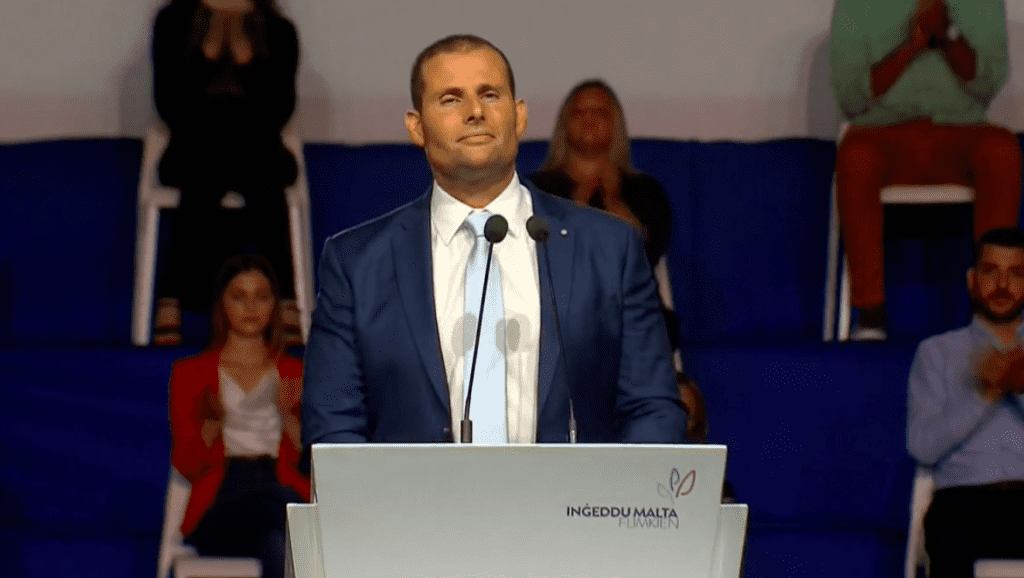

After days of ignoring calls for consultation, Robert Abela appears to have recognised it is of no benefit to him to be seen to rush through so-called reforms to protect journalists without ever speaking to journalists about it. The institute of journalists, IĠM, has secured a reprieve, a postponement of the adoption of the flimsy laws prepared by the government until after consultation happens.

Significantly the government did not agree to conduct the consultations itself. It has instead asked the so-called group of experts to conduct the consultation themselves. They’re the same so-called experts who have already sent Robert Abela a report on the current draft of the law which he proceeded to substantially ignore. Robert Abela told them that if they feel the need to – if? – they could then send him another report.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s good that we’re no longer smelling the blood on the blade hanging over our necks. We have some weeks in which we can continue to make our point: that proper reforms to protect the press need to make a material difference to the present reality and that, by definition, means imposing restraints on the conduct of the government which it currently does not have.

What’s the point of recognising a fourth pillar of democracy, if the impact of its existence is not perceptible to the other pillars? And let’s be frank: the only pillar that matters here is the government, the executive. It is them that a free press is meant to keep in check. If the press is not empowered and protected when fulfilling its duty of being inconvenient to the government, what manner of pillar of democracy would it be?

We’ll use this time as best we can. But the questions remain. Will the government treat this new hypothetical report of the group of experts differently from the way it treated the first one? Will it adopt recommendations that restrain it or force it to act in the interests of democracy and free speech before the interests of its popularity and chances of re-election?

And how will the group of experts conduct themselves?

This too is an important question, especially now that they’ve been lumped with the government’s responsibility of consulting the public. It is also an important question because the conduct of the government-appointed committee has been questionable thus far.

They have operated in a closed-shop, agreeing, behind everyone’s back, to keep their thoughts to themselves and pushing back on all manner of requests for transparency. Imagine that. A committee meant to empower journalists to ensure transparency in the conduct of government, acting in secret behind an opaque wall of something oddly and anachronistically described as a “gentlemen’s agreement”.

Just as journalists were complaining of zero consultation in the preparation of the laws that are supposed to protect them, some journalists received a questionnaire sent out, it seems, by the government-appointed committee.

There were a number of disturbing things about the questionnaire quite apart from the poverty of its structure and design, replete with leading questions, limiting options of replies, and logical tests that by accident or design appear to force inconclusive outcomes or, worse, outcomes the authors of the questionnaire appear to have already decided upon.

