This is not a review of Mark Montebello’s biography of Dom Mintoff. And the first reason it isn’t is that I haven’t read the book. I know from personal experience that there are many people willing to review my books without bothering to leaf through them, and I know just what sort of disservice that is.

So if you want a review of the book by someone who hasn’t read the damn thing, might I suggest you go to today’s Malta Today where the omniscient Raphael Vassallo provides one.

I will read the book though as soon as I can because I’m interested in what it has to say. A biography of Dom Mintoff, hopefully not one more attempt of many that have been made to draft the case for his canonisation, is a vital contribution to the understanding of 20th century Malta. We can’t just read biographies of people we admire, can we? How would we understand Stalin or Mao if we only read biographies of historical unicorns?

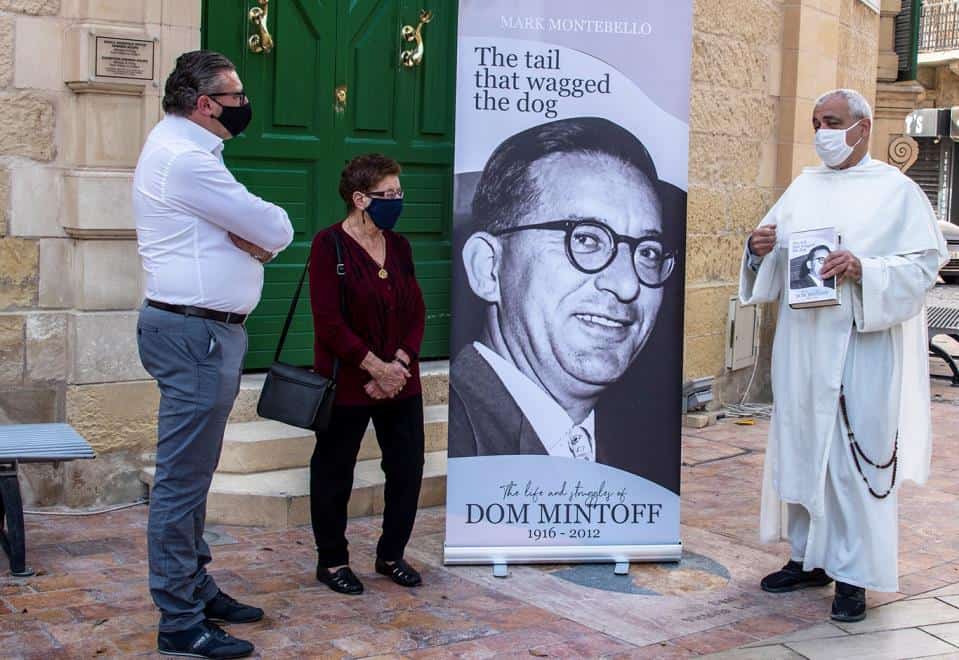

Right now, I’m interested in the incident reported in today’s Times of Malta that says the book has created uproar within the Labour Party and has become some sort of instant taboo. Considering in principle that the book is about the founder of the Labour Party and the extracts from it that have been published in newspapers make no attempt to draft the case for Dom Mintoff’s canonisation, that should not be surprising.

But here’s the rub. The book is a publication of the Labour Party, or in any case, the publishing house owned by the Labour Party called the Sensiela Kotba Soċjalisti.

The promoters of the book rightly expected that to get people to talk about it, they shouldn’t serialise on the Sunday newspapers some esoteric details about Mintoff’s negotiations with Duncan Sandys or crass Parliamentary banter with Ġorġ Borg Olivier. They went instead for the pages with all the sex stuff and how and when Mintoff was denied it in the matrimonial bed and how he compensated with his conquests.

All that’s well and good. But the extracts also spoke about the nature of his relationship with his wife, his daughters, and many of the women in his life, whom he appears to have treated as chattel, possessions, victims he could control and bully.

