Catholic lay organisation, the Communita’ di Sant’Egidio, yesterday marked the 17th month since the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia expressing “gratitude for the truth she revealed”. Her memory was marked at the annual Sant’Egidio conference on ‘the soul of Mediterranean cities’ that is meeting this week in Livorno.

I had the privilege of speaking at the conference last night. My talk (in Italian) follows. Scroll down for an English translation.

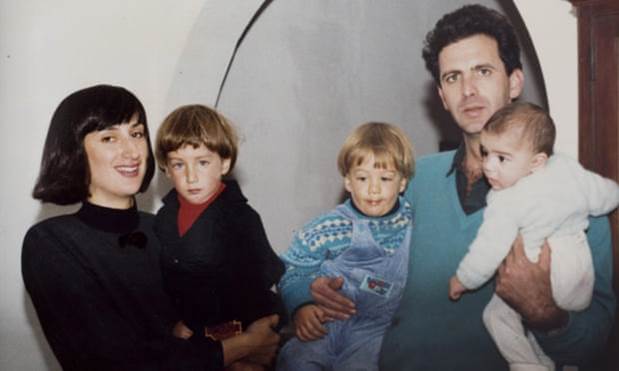

Photo: Maurizio Angioli

Il 16 ottobre 2017, alle 3 del pomeriggio, un’esplosione nelle vicinanze di un piccolo borgo al centro di Malta, uccise la giornalista più famosa dell’isola.

L’attributo “famosa” non può minimamente spiegare il ruolo che Daphne Caruana Galizia ricopriva nella società maltese al momento della sua morte.

Giganteggiava, nel contesto di un palcoscenico, troppo angusto rispetto alla sua bravura. Viveva in un borgo, nella periferia di una città, composto da un agglomerato di un centinaio di case. Molti degli abitanti di Bidnija sono contadini che curano la campagna maltese che si sta sempre restringendo, come dei giardinieri nel bel mezzo di una guerra.

Quando si sparse la notizia che una macchina era stata fatta saltare a Bidnija, nessuno pensò ad un’altra possibilità all’infuori dell’assassinio ineluttabile di Daphne. Questo non significa che tutti la considerassero una notizia orrenda. Dopo che il trauma iniziale si era attenuato un po’, molti hanno cominciato a festeggiare in privato, altri in pubblico. Molti ancora lo fanno.

La sua morte è stata un sollievo per tante persone, non necessariamente perché ne aveva parlato nei suoi scritti oppure perché avevano letto quello che aveva scritto e non gli piaceva. Per loro era come se fossero stati liberati dalla loro coscienza. Si sentivano svincolati da quella voce interiore che ti assilla quando sai che stai facendo una cosa sbagliata. Nel momento in cui lo specchio che Daphne aveva messo davanti alla società maltese era stato ridotto in mille schegge, loro sentivano di avere il diritto di ignorare le proprie pecche e di sguazzare nella loro avidità.

Come mai una cinquantatreenne, mamma di tre uomini sulla trentina, è stata fatta saltare in aria nella sua macchina, finendo smembrata, per il fatto che esercitava una professione che, fino a quel momento, era considerata non pericolosa, ovvero quella di scrivere sulla politica di un’isola mediterranea?

Questa è la domanda che continuiamo a chiederci ormai da 17 mesi, e benché molti avessero provato ad interpretare i segnali agganciati alla colonna di fumo della sua macchina arsa, non c’è ancora nessuna risposta definitiva. Conosciamo chi possa aver tratto giovamento dalla sua uccisione. Abbiamo anche dei sospetti su chi avrebbe avuto i mezzi per compiere questo delitto. Siamo molto frustrati perché questi nostri sospetti, condivisi da tanti, non sono stati oggetto di indagine da parte delle autorità.

Ma sappiamo anche che la spiegazione forense, anche se un giorno potrebbe portare alla scoperta dei mandanti di questo crimine, non potrà bastare per capire come tutto questo sarebbe potuto succedere.

All’università, Daphne Caruana Galizia ha studiato archeologia. La metodologia di quella scienza si è rispecchiata nelle sue interpretazioni delle scoperte giornalistiche. L’informazione viene fuori a strati e, più si scava in profondità, più fondamentale risulta l’informazione. Ma non ci si rende conto della profondità in cui l’informazione è nascosta, quando si cerca in superficie. I veri risultati si ottengono solo con tenacia, intuizione, pazienza meticolosa e lavoro instancabile.

L’unico indizio che ha in possesso un archeologo è il contesto. La possibilità di una scoperta, anche se senza nessuna garanzia, è misurata dalla conoscenza di quello che è stato scoperto prima; di quello che c’è intorno.

