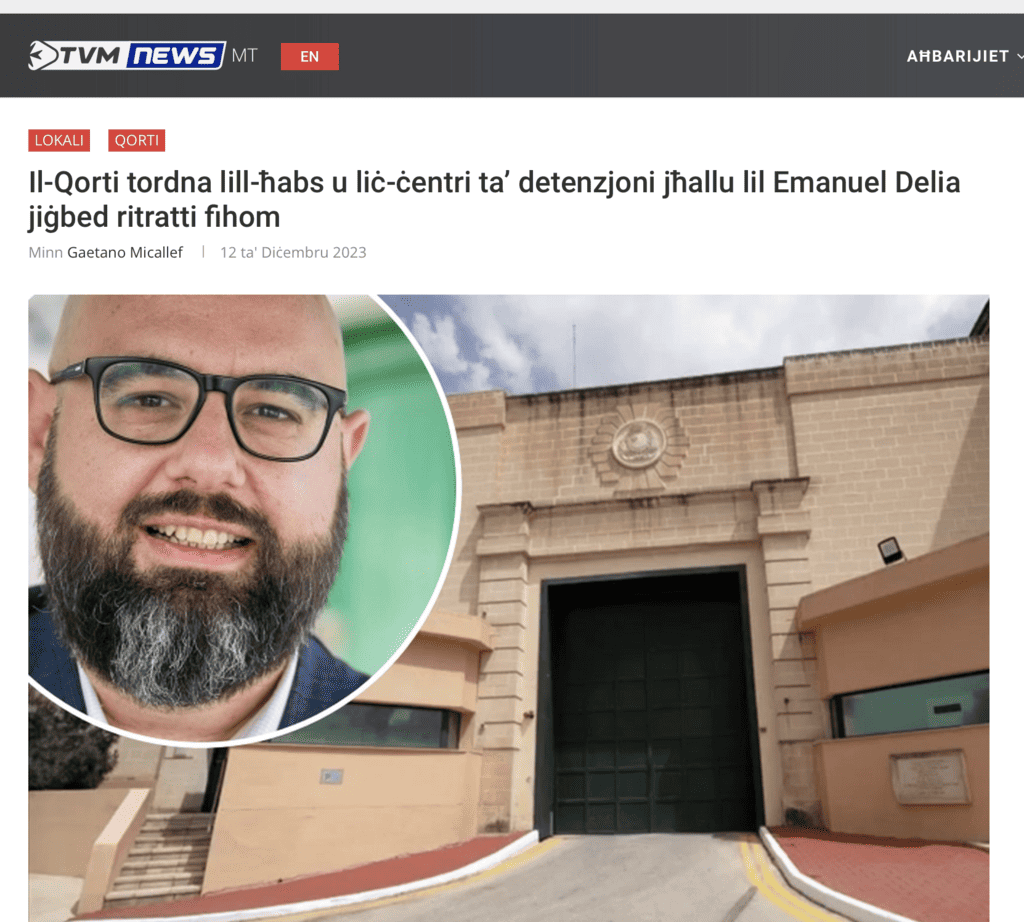

Secondly, I’m not the most popular guy either. Consider this deliberately trivialising click-baiting headline on Malta’s public broadcasting.

Reduced to Manuel Delia’s “rights” this is a story of an annoying government critic being given privileges he has no right to expect. The comments boards were replete with this sort of talk. Particularly the comments under Malta Today’s report which happened not to identify the judge as Toni Abela and led commenters to assume that I won the case because the judge was some anti-Labour sympathiser. Echoes of Robert Abela’s recent speech where he said that “nationalists play home” in court abounded.

Perhaps Judge Toni Abela knew the plaintiff in this case is professionally annoying. Perhaps he’s had himself good cause to be annoyed by the plaintiff in the past and while the case was going on. Perhaps that is why he needed to point out in his judgement that it did not matter how habitually critical of the authorities the journalist is, the duty of the state to provide access to journalists does not change.

Thirdly, there still is some debate on whether I’m a journalist at all, certainly judging by some of the comments online. Commenters described biblical scenes of total chaos as they interpreted the court ruling to mean that anyone with a Facebook account could stroll through the prison gate without warning to sojourn in solitary.

This too appears to have been anticipated by Judge Abela. His ruling spends some time discussing what is a journalist and not to get lost in detail, after some reflection, decides that whatever else I may be, I am a journalist. Some might say that decision alone is controversial.

