I had the pleasure today to speak at the yearly peace summit called by the Community of Sant’Egidio, that is meeting this year in Madrid and discussing “Peace With No Borders”. I spoke today in a session focusing on “Media and Social Media vis-a-vis the Conflicts”.

Twenty-three months ago today Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed in a car bomb in Malta. It was the first time that a journalist in Malta had been killed.

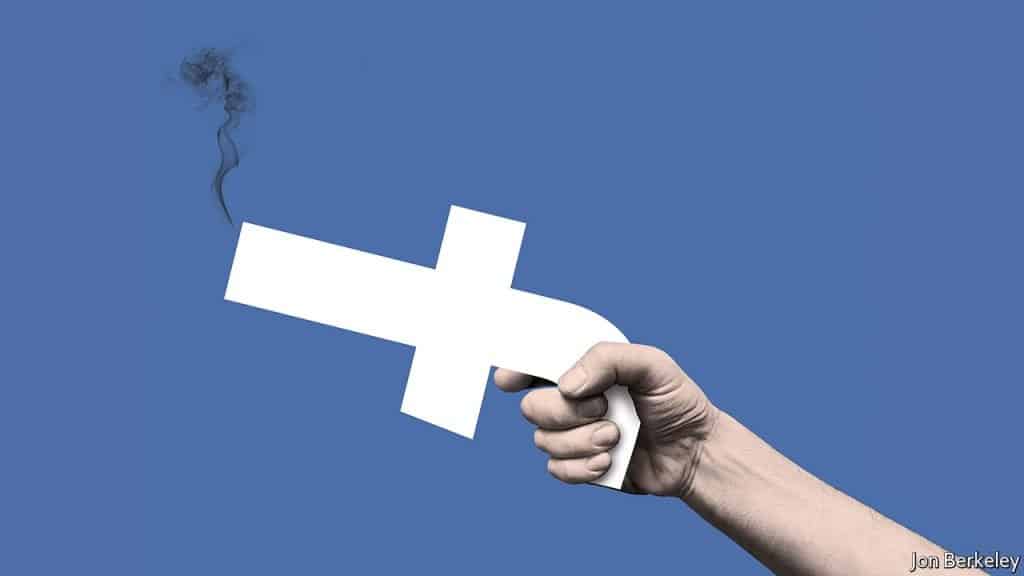

For many around the world who understandably thought of Malta as a place you go for holidays that explosion rang from an unclouded sky. But the conflict that would ultimately claim the life of Malta’s most prominent journalist has been long coming and an important theatre of that conflict was social media, particularly Facebook.

The chasmic polarisation, the virulent language, the pervasive dehumanisation, and the gross misinformation ought not necessarily to have led to fire and violence in the street. But the fact that all that was expected to produce anything less shows that even Maltese people were naive about the political realities of their country. They still are.

Deeply divisive politics did not start with Facebook. We’re speaking in Spain where the blood of civil war is not completely dry. I do not presume to bring you cultural lessons from Malta.

But there are aspects of Malta’s recent history that are, even to me, quite staggering.

Daphne Caruana Galizia has been an outspoken witness of that history.

For most of her career as a journalist, the Labour Party campaigned to prevent Malta from joining the European Union.

She found isolationism and the piracy of cheap cunning of an offshore economy ideologically abhorrent.

And when the generation that used violence to suppress democracy in the 1980s and the generation that campaigned against EU membership up to 2008, passed the helm to the leadership that runs the Labour Party and Malta today, her reasons for pitting herself against that behemoth of Maltese politics became even more urgent and increasingly more frustrated.

To map this landscape you have to set it in the context of the media with which information flowed in the country.

Until 1987 broadcast media was the strict monopoly of the State, one of the treasured legacies of centralised powers that our homegrown masters inherited from the British colonists. In the darkest years of Malta’s democracy, between 1981 and 1987, the very name of the Opposition Leader was banned from the airwaves, a Pharaonic touch to contemporary politics.

The Opposition Nationalist Party sought to beat this monopoly and broadcast its message illegally from Sicily. Anyone appearing on those TV frequencies was banned from returning to the country.

When the Nationalists came to power in 1987 they promoted a turn the other cheek policy in many respects including broadcasting. They opened up broadcasting frequencies to competition and in a gesture, they deemed democratically symbolic but which would prove cataclysmic they gave the first non-state broadcasting license to the Labour Party. Eventually, they gave one to themselves as well.

You may think that concepts such as ‘fake news,’ ‘misinformation’ and ‘alternative facts’ are new fangled. Malta has had 30 years of TV news where reporting is not related to facts but to the convenience of the political party that pays the salaries of the reporters.

Most people — easily four-fifths of the population — still consider local TV news as a primary source of information on what happens in the country. For many of them, it is the sole source of information. They have three TV stations to choose from: one owned by the State and serving the government and one each owned by each of the political parties. You get Pravda, Pravda and Izvestia.