Raccontare la storia di Daphne Caruana Galizia e capire i motivi per cui è stata uccisa non possono perciò essere semplicemente il risultato di un’indagine della polizia scientifica. Questa potrebbe condurci agli esecutori che hanno avuto un ruolo da svolgere nell’ultima fase della sua vita, ma non può aiutarci a collocarla nel quadro complesso della realtà.

Lei è apparsa sulla scena giornalistica nei suoi vent’anni. Allora era già madre di tre figli. Si era sposata ad un’età giovane e si è messa nel campo del giornalismo dopo la nascita dei suoi figli. Quando ha cominciato a scrivere, il giornalismo maltese era dominio degli uomini coi capelli bianchi che scrivevano in modo anonimo e reverenziale.

Gli scritti di Daphne erano subito riconoscibili. Erano pungenti, taglienti e realmente indipendenti. Erano così particolari che praticamente da sola riuscì a mettere fine alla norma degli articoli non firmati. Il suo stile e la sua volontà indomita di sfidare il potere consolidato necessitava di essere rappresentato da una marca distintiva. Il suo nome – Daphne – è diventato la sua marca.

La sua opinione negativa del Partito Laburista maltese non è mai migliorata. Era una bambina negli anni 70 e 80, gli anni in cui un regime da cortina di ferro fece largo uso della violenza e della criminalità, ricorrendo anche all’omicidio orchestrato dallo stato, per perseguire le proprie finalità politiche oscurantiste.

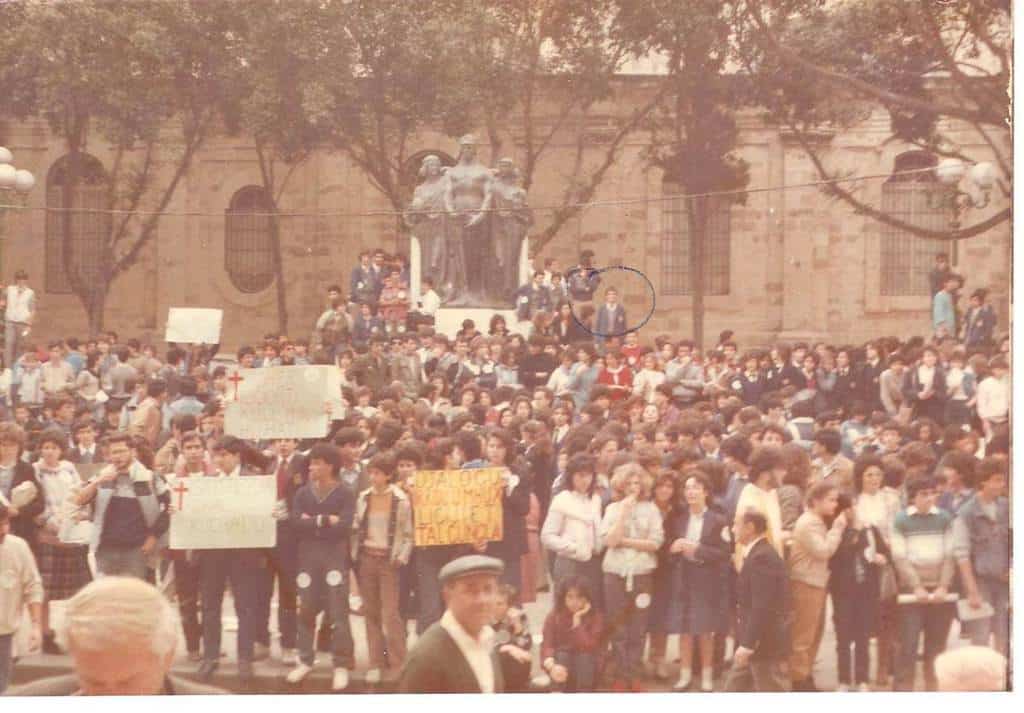

Da bambina lei ha vissuto in prima persona un’esperienza di questa politica oscurantista. Il regime socialista di quel tempo voleva abolire le scuole amministrate dalla chiesa cattolica, se non direttamente tramite un divieto totale, attraverso l’abolizione delle rette con l’intento di mandarle in bancarotta. La contesa finì con la chiusura di queste scuole per molti mesi e i ragazzi che frequentavano queste scuole venivano suddivisi in gruppi nei piani interrati per poter continuare le loro lezioni, nascondendosi come facevano i cattolici durante il periodo della riforma elisabettiana.