That’s interesting because it is about the private life of a public person. It is also interesting because it should help us, students of the history of the time, understand the character of the man whose politics was defined by sweaty machismo and incoherent bullying.

There’s a limit to how much insight snippets of private life can give us into the character of a public person. Joseph Stalin drove his wife to suicide pushing her with the same sadistic streak that pushed millions to gulag and death. Adolf Hitler, on the other hand, loved his dog and married his mistress after he decided to kill himself. Hardly a pattern.

And yet, after Dom Mintoff’s daughters denounced the book about their father (or presumably what they had read in Sunday’s papers about what it said of the abuse perpetrated by their father) we’re left asking: it’s all very interesting, but is it true?

The thing with history is that it should not wait for the permission of anyone to be written. For the sake of argument let us assume that Mark Montebello’s research and evidence are sound. Dom Mintoff then did mistreat and beat his wife and bullied his daughters. But his daughters might feel it their duty, or perhaps their interest, or merely their desire, that this truth remains private. For whatever reason, they might prefer it that way.

The memory of Dom Mintoff as their father belongs to them alone. The memory of Dom Mintoff as a public figure belongs to all of us. And if in 1974 Mabel Strickland would have preferred to avoid reporting that the injuries sustained by the prime minister of the time were actually inflicted by the prime minister’s brother because of the woman they appeared to unhappily share, in 2021 we have no such scruples about covering up for politicians.

Assessing whether Mark Montebello’s book is good history then should not depend on what characters in the book (or their relatives) think about the matter. The assessment must rely on the quality of his sources, the reliability of the evidence which he produces, and the soundness of his inferences. As I said, I still need to read it.

Where’s my point?

The author of the book had his work published by a house owned by a political party. That, whether he likes it or not, is not an irrelevant consideration.

The issue of publishers owned by political parties came up recently when Aleks Farrugia was passed over a European Union literature prize for a book SKS published for him. The competition’s guidelines advise jurors to ignore books published by political parties, no matter their merit.

The objection to this rule was that SKS publishes great books. Sometimes, indeed, it does. There’s no doubt about that. But whatever it is that SKS does right, the existence of SKS (and, while it still existed the PN’s PIN) is predicated on the motivations and interests of the Labour Party.

For all I know, SKS’s decision to publish Mark Montebello’s book was brimming with intellectual honesty and a genuine desire to pursue the truth even if that truth challenged the myth of its owner’s founder, even if they helped expose the Labour Party’s greatest historical hero as a person who in today’s politics would never have been able to politically survive.

This could be what happened.

What could also have happened was that the intellectual honesty of the SKS did not go higher up the ranks in the Labour Party. Most of them assumed this would be just another book with a good picture of Dom on the cover that loyal Laburisti would buy just because, and some nice profits would flow in the general direction of the party.

And now the book is stuck in an internal crisis within its publishing house. Instead of reading it to assess its content and the extent to which it contributes to our understanding of our history, we are debating why the Labour Party published it at all, and if they really knew what they were doing when they did it.

Now we’re watching Mintoff apologists and hero-worshippers (and, rather more understandably, Mintoff’s children) putting pressure on the publisher to stop promoting the book.

And here is why it should have been intuitively understood that the EU literature prize excluded books published by political parties. Because the test of the intellectual honesty of parties is not merely in what they decide to publish but in what they publicly regret having published. Ultimately, the owner’s interest, once pinched, will come first. And in an intellectually free democratic society, the effort to define the truth, whether through history, journalism or literature, should not be subjected to the interests of a political party.

In place of the transparent interest of publishers to promote books to as wide an audience as possible, we have the obscure motivations of political parties including, in this case, the grotesque need of preserving their founding myth or the diplomatic desire not to cause offence to the children of their founder.

It is, no doubt, the right of political parties to publish anything they please. But histories, or literature, or science should be free from the motivations of political parties. I will still read Mark Montebello’s book because I’m interested and curious. But the fact that he published it through the party founded by the subject of his research is not a good place to start.