The story of the fired Valletta parish priest and the church paraphernalia put up for sale in an antique shop opens questions quite beyond the obvious intrigue of a cleric fallen from grace.

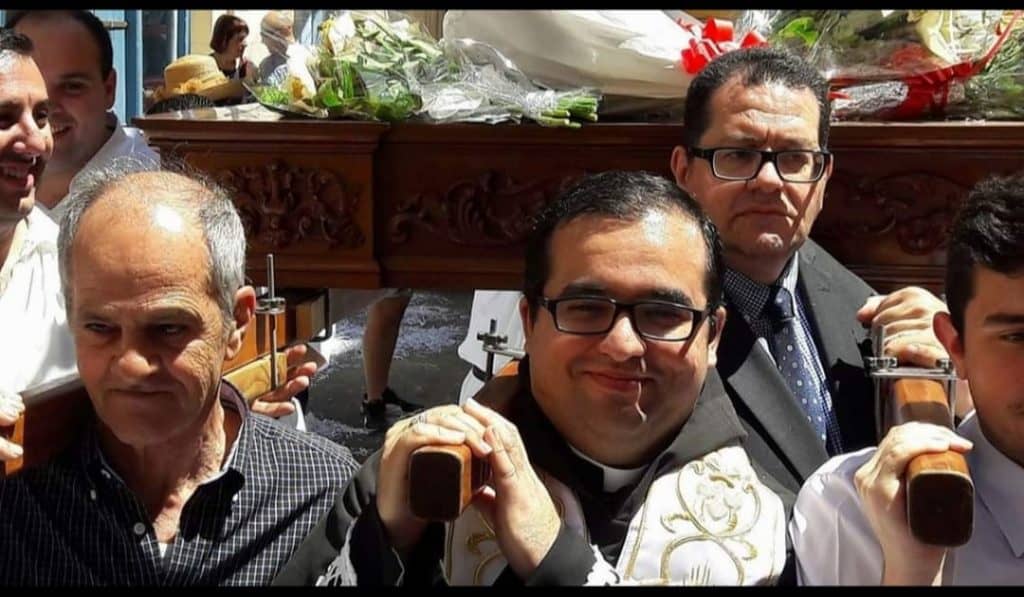

On one level silverware and art that did not belong to Deo Debono but were entrusted in his care found their way to a shop. The priest admitted he was the one to sell them and was fired from his job. It is also a police matter and the police has been sending out signals that it intends to charge Deo Debono, presumably with theft.

On another level there’s a reluctance to find fault with the actions of a priest. Comparisons with Robin Hood have been made giving Deo Debono the status of some sort of folk hero. What does the church need with silver and art? Some have suggested that since he may not have pocketed the proceeds from the sale of the goods his motives must be holy or in any case till now misunderstood.

The debate is understandable. Deo Debono was popular with his parishioners. The St Augustine parish is small and largely inhabited by lonely people. Their annual festa was a timid insignificance compared with the grandiose celebrations of the other Valletta parishes of St Paul, St Dominic and the Carmelites. Deo Debono changed all that.

He was made parish priest around 5 years ago originally appointed for 3 years and his appointment was renewed upon its first expiry. He is nominally appointed by the archbishop but in reality he ruled with autonomy from the diocese. That’s because Deo Debono ran one of 16 parishes in Malta that are administered by religious orders that are distinct from the business of the archbishop’s curia.

This piece of administrative arcana is relevant to get an understanding of what happened in Valletta.

There are 70 parishes in the archdiocese of Malta of which 16 are run by friars of various orders: Franciscans, Carmelites, Dominicans and so on. The Augustinians have a number of convents around the island by they only run one parish: St Augustine’s in Valletta.

That parish is attached to a convent. The community that lives there, most of them elderly friars, are supervised by a prior. The business of running a parish, however requires someone with more energy and Deo Debono (now aged 36) was nominated by his order for the Archbishop’s approval to run their Valletta parish.

Parishes are certainly loci of spiritual life. But they’re also business centres. They collect and spend money and they are therefore run on strict administrative rules to ensure they are efficient and that the faithful’s money is spent wisely.

I spoke with Michael Pace Ross who is the de facto chief executive of the archdiocese. He told me parish priests provide monthly reports on income and expenditure which are monitored against 3-year rolling budgets. They also administer assets which are listed in inventories and periodically checked.

Any substantial expense made by the parish priest needs to be cleared by head office first. And selling assets – say paintings, silverware and property – is unlikely to be approved. The church does not consider its parishes as ‘owners’ of the assets they take care of, merely ‘custodians’. A church painting is simply not theirs to sell.

These curia rules only extend as far as the parishes run by diocesan priests. The 16 parishes run by religious orders are outside the archbishop’s remit. They do not need the curia’s approval for the money they spend and they set up their own internal controls to determine what is a reasonable or unreasonable expense.

Things appear to have got out of hand in the Augustinian’s Valletta parish. Deo Debono set out to transform the timid yearly feast into a festival that could match the traditional festivities of the Paulites and the Dominicans.