Fourthly, the excuse of the authorities that they must be allowed to provide safety and security without the hindrance of pesky journalists is often impressive enough to even keep judges at bay. Judges are presumably relieved their job stops at ordering someone is sent to prison and that it’s not their job to keep prisoners locked up. That could create the thinking that the judiciary should stay out of the government’s hair and not impose conditions which make the hard job of being prison chief any harder. If Judge Abela shied away from what the government would describe as intrusion on its space, he would not be the first to choose timidity over the law.

I had a feeling Judge Toni Abela would not be timid. In one session of this three-year case Alexander Dalli showed up in the court room flanked on both his sides by two uniformed nine-foot giants armed to the teeth, capable as far as I could judge to withstand violent rebellion by outstretching their arms and crushing it in their pneumatic biceps. And that without resorting to the firearms they were carrying. No doubt in that courtroom the prison chief had no reason to be concerned for his safety. But in that moment, he testified without the bother of using words, and in a way none of my witnesses could, to the culture of fear he inflicted in the prison where he was boss.

He was not the boss in this courtroom. Judge Toni Abela was. And the judge kicked out the uniformed gorillas, weapons and all.

I wonder if the judge made a note of that incident which turned up when he was writing that bit in his ruling where Judge Abela breaks into French: time is long gone, he said, where officials could behave on the back of the maxim of je suis le roi, je suis la loi.

Burn.

There was a commenter on one of the news pages who placed two figures he disliked on a weighing scale. On one side the positively revolting Manuel Delia and on the other Alexander Dalli. The commenter found he preferred Colonel Dalli. In my defence as I find myself hauled up and found lighter, on the other side of the scale Alex Dalli is still flanked by those armed giants.

Of course, none of these considerations should be relevant. No judge should be making decisions under the condition of what angry commenters might say about them. Tactics should not come into it. It absolutely should not matter if the plaintiff in this case was someone more known for their gentle touch than I. It should not matter if the government’s job is hard enough without media scrutiny. But if you thought that judges are as free from the conditioning of public perception as they themselves would hope to be, you’d at best be naïve.

The only thing that should matter is right or wrong according to law. Our constitution includes mechanisms to ensure that the power given to the government to fulfil its responsibilities is retrained by limits and safeguards. The state has the power to deny prisoners and detainees the basic freedoms you and I take for granted. But that power cannot and must not amount to inhuman conditions or torture. To prevent that, detainees have rights which lawyers should be able to help them secure.

But sometimes even basic legal safeguards are not enough. Sometimes detainees are prevented from seeing lawyers. Sometimes the conditions in which they are kept are so oppressive and weighed down by intimidation that the only solution they see is setting their beds on fire (as happened in Safi in 2019) or hang themselves from the neck until they die (as happened so many times under Alexander Dalli’s burning watch).

The constitution provides for freedom of speech as the first and last safeguard of people’s basic rights. It presumes that if information flows freely the public’s moral outrage would move governments to restrain themselves. Perhaps that is naïve. But there’s a reason some commenters openly admit they would rather not know what’s happening behind bars. That is an implicit admission that if they find out what’s really happening, they would, despite themselves, be moved to demand their government restrain itself.

When the government prevents journalists from doing their job, or as Judge Abela eloquently put it in his judgement, when the government builds walls between journalists and the public, they are giving themselves the cover of secrecy to abuse their power in some other way.

Perhaps this is romantic, but it’s not meant to be. Judge Toni Abela wasn’t merely taking my side when he recognised that my fundamental rights were violated. He was taking the side of the little woman and the little man forced to despair in the custody of the roi, of that tyrannical bastard who thought prisoners were game.

In balance then and as objectively as I can possibly be in these circumstances, Judge Toni Abela’s decision is an act of heroic judicial courage. He took the side of the little man, and anyone who’s ever seen me knows I don’t mean that as a description of myself. He ranked the protection of prisoners and detainees over the pride of the heaving chest of Alex Dalli.

For legal reasons which he went into and which I struggle to understand Judge Abela relieved Alex Dalli’s political bosses from responsibility in this case by declaring Byron Camilleri unsuited.

Be that as it may the case now goes to Byron Camilleri. What will he do? How will he treat my fresh application filed just yesterday to visit the prisons and the detention centres? Will he comply with the ruling, or will he seek to overturn it?

Three years ago, I won another free speech case I brought against the government. It was over their daily removal of flowers and candles and pictures from Daphne’s protest memorial in front of the court room. That time Robert Abela said that because his government was serious about respecting free speech his government would not appeal that decision.

What will they do about this one? By the same logic, if they are still serious about respecting free speech, they would comply with the court’s decision and not seek to appeal it.

On the day when I find out that they are arguing the law should give them the power to spy on me and my family without having to tell me (for there is no doubt under their definition of journalist I am most definitely one), I feel worse than naïve in daring to be hopeful.