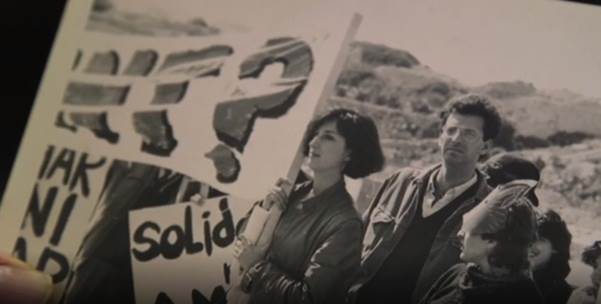

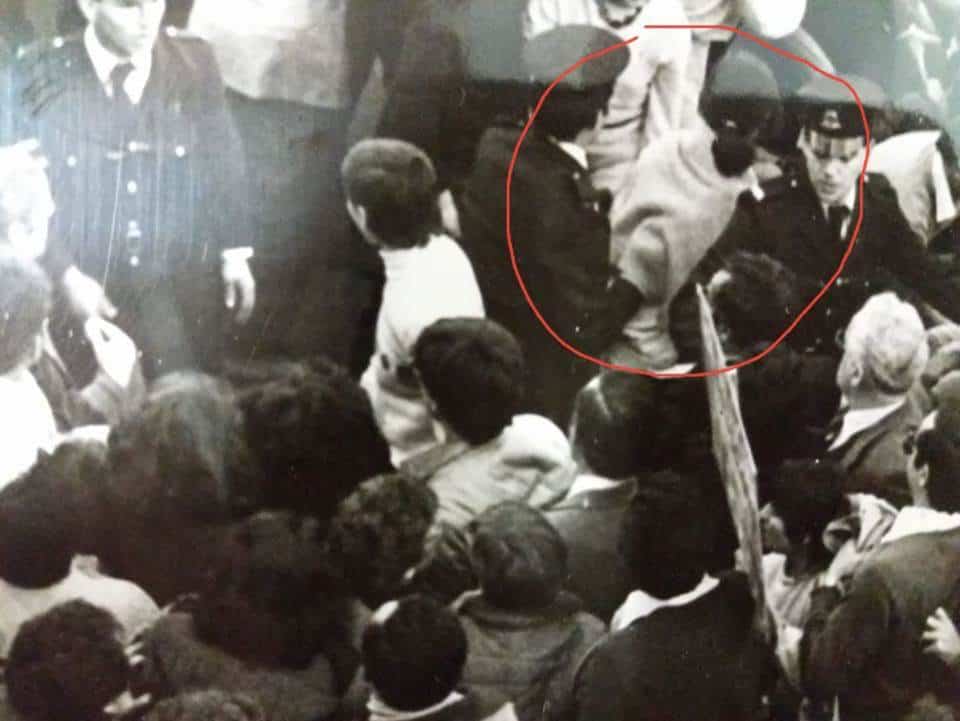

All’età di 19 anni lei partecipò a una semplice manifestazione di protesta. Una cosa del genere non era ben vista in quel periodo. Fu arrestata e chiusa in una cella sudicia. Fu interrogata e maltrattata da un ispettore baffuto della polizia che, in seguito, si diede alla politica, naturalmente con il partito laburista. Oggi è il presidente del parlamento maltese.

Ovviamente questo fatto ha valenza simbolica. Durante la maggior parte della sua carriera giornalistica, il partito laburista ha condotto una campagna per impedire che Malta diventasse parte dell’Unione Europea. Lei ha sempre creduto che l’isolamento e una pirateria basata su una scaltrezza di infimo ordine, quale l’economia off-shore, fossero ideologicamente ripugnanti.

E quando la generazione che ricorse alla violenza per sopprimere la democrazia negli anni 80 e la generazione che condusse la campagna contro l’adesione di Malta all’Unione Europea fino al 2003, fecero salire al potere l’attuale leader del partito laburista, diventato poi primo ministro, i suoi motivi di scagliarsi contro il detentore del potere tentacolare della politica maltese erano diventati ancora più pressanti e sempre più frustrati.

L’antagonista principale di questo dramma è l’attuale Primo Ministro di Malta, Joseph Muscat. Divenne capo del partito quando aveva 34 anni e poi Primo Ministro all’età di 39 anni.

Man mano che le elezioni politiche del 2013 si avvicinavano, l’esito diventava sempre più scontato. Ma Daphne, nei suoi articoli, sosteneva che era più che la semplice logica di alternanza di un sistema bipartitico che metteva in vantaggio il partito laburista di Muscat.

