I’m trying my hand at longer podcasts … it will take you 25 minutes to listen to this or, depending on your reading speed, more or less to read it. If you like the format (or you don’t) please say so.

As honest citizens committed to the social responsibility of resisting and rejecting organised crime, it is our duty to be more vigilant on local football now that the most famous Maltese man at a global level, known variously as the Artful Dodger of Europe and the 2019 OCCRP Man of Organised Crime and Corruption, has taken the reins of professional football. I say most famous man, because the more famous and far more worthwhile Maltese people are, thankfully, women.

Like Joseph Muscat I realise there’s far more to football than goals, penalties, victories, and defeats. We must all acquire a crash appreciation of the money side of football, in all its complexities, because it’s about as big an opportunity for money laundering and for mafia crime as capturing a government, without the burden of the obvious public scrutiny of being a prime minister.

Football money flows across borders in huge amounts. Most of the money is paid by and to football clubs and exists outside the oversight of national and international football associations. That fact alone creates the opportunity to move illicit money and wash it in the flushed flow of funds.

The money comes from a multiplicity of sources. Seen as a clean ordinary business someone invests in football because they expect a return on their investment from football’s sources of known profits: TV and media rights, gate money, profits from the player transfer market, and merchandising.

The next circle around this apparently legitimate commercial core is betting, some of it through licensed monopolies, much more through the grey and black areas of illegal betting. Illegal betting may, but does not necessarily, combine with match fixing and bribery and corruption to game the game as it were.

There are two fronts of vulnerability to abuse. The first is that even at the lowest level the moneys involved are considerable and tend to be irrational. I’ll explain what I mean by irrationality further down. The other front is that growth in the economic turnover in football is stratospheric. The two factors combined mean that there’s a lot of room to hide unexplained wealth and money from illicit sources because seeing someone connected with football flush with money does not raise the sort of suspicions in the way that, say, a suddenly rich politician might attract. A 22-year-old footballer in a new big boat is less strange than a 32-year-old minister in the same situation.

Consider also the fact that football is a much-loved community activity with a strong engagement of grassroot support and social cohesion. Football brings money to poorer communities, gives them purpose, turns on a strong sense of shared identity, and promises social development and just-add-water social mobility. The young football player from the sticks or the slums can become a millionaire (or at least reasonably well to do) if spotted in time by talent scouts.

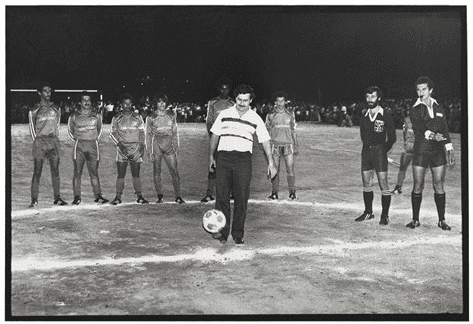

This allows for organised criminals to launder their reputation and to create social alliances that protect them from scrutiny. Pablo Escobar is the classic example of that. He owned a football club and used it to spend money in a poor community representing him as a charitable hero for “his people”. It’s a lot like how they use religion, fund churches and their social community work and participate in popular religious festivities, carrying statues and giving donations like Don Fanucci before Vito Corleone kills him and takes his place at the foot of Christ the Redeemer.

Then there’s something else. The separation between football and politics is zealously guarded by football managers ostensibly to keep the game’s autonomy and independence and the inclusion of everyone whether they’re liked or disliked by the authorities. That’s all well and good. But Sepp Blatter’s exhortations of independence from politics now sound like a scheme to push back on institutional oversight that could stop corruption from football and prevent the use of the game for the laundering of illicit money.

I don’t want to present myself as an expert on the infiltration of crime in football. I have written about the subject before, particularly where suspicious conduct of Maltese clubs was so transparent it even drew my inherently indifferent attention. For example, read pieces I had written about affairs at Mosta FC and the involvement of Darren Debono of oil trafficking fame in the football world.

Now I feel we all must become better informed on how money laundering and crime use football for their illicit ends. The main source of this information I am sharing with you is studies conducted by the FATF who have analysed the reasons the sport is a magnet for crime.