This has allowed audiences to develop a very awkward relationship with the truth. Thirty years of having broadcasters do much worse than put in shades of bias over news-reporting, throwing instead willful misinformation, fear-mongering and slander in the mix have trained people to choose what to believe not according to how credible, evidence-based and substantiated it is but according to what flag the news source is waving.

This has several surprising consequences.

Politics is made of black and white. Any grey, any attempt at a critical and objective evaluation, is immediately and intuitively dismissed as an attempt by the other side to murky the purity of one’s political system of belief. I choose the words system of belief advisedly. Because the attitude bears all the hallmarks of religious fanaticism: the sort of siege paranoia that whips up chanting and flag-waving crowds to hysteria.

It is with those tools that the Labour Party campaigned against EU membership. Mental pictures of body bags and marauding Sicilians were spread about in language we are sadly all too familiar with as the politics of fear have become mainstream in beloved democracies such as the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom.

There was one thing missing in those campaigns: the possibility to personalise fear and adapt it to an individual’s prejudices and automated responses. That is what Facebook brought in.

Few people realised what was going on. Daphne Caruana Galizia did. She uncovered massive corruption and the close relationship between politics and crime.

In 2013, Malta appointed a charming Swiss lawyer — Christian Kaelin — to sell its passports to Russian oligarchs, Saudi oil sheiks, Nigerian bureaucrats and Chinese tycoons.

We would eventually learn that Christian Kaelin worked in close association with Alexander Nix who ran Cambridge Analytica and manipulated big data to condition voting behaviour and used dirty tricks to control the outcomes of election results.

Kaelin and Nix worked together in several Caribbean jurisdictions to secure the election of political parties committed to introducing passport schemes identical to Malta’s.

In spite of the evidence that backs Daphne’s stories up, what she reported was branded by Malta’s prime minister Joseph Muscat as the biggest lie in Malta’s political history. It is then a fiction conjured by a witch. And the witch is dead, burned as witches must be.

How does he get away with it? The atmosphere of alternative realities co-existing in a perpetual state of mutually assured destruction allows thousands of people to substitute in their minds objective truth with more appealing conspiracies.

I am a journalist sharing here in Madrid my experience of what is happening in Malta. But when the Labour Party media get wind of this intervention, this will be presented as an act of treason. I am speaking badly of Malta with foreigners. For a post-colonial island, speaking with outsiders with anything but a picture-postcard visitmalta.com sales spiel is an act of treason.

Targeting women is easier. The post-colonial sensitivity to treachery and collaboration with the foreigner is positively numb compared with the ingrained misogyny of an ingrained macho culture where talking politics is for men and women are for clearing up the beer stains when they’re done.

Daphne Caruana Galizia was caricatured on formal party owned media as a witch: a woman who speaks out of turn and must, therefore, be possessed by the devil. Her warnings about corruption and her revelations of it were reduced to the hysterical haranguing of an unhinged woman gone off her rockers. Like the PN Opposition Leader on State media in the 1980s, her name was banned in the media that resented her and replaced by aphorisms like ‘the Queen of Bile’ or ‘the Witch of Bidnija’, the small village where she lived.

Her journalism became an act of evil, like a mediaeval curse that can only be cured by inquisitorial expiation tied to the stake.

The Labour Party organised armies of online trolls to spread the message. Whatever she wrote, whatever she published, however compelling, would be choked under the slander that it was a fictitious product of hate.

‘Hate’: that word. The charge projected on others by those so deeply seeped in it.

It is the vehicle for fear. It is the acid that dissolves our attachment to our humanity.

That is why when Daphne Caruana Galizia died some people cheered. It is why a protest memorial demanding truth and justice in her name in the middle of Valletta is destroyed at least twice a day, one of those times by government employees on official duty.

It is why in spite of a resolution of the Council of Europe and exhortations from the international community, the government refuses to open a public, independent inquiry into her killing.

It is why official spokesmen of the Prime Minister have denied that a car bombing of a journalist amounts to an assassination and have accused Daphne Caruana Galizia’s sons of matricide and of seeking to hide the truth about their mother’s death because they relish the harm suffered internationally by Malta, the country they are accused of hating.

This happens because the people whose political power depends on pervasive fear and hatred and a wilful detachment from the truth and demonstrable and verifiable facts have tools available to them in conventional and social media that allow them to get away with this.

Carole Cadwalladr, the journalist for The Guardian who worked on the Cambridge Analytica story over the last few years wondered aloud recently whether it is possible to have a free and fair election ever again.

It is a reasonable fear. We’ve seen Daphne Caruana Galizia bombed in Malta and nothing happened to those who killed her and those who ought to have been politically ruined by her revelations. Perhaps these are the same people or in any case, they are closely related.

You’d have to wonder then, in addition to musings about wether we’d ever have free elections again, if journalists who speak truth to power in Europe can ever work without danger of losing their lives ever again.