For starters the questionnaire was sent only to people whom the government’s Department of Information considers as journalists. Which means I didn’t get it. Not that my opinion matters. That’s not the point I’m making. I’m making the point that the methodology of the questionnaire itself departs from the erroneous premise that a government gets to decide who is and who isn’t a journalist.

Court decisions in Strasbourg and in Malta have already ruled that a definition of a journalist, if it is necessary to have one, cannot be limited to the pleasure of a government. And yet the group of so-called experts in the protection of journalists have implicitly disqualified a few people you might, and I might, and the courts would, consider as journalists from eligibility to that protection.

Then there are questions that are problematic merely for having been asked. Consider the question on whether respondents think journalists should be regulated by a supervisory authority. I mean, sorry, what? How is that a good idea for anyone except for those who want to impose new limits restraining the freedom of journalists to write what they think they should write?

You’d say that was just a question and the respondents, if they’re in their right mind, would answer they disagreed and that would be that.

Except I don’t know who got this questionnaire. I know I didn’t. Did 50 employees at One Productions receive it? Not just the self-described reporters that work for the Labour Party, but also its camerapersons, its sound engineers, and its beadles.

And how about 100 employees at TVM?

Even though the questionnaire is filled out anonymously most of those people would perceive their interests converging better with the interests of the ruling party in government than they would with the public’s right to be informed. After all their ‘reporting’ reflects precisely that ethos of government first, fuck the public.

Even if it were possible that one of those One TV employees might stumble on a deeply buried and thickly veiled loyalty to the public interest somewhere in the deep recesses of their conscience, would they risk using this opportunity to go against the flow?

Consider the questionnaire was sent on a Google Form. Certainly, the people sending the questionnaire can opt out of finding out the identity of the person filling out the questionnaire response. But that means they can just as well opt in. Even if one trusts the members of the government-appointed committee not to want and not to need to know who answered in what way, can we really trust the Department of Information with the same level of confidence?

Even ignoring the fact that there are technological ways that can give this information, the nature of the questions themselves, many of them seemingly irrelevant to the purpose of the questionnaire, appear designed to determine the identity of the respondent.

They ask you what company you work for, your age, your gender, your rank. This is not a survey in the US army. It’s the Maltese press corps. There aren’t that many of us. Once you answer the questions on where you work, how old you are, what bits you were born with, and what the nature of your job is there will be only one name in the world that answers that description, yours.

Imagine then how comfortable would a mid-ranking reporter working for the Independent, say, be answering questions about their perception of the financial stability of their employer in a questionnaire commissioned by a committee that includes the owner of Malta Today.

You see, it is all well and good that we now have time for consultation. We can, then, move on to the next item on the agenda which is to understand and agree how this consultation is being held.

And who with?

Don’t for a minute think that I am making a case for my own participation because I float in that liminal space between the government’s definition of a journalist which excludes me and my own definition, at least, which feels differently about the matter.

The point is that the freedom of journalists to work is a right that belongs to every citizen because it is they who have a right to be informed in order to fulfil their functions as responsible and participating citizens of a democracy.

I know the question on whether the press should be regulated and supervised by some government-appointed monster is not foremost on most people’s mind. It is, admittedly, not foremost on most journalists’ minds either because it is only when shit hits the fan that most people begin to smell it.

But given the right opportunity most people who might prove willing to participate in a national discussion on how their right to be informed is to be preserved, might also be open to the arguments on why having a governing regulatory body clipping the wings of journalists is not such a great idea.

The public have a right to be consulted. And they have a right to be informed of the implications of the questions they are being asked.

I hope, sincerely, that as they decide to take on this job, the government-appointed committee, understand fully their obligations if they are to conduct this process in the manner it deserves. The government has dumped on them its duty of care for people’s fundamental rights. They are being invited to give their views, after consulting widely, on playing with the country’s constitution. Experts, proper ones, have described the current draft constitutional changes variously as ‘useless’ in the most optimistic of reactions, to downright ‘fascist’ in darker, perhaps more outspoken, reviews.

Either they’re going to lead a process that makes things better than they are now or than they were on the eve of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s execution for being a journalist while female, or they should not drink from this poisoned chalice at all.