A lot of money passes through a lot of hands: clubs, players, sponsors, media, investors, agents, the government, the tax authorities, and the owners of real estate. Payments are made in multiple forms, grants, loans, employment contracts, through foundations, companies, trusts, as commissions, as professional fees, as interest, as tax deferrals, you name it, it’s used. Money launderers thrive on financial complexity mostly because few understand it better than they do. In the dark and secret caves of financial esoterica they stack money no one is surprised they have but they would be surprised should they ever find out where it came from and where it’s going.

It is relatively easy to enter the football business. It’s obviously not easy to be a footballer, that’s not for everyone. But if you have money to spend or to invest or to hide or to recycle getting into football requires no qualifications, no license, no past experience, no peer acceptance. Anyone can buy a club. Anyone can get in.

Once in, you can be as exposed or as hidden as you like. More importantly your financial transactions are assimilated in the complex network of stakeholders and the arcane layering that comes with the business.

More importantly the nature of the business and the rapid rate of growth it is susceptible to means that often clubs are poorly managed by semi-professional or barely competent people. This is especially true of Maltese clubs.

This is not meant as a broad-brush criticism of people manning the fort in football clubs. Almost all of them are in it for the love of the game, and the club. Many expect no reward except what they must surely consider as prestige and the thrill of winning. But almost none of them can afford to give full-time attention to the club’s business and nearly none of them have had any formal training in business management, let alone detection of crime and identification of money laundering. For them, money is money, especially given that most of the time there’s so little of it. They will not ask God for the workings of his miracles, and they will not ask a donor or an investor for the provenance of their generosity.

That’s another thing to keep in mind. Before a saviour comes down to rescue a club from the doldrums or from languishing in a semi-permanent relegation crisis, football clubs are nearly always cash starved. Clubs may have a hall full of glass cabinets brimming with trophies testifying to a rich and glorious past. But they’re ever as likely to be poor at present and uncertain about their tomorrow.

When you see the portraits of football club presidents painted on oversized flags and banners, when you see them raised above shoulders, and spoken of in ways that would be embarrassing for war heroes or Nobel laureates, you’re not seeing an audience that is likely to make a critical assessment of the provenance of the wealth of their patrons.

The diversity of legal structures used for the business in practice prevents the application of any meaningful standards for financial propriety and rules of transparency. Trusts, companies, publicly listed firms, foundations, partnerships, associations, voluntary organisations: these are all models with their own legal and financial framework providing multiple opportunities to make bad money feel welcome.

There’s also an issue of scale. We’re talking big money, sometimes stupid money. We have nothing in this country of the scale of Juventus or Manchester United, businesses that turnover budgets as large as cities and some small countries. Yet running a club on the winning side of Malta’s premier league is no child’s play. The money is considerable.

And the expenditure is irrational, which is a consideration I hinted at earlier. Sustainable businesses thrive on reasonable risk. Reasonableness is a factor of predictability, of honing all controllable variables allowing one to identify those factors beyond one’s control, the elements of acceptable risk. That will allow for business planning, projecting spending and the return one can reasonably expect from that spend or what cost must go into covering bases in case something goes wrong. Consider insurance: it is a business built on things going wrong, but it is successful because it can rationally predict what is likely to go wrong and what is likely to be fine.

Football is not like that. People charge crazy money for their services which they can fail to deliver because of a twisted ankle or a bad mood. I’m obviously over-simplifying things here. I do not propose to provide a business manual for a football manager. God knows there are people with a lifetime of experience that can provide that.

The point I am trying to make is that the nature of this specific business allows strange amounts of money to pass hands without what you and I would consider rhyme and reason. If you used a car wash business to launder your money like Walter and Skyler White did, it’s going to be difficult to tell the tax-man that you had a bumper month where you washed 10,000 cars when at full capacity your facility cannot handle more than 20 cars a day. But who’s going to argue with you if your football club claims it has spent an unscheduled million euro on buying a 14-year-old kid from the projects of Marseilles?

Speaking of that 14-year-old kid from the projects of Marseilles, or for that matter the boy who did so well playing for one of the nurseries like Valletta or Birkirkara or similar, there’s also the vulnerability of minors, possibly from poorer social backgrounds, exploited and trapped in generously paid contracts, never realising they are being used by criminals to launder their money. The minors are represented only by their parents, quite likely relatively incompetent in financial matters, possibly starved for money, and understandably blinded by the unbounded pride of a parent in their child.