Da allora abbiamo saputo molte cose sull’ascesa meteoritica di questo nuovo leader, come anche sulle straordinarie risorse finanziarie di cui disponeva il partito laburista dopo che, nel 2008, era sembrato sul punto di andare in bancarotta. Queste risorse finanziarie stupefacenti nel 2013 cominciarono ad avere una spiegazione, solo pochi mesi dopo le elezioni politiche del marzo 2013, così pregne di conseguenze.

Sono accaduti tanti fatti durante quell’anno che hanno cominciato ad agevolare la comprensione.

Solo pochi mesi dopo le politiche del marzo 2013, Joseph Muscat guidò a Baku in Azerbaigian, una delegazione composta dal capo di gabinetto Keith Schembri e il suo ministro per l’energia Konrad Mizzi. Muscat conosceva il dittatore di Baku, Ilham Aliyev, da tanto tempo, a partire dagli anni della cosiddetta diplomazia del caviale, quando Joseph Muscat era un parlamentare europeo e Ilham Aliyev incantava politici di serie B con la sua generosa ospitalità.

Le visite a Baku erano senza nessun preavviso. Escludevano qualsiasi funzionario permanente, come anche la stampa. In seguito Konrad Mizzi si sarebbe intromesso direttamente, per costringere Malta a comprare combustibili dall’Azerbaigian, a prezzi più alti di quelli dettati dal mercato.

Ha firmato anche un contratto con un’impresa che opera in campo energetico, che poi avrebbe costruito la nuova centrale alimentata a gas. Un terzo di questa compagnia è proprietà della SOCAR, l’azienda di energia dello stato azero. Un altro terzo appartiene a un conglomerato di aziende maltesi.

L’amministratore delegato di questo conglomerato, Yorgen Fenech, possiede una società offshore a Dubai dal nome 17 Black. I Panama Papers avrebbero rivelato che 17 Black e un’altra società offshore a Dubai di cui ancora non conosciamo il proprietario, avrebbero pagato 5.000 dollari quotidianamente – 1,8 milioni all’anno – a due società panamensi chiamate Hearnville e Tillgate.

Queste due società offshore erano state create nella stessa settimana in cui Joseph Muscat diventò Primo Ministro. I PanamaPapers avrebbero poi rivelato che Tillgate e Hearnville appartengono a Keith Schembri e Konrad Mizzi.

Lo stesso giorno in cui Hearnville e Tillgate furono create, una terza società offshore dal nome Egrant fu creata contemporaneamente. Il proprietario – descritto come più importante dei proprietari delle altre due società – è rimasto un mistero.

Un altro fatto rilevante accadde pochi mesi dopo le elezioni del marzo 2013. Malta promulgò una nuova legge che permette al governo di vendere la cittadinanza maltese a miliardari, totalmente estranei al nostro paese – che non hanno mai vissuto a Malta e nemmeno lo faranno in futuro – ma che hanno i loro buoni motivi per spendere una somma a sei cifre per un passaporto di un paese dell’UE.

Per gestire il programma fu nominato un operatore svizzero, dai modi garbati – Christian Kaelin – che si presenta al mondo come un liberatore che scuote le cose e rompe le catene che reprimono le persone che vogliono essere liberi cittadini del mondo. Le persone povere e disperate a cui pensa sono gli oligarchi russi, gli sceicchi del petrolio saudita, i burocrati nigeriani ed i magnati cinesi.

Avremmo scoperto in seguito che Christian Kaelin lavorava in stretto contatto con Alexander Nix. Un anno fa, il signor Nix venne alla ribalta quando si dimise da una società, la Cambridge Analytica, la quale manipolava i big data per condizionare il comportamento dei votanti e usava delle strategie losche per incanalare gli esiti dei risultati elettorali.

Kaelin e Nix collaborarono in varie giurisdizioni nei Caraibi per assicurarsi che venissero eletti partiti politici impegnati ad introdurre lo schema della vendita dei passaporti, identico a quello maltese. In un caso specifico, si assicurarono che il partito all’opposizione che era contrario, collassasse.

Ancora un altro fatto, solo pochi mesi dopo le politiche del marzo 2013. Un iraniano trentatreenne, senza un giorno di esperienza bancaria al suo attivo, acquistò la licenza necessaria per aprire una banca europea a Malta. Si chiama Ali Sadr Hasheminejad. Un passaporto iraniano lo avrebbe intralciato nell’ottenimento dei documenti necessari. Perciò presentò uno dei suoi passaporti, quello di St Kitts and Nevis, emessogli da Henley and Partners. Dico “uno dei” perché sappiamo che ne aveva almeno un altro, ma con una data di nascita diversa.

