The facts are those. He was not beaten by the cops. His body wasn’t thrown off a plane by the military. He was not made an example of. I say this because I read comments around recently that point out that things could be so much worse. We could be living in a dictatorship, and this isn’t one. Which is nice.

Our expectations are not of living in a dictatorship. We should not need to feel we must be grateful when we are not tortured or killed. Our expectations are of living in a democracy. And detaining someone for telling Parliamentarians from a safe distance that you expect justice for your friend killed by a collapsed building and quite likely as a result of some form of negligence by authorities that could have prevented his death does not meet the standards of any democracy I am entitled to expect.

Democracy requires our MPs to be kept safe. I’m not saying the police should not have followed closely what was going on or that they shouldn’t have spoken to the protester to assess his intentions and his state of mind. But while he is doing nothing illegal and there is no reason to believe that he will, stopping him and taking him away is in and of itself an intrusion in and a violation of his fundamental right to express himself.

Ensuring the safety of Parliamentarians is a duty of the state. Protecting them from a slogan that criticises their policies or exposes their negligence is not. Quite the contrary the duty of the state is to protect the protester and make sure they have the means to make their protest effective, as well as lawful and peaceful.

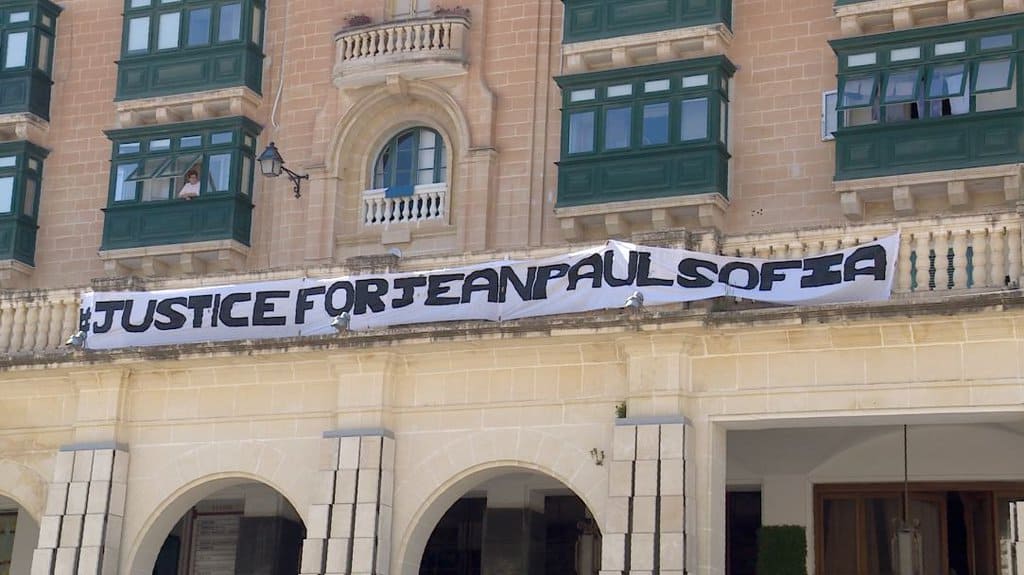

We’ve been through this before, of course. It’s all very familiar. Every banner that asked for Justice for Daphne was struck down by the police. Flowers and candles were dumped until the court intervened to protect protesters from the authorities.

There are many similarities between the two sets of circumstances. In one case, the victim was a journalist killed for her work and in the other case, the victim was a labourer killed at his place of work. At first glance, the circumstances couldn’t be more different. And yet, in both cases, the government insisted that it wanted justice but that it would only allow it to be sought in the criminal courts. In both cases, there was from the start suspicion of some sort of state responsibility whether out of negligence or outright complicity. In both cases, the government’s repeated refusals increased the suspicion and consequently increased the desire and the need for an independent inquiry.

When protesters demanded justice for Daphne, the government targeted them as it still does and accused them of partisanship and of acting out of hatred for the Labour Party. They used the fact that Daphne was a universally known critic of the Labour Party as evidence of that. Robert Abela went as far as accusing Daphne’s children of being more interested in “harming Malta” (which for him and for his colleagues is indistinguishable from the Labour Party) than they are desirous of justice for their mother. They built on the accumulated hatred against Daphne mobilised during her life, to denounce campaigners looking for justice after her death.

There’s no such background on which the Labour government can discredit Jean Paul Sofia’s mother, his friends, and supporters of their cause for justice for their lost loved one. For most people he was unknown before he died. Nothing he ever said could be twisted to mean that he wished Labour’s children to die of cancer. Nothing he ever said could make him look like a “gossip”, to use Alfred Sant’s recent description of Daphne, which apparently earns the gossip the death penalty.

Jean Paul Sofia is just a man whose life has been cut short. It was a life he had a right to live, not because he was special in any way (though like any mother, his mother would disagree) but simply because he was a human and in this civic religion called citizenship every human has a right to live.

We know accidents happen and sometimes there’s nothing that could be done to prevent an accidental death. But sometimes some things could be done and are not and public independent inquiries serve the purpose of looking into the might-have-been so that those lessons become the will-not-happen-again.

For a while there the Daphne Caruana Galizia inquiry looked like it might prove a success story. It looked like having reached its lowest point by allowing her to be killed, this country would reach a high point of finding a way of learning from its deadly errors.

But the way the government has behaved since that inquiry was concluded – ignoring its recommendations, mocking those who insist they are implemented – shows that this is a country that does the wrong thing because it wants to and then does the wrong thing again by covering it up.

You see, for the government, it does not matter if the victim of its actions is a “political enemy” or an anonymous private citizen. It doesn’t matter if you’re blown up in your car by assassins or a roof collapse over your head because of cowboys building incompetently. Either way the government refuses to carry any consequences for its failures or complicity with crimes that cause the collateral loss of life of innocent bystanders.

Perhaps this might be the lesson we all need to learn. When Daphne was killed people could comfort themselves in thinking that the government’s behaviour was of no risk to them. They’d never do what she did. They would never stand in the way of the government because they have no interest or desire to do so.

The hooded friend of Jean Paul Sofia was never a “ħabib t’Austin Gatt”. He probably never lived in Zimbabwe. He never messed up the bus routes as people believe I have. He never had any of the things people believe motivate me to unfurl banners in protest of the government. He never had any interest or any history in politics. And yet he was arrested because he asked for justice for his friend.

Perhaps now people might realise that this could, without them ever having done anything to provoke it, happen to them.

If you’re not the one buried under the rubble, you might be the one asking that something is done about the death of your friend, your mother, your son, or someone you never knew alive but whose untimely death has moved you to speak out. And then, as if you’ve done something wrong, you’ll be sitting in a nice police station being read your rights.

You have the right to remain silent. It’s choosing to speak that will land you in trouble.