A rags to riches story, sheer talent and skill overcoming the ugliness of economic and social disadvantage, are just what makes football the disproportionate object of such passion and global admiration. There’s no elitism in football as some other public-school sports might have. The game bridges racial divides, except when it doesn’t. In and of itself, or at least as a rallying cry when the bad behaviour of thugs and hooligans mars it, football is “the beautiful game”. Under that surface sheen is a paradise for money launderers. Law enforcement is careful, politics is scared, public scrutiny is distracted, all-star struck by the glamour of the sport. It is the business equivalent of a coconut tax haven.

And the beauty of the game pays greater rewards than just as a vehicle for money laundering and handsome legitimate returns on illicit investments. It pays criminals with prestige, showers them in glory. No one who has just won the village, the town, the city a trophy can in the eyes of the fans do wrong.

The FATF has documented several ways criminals use football for their wrongful ends, and they keep finding new ways all the time.

French investigators found a businessman who was a president of an amateur football club using his privately owned companies to donate money at the end of every season to cover the losses incurred by the club. To hide the source of the money he held back on filing the accounts of his companies, covering up the fact that he was stripping his businesses to dodge tax.

Belgian investigators found a football club nearing bankruptcy solicited funds from an overseas investor with zero experience in football but with a compelling rescue plan and the means to retain the near-dead club in existence. It turned out the investor was the subject of investigations for fraud.

Mexican investigators looked into the reasons why a young businessman who had little money a few years earlier, bought a third division club with no prospects and spent large amounts of money in a new stadium, facilities and buying good players. Rapid promotion for the club was secured but investigators couldn’t understand what he was getting out of it except for becoming known for something he hadn’t been: a successful sports entrepreneur. Eventually investigators found the club president was a drug lord and the football was the way he could be seen using the luxury he acquired from drug money.

Also in Mexico investigators found a businessman bought a football club to gain access to local politicians, inviting them to games and parties and letting them glow in the glory of the city’s football club. His new friendships and access to politicians helped him win construction and infrastructure contracts which is where he made his real money.

Closer to home and rather famously, in 2016, the Casalesi clan of the Camorra, attempted to use proceeds from their criminal activities to buy Lazio FC.

Argentinian investigators found money being laundered in the football player transfer market. Anonymous investors approached cash strapped clubs offering to help finance their debts. They did so by buying for them football players from outside the country using funds hidden in tax havens. The money never actually passed through the club or even any bank in the club’s country so no one is any wiser. Taxes are dodged and money is washed while clubs are inexplicably richer.

French investigators found an unlicensed player agent profited from backhanders paid by an operation in Eastern Europe closely associated with organised crime. The payments covered bribery and corruption and were kept under the radar using a licensed middleman based in another country. Belgian investigators, meanwhile, discovered a European bank account held by an unlicensed agent used to transfer payments for players illegally trafficked from Africa. They found a football coach had power of attorney over the bank account pocketing money made from human trafficking masquerading as football transfers.

Belgian investigators also found lawyers and club bosses used their powers of attorney to deposit multiple bribes to fix matches. The structure was also used to transfer payments for doping purchased illegally for football players.

Interpol has led complex operations in Asia to catch people betting on fixed matches in relatively minor leagues in Europe. Belgian investigators found people from the footballing world – players and managers – were buying casino chips on online casinos in inordinate amounts, betting on matches they were fixing themselves.

In the UK, investigators found a player’s salary informally incorporated his agent’s fee so that the agent could dodge tax.

The FATF also identified other ways to launder money using football. Take a rich investor who buys a football club and finances the purchasing of new players. The payments for players comes from off-shore accounts incorporating within the agency fees paid to the selling club, kickbacks paid off-shore back to the buyer. The kickbacks allow the investor to recover their investment while their new asset (the club) gains value giving them clean profit from a hidden illicit activity for zero cost.

An investor might also buy a club doing poorly and “invest” in new facilities purchased for inflated prices from businesses owned by the investor as well. The profits are moved off-shore while cash intakes from the growing football business are also inflated with revenue from other illegal businesses owned by the investor. A win-win-win situation and none of it involves a referee’s whistle.