He overdid things in the process.

Consider for example that reports from the parish say that he booked 14 bands for the week-long St Augustine feast that was scheduled for the week of his police interrogation. That’s a lot, considering that the parish has a population of less than 1,700. Compare that with the St Helen feast in Birkirkara, one of the largest feasts on the island in a parish with a 10,000 strong population where 8 bands were booked this year.

That alone doesn’t give the full picture. The cost of the street parties around the feast of St Helen is shared between the parish and two major band clubs each with their own resources and fund-raising capabilities.

Valletta’s band clubs on the other hand are attached with other feasts. The cost of all the St Augustine events must be borne by the parish alone.

Apart from the cost of bands, Deo Debono has been ordering street decorations and fireworks like there’s no tomorrow.

Debts mounted but no one in the Augustinian order appears to have been asking where all the money for all the partying was coming from.

Deo Debono’s relationship with his ‘brothers’ in the Augustinian community has not been an easy one. I have spoken to sources familiar with the community who told me there “certainly were tensions with regards to his management of the parish. He isn’t much of a team player and he can be quite arrogant and rude about others”.

However, the community recognised that his work in the parish made him popular with his section of Valletta. “Prior to his arrival, the parish was a quiet one with an ageing population. In a matter of years, some things changed. For example, he came up with an elaborate programme for the feast. How he paid for such a feast remains a mystery – some sections of the media reported that he ran up huge debts in order to finance it. However, he also managed to attract a group of very dedicated youths who worked for the benefit of the parish. This was something which was very much liked by the parishioners”.

This explains the ‘Robin Hood’ notions enhanced by his closeness to Valletta politicians and election candidates, particularly Parliamentary Secretary Deo Debattista and MP Glen Bedingfield.

Though the friars living in the Valletta convent have been worried for some time it does not appear that they immediately connected Deo Debono’s profligacy with things they were missing from their convent.

Last January the convent’s prior realised some paintings were missing. He was alerted by one of the more observant and older members of the community. The paintings used to hang on the third floor of the convent which is an area reserved for the friars. The only persons with access to the floor were the friars themselves and employees engaged to service the convent. These employees are given access to the area by the friars themselves.

All meeting rooms and public areas are at lower levels.

An informed source told me that “at the moment there is a huge restoration project going on and, at the time the paintings went missing, there were no CCTV cameras”. The source commented that “this may seem like an oversight but realistically speaking you never assume that a member of your family is going to steal your stuff”.

“CCTV cameras have now been installed everywhere. From what I could gather,” said the source, “some paintings were moved around in order to try and disguise the fact that the originals were stolen. This was how the theft was noticed. It was obvious from the start that the person who took the paintings knew exactly the value of such paintings”.

Former friends of Deo Debono told me that prior to his arrest he had told them of the missing paintings and said he suspected workmen working on the restoration had stolen them.

A Malta Today report by Kurt Sansone refers to these paintings and says that the “paintings were found in a house known to Debono.” Sources told this website that some of the paintings were found at the home of Deo Debono’s parents.

The police were asked to intervene by the mother superior of the Augustinian nuns’ convent in Valletta who reported she was missing a silver thurible and incense boat. She filed the report after a person – whose identity is not known to this website – recognised the matching set in the shop window of an antique’s shop in Birkirkara.

These are not the thurible and incense boat from the specific case but are shown here for illustrative purposes.

The set was prominently displayed in the “Maltese Antiquarian” shop and put on sale for €3,500.

Through the records of the shop the police found that the thurible and incense boat were sold to the shop by Deo Debono.

This website spoke to customers of the “Maltese Antiquarian” which recognise it as a highly sought-after supplier of antique ecclesiastical items. These customers told me that the shop habitually acquires its ecclesiastical items from overseas and will only acquire locally sourced items if they are sold to them by clerics or people who can prove they have inherited the items from some deceased relative of the cloth.

As parish priest of a church Deo Debono will have appeared to anyone as a legitimate source of the items being sold.

Though the thurible and the incense boat were ‘procured’ from the nuns’ convent, the parish priest had authorised access to it because the spiritual needs of the nuns are served by their brother Augustinian friars. The Augustinian nuns live a cloistered life which means the priests have to come to them to say mass.

The uniqueness of the silver items and the recording of the provenance at the antique shop that was selling them meant Deo Debono could not escape responsibility. Up to that point he had tried to suggest someone else could have been involved but confronted by the evidence there was nowhere to hide anymore.

This website is informed Archbishop Charles Scicluna decided to dismiss Deo Debono from the office of parish priest immediately but preferred to wait out a week before formally announcing it to avoid spoiling the St Augustine feast for parishioners scheduled for last Sunday.

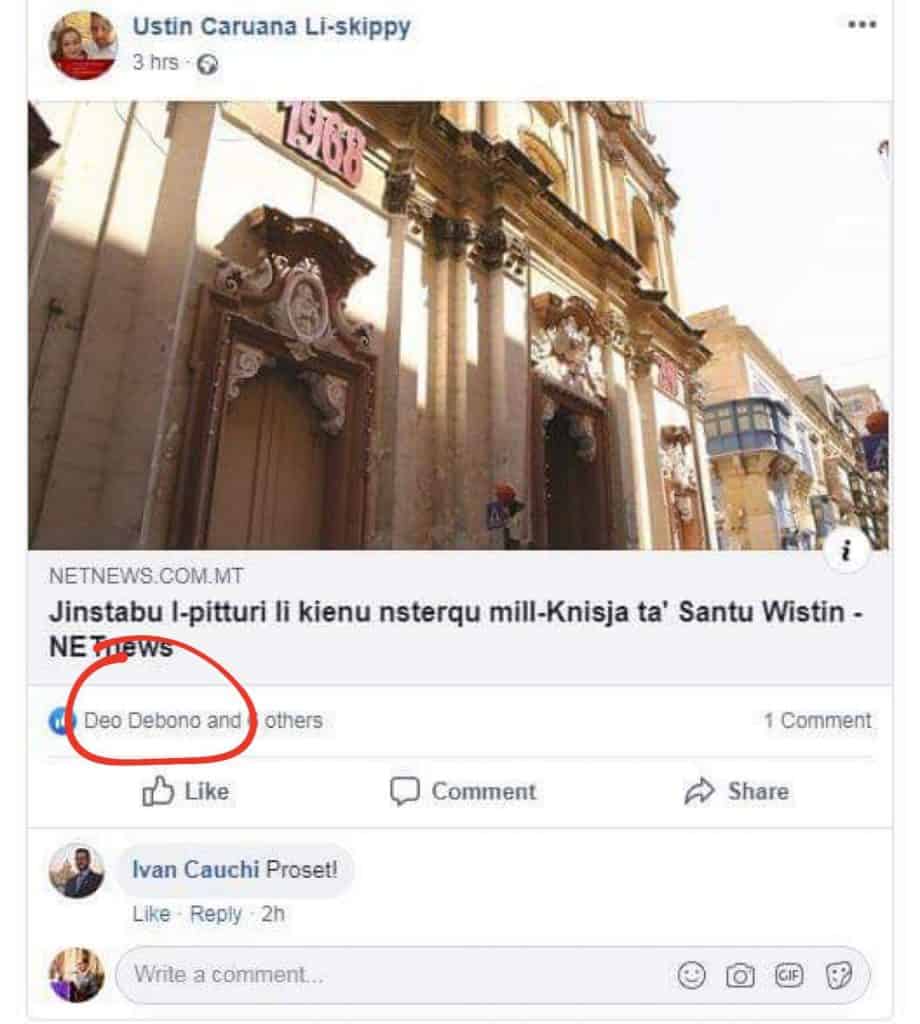

In this period of short reprieve Deo Debono proceeded as if nothing was amiss. His Facebook posts show he was at least putting up a front of serenity. Quite incredibly he ‘liked’ a post on Facebook reporting that the police had found an unnamed suspect responsible for the missing items.

News ultimately leaked and the dismissal of Deo Debono swiftly followed. Police sources told other news media they expected to arraign Deo Debono charged with theft though there appears to be an internal discussion about whether the unauthorised disposal of the property of the convent is actually a police matter or a purely internal disciplinary matter. Can Deo Debono be charged with stealing what he was effectively entrusted to take care of?

By dismissing Deo Debono from the job of parish priest, Archbishop Charles Scicluna has intervened as far as he’s allowed in this case. It is now for the Augustinian order to see what to do with him.

My sources close to the order tell me that the order’s provincial has “asked him not to celebrate Mass in public for the time being. The challenge of course is to discipline the person without forgetting the Christian injunction to be merciful. It is remarkable that despite the hurt and the embarrassment he has caused, the province still prays for him. After justice is served, it would be likely that he spends some time abroad, using the time as a period of penance and reflection. If he still lives in the convent, day to day discipline would be in the hands of the prior although something of this magnitude needs to be dealt with by the provincial and the curia of the order in Rome.”

How to discipline Deo Debono is not the biggest problem the Augustinian order is left with from this mess. The parish’s debtors knocking on the Archbishop’s curia’s door are being told the Archbishop is not responsible for the financial commitments made by Deo Debono. Instead they are being sent with their complaints to the Augustinian order. Someone will have to pay the bills.

A source commented that “it is rather sad to think that the province has to face this. They are fundamentally good people who are trying to live out their calling. In terms of Augustinian religious life, the betrayal is two-fold. St Augustine places a huge emphasis on community life, so much so that the first instruction in his short rule is that the community should live harmoniously in a house ‘intent upon God in oneness of mind and heart’. His second instruction is to ‘call nothing your own, but let everything be yours in common’.

“Evidently, Fr Deo must have missed the memo.”