Any of these activities could very well be already in the portfolio of Maltese football clubs. There certainly are warning signs: cash starved clubs, rapid flash-in-the-pan capital investments, awkward but visible access to politicians, hero-status presidents the wealth of some of whom never fully explained, trafficked football players from poor countries, cowboy agents, some of whom with known associations with organised crime, irrational expenditure, and the exploitation of young football players from poor backgrounds.

These are warning signs, mind you, not evidence of wrongdoing. They fit well with the other reality that makes football a comfortable place to hide dirty money. Politicians, law enforcement officials, the press, and the public don’t ask too many questions from the football world.

The choice of Joseph Muscat to head the association of premier league football club owners cannot be separated from this context. Seven club presidents voted for him and 7 didn’t. It would be unfair to assume that all the 7 who were for Muscat are in football with criminal intent and supported hiring Muscat to pursue those ends. As it would be naive to assume that the 7 who did not support him may never have had anything to hide.

Identifying signs of crime is not a useful tool to make psychological appraisals or to reach water-tight conclusions on what people might have wished or might wish to do.

There are, however, some eminently reasonable conclusions that can be drawn from this development.

All the warning signs of how football could have been and could be used for money laundering and crime now gain an altogether more alarming significance. Seeing photos of Joe Portelli hugging politicians wearing the colours of his football clubs must become more worrying than it ever has. As of course his quasi-saintlike reputation in the towns where he scores football penalties and carries religious statues in public processions. Not to mention the strange acquisitions of (this is not a figure of speech) paradise islands as if he actually wants to look like a Bond villain.

Personalising it on Joe Portelli is not meant to relieve the other clubs from scrutiny. But Portelli is practically a cartoonish archetype of the money laundering front: inexplicably wealthy, generous in his program of developing social alliances, with politicians rattling in his pockets like nickels and dimes. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Portelli ignored my questions put to him directly on whether he was actually paying Joseph Muscat behind the other clubs’ backs for his new role in this position.

And then there’s Joseph Muscat. He expects, because few have the sort of sense of entitlement that he has, to be cleansed by the nobility of the beautiful game and adored by the clubs – the 7 who supported him and the 7 who didn’t – with irrepressible gratitude for the money from God knows where he has lined up for them. He didn’t mind organising the purchase of 3 public hospitals with money coming from off-shore funds with hidden ownership. He is going to quibble even less when using that sort of secrecy to bring money to football, for all the reasons listed above. Who’s going to ask questions?

Above all else Joseph Muscat comes with a deeply rooted penetration in massive social support and loyalty already wrapped in the package. On his own he is bigger in terms of public support and engagement than any of the clubs, probably even bigger than all the clubs put together.

His corrupt years in government have allowed him to invest tax-payers’ money in the eternal gratitude of tens of thousands of people for whom he can do no wrong. He commands a loyal base of public protection and intimidation that keeps law enforcement off his back. Pablo Escobar did not manage quite that sort of support after all the money he spent in his football foray, let alone the sort of capital Joseph Muscat enjoys on his first day of business in football. He doesn’t need to buy his way into safety. He enjoys it already.

You could say he’s doing this to consolidate his safety given that inevitably, as Robert Abela strived to take the Labour Party away from him, Joseph Muscat’s aura of infallibility started being eroded. He is now putting a stop to that backslide.

One football club president who supported Joseph Muscat’s nomination told his colleagues the disgraced former prime minister was “exactly what Maltese football needs at this time”. Muscat and football hope to thrive on the back of each other. Given the experience of both sides, they can make a safe bet that in the big scheme of things crime pays and while everyone is celebrating victory in a match or a league, fixed or fair, no one is going to ask who the victims are and what sand is being stained by their blood.

We are expected to be indifferent to all this. It comes natural not to care about the ups and downs of where Santa Luċija and Mosta and Ħamrun and Mġarr rank in the football league. What might surprise you is that sometimes the people who own those clubs don’t care either. They’re in it for something else altogether. And if you want to live free of the grasp of organised crime, you may have to start caring and find out why they do it.

Why Joseph Muscat does it.