Aprì la Pilatus Bank, un nome fantasioso per un ufficio di 10 persone e nessuna targa sulla porta.

Avremmo saputo più tardi che la Pilatus Bank serviva per il riciclaggio dei guadagni illeciti dei dittatori. Aveva solo 180 conti e la maggior parte di questi apparteneva ai capi supremi della dittatura di Baku, inclusi in modo molto prominente, due dei figli di Ilham Aliyev che usavano Malta per lavare il loro denaro sporco sulla strada che porta al loro stile di vita lussuoso in Gran Bretagna.

La banca aveva un altro cliente: Keith Schembri, capo di gabinetto del Primo Ministro, proprietario di una delle società offshore panamensi in fila per ricevere milioni dal consorzio operante ne campo dell’energia con cui aveva stipulato un contratto. I Panama Papers hanno rivelato anche che pagò l’amministratore delegato del giornale più letto a Malta – il Times of Malta – circa 650.000 euro di tangenti in un conto bancario nelle Isole Vergini Britanniche. Inoltre, saremmo venuti a conoscenza che nel suo conto presso la Pilatus Bank, Schembri riceveva tangenti dalla vendita dei passaporti.

Keith Schembri conosceva Ali Sadr Hasheminejad. Partecipò alla sua festa di matrimonio a Firenze nel 2015. Sapete chi era un altro invitato prominente? Joseph Muscat, il Primo Ministro.

Siamo venuti a sapere degli intrighi orditi dalla Pilatus Bank da Daphne Caruana Galizia che ha riportato informazioni fornitele da una fonte che lavorava in quella banca. Alla fine l’informazione fornita da quella fonte avrebbe condotto la Banca Centrale Europea a far cessare le attività della Pilatus Bank.

Ali Sadr Hasheminejad è fuori su cauzione nella zona dei tre stati a New York in attesa di essere processato nel tribunale degli Stati Uniti, un processo che comincerà il prossimo ottobre ed è accusato di frodi bancarie e violazione di sanzioni, accuse che potrebbero farlo finire in prigione per i prossimi 125 anni.

La fonte di Daphne Caruana Galizia scovò un altro pezzo d’informazione all’interno della Pilatus Bank. Quest’ informazione conteneva le prove che la terza società offshore panamense – la Egrant – apparteneva alla moglie di Joseph Muscat, Michelle, e vi venivano versati pagamenti a sei cifre dalla figlia di Illham Aliyev.

Va da sé, eppure mi sento in dovere di dirlo, che Joseph Muscat, Keith Schembri, Konrad Mizzi, Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, Christian Kaelin, e molti altri attori di questa rappresentazione teatrale, respingono tutte le accuse.

Tutta questa vicenda che vi ho raccontato, malgrado che sia sorretta dai fatti e dalle prove, è stata etichettata da Joseph Muscat come la più grande bugia della storia politica maltese. Si sostiene che sia tutta una finzione escogitata da una strega. E la strega è stata uccisa, bruciata come meritano le streghe.

Essendo a conoscenza di tutto questo e vedendolo coi propri occhi, come mai Joseph Muscat e la sua banda di truffatori continuano a sorridere stupidamente nelle foto di gruppo durante le riunioni del Consiglio Europeo?

Esiste un termine che veniva usato in passato per l’Ucraina e in seguito per la Russia: “L’appropriazione dello Stato”. Si verifica quando le istituzioni e gli apparati di uno Stato diventano una semplice copertura rispetto agli interessi privati di quelli che occupano posizioni di potere.

La Commissione di Venezia del Consiglio d’Europa ha recentemente esaminato il quadro costituzionale e istituzionale maltese e ha tratto la conclusione che il pensiero fondante – ereditato dalla tradizione britannica di comportamento irreprensibile – fa affidamento sull’autocontrollo di veri signori – gentlemen – e molto meno frequentemente, di vere signore.

Quando i truffatori s’impossessano di queste istituzioni, ogni parvenza dello stato di diritto crolla. Il Capo della Polizia è l’unica persona con l’autorità conferitagli dalla legge di indagare un reato. Quattro capi della polizia sono stati licenziati da Joseph Muscat fino a quando ne ha trovato uno totalmente disponibile a ignorare qualsiasi evidenza trovata contro i suoi boss politici.

Il Procuratore Generale è l’unica persona con l’autorità legale che può procedere in seguito a un reato. Ma nel nostro sistema antidiluviano, il Procuratore Generale fa anche da consulente al governo: agli stessi truffatori contro i quali dovrebbe procedere. In realtà si può avanzare una scusa formale per la vigliaccheria smidollata degli ufficiali che dovrebbero rispettare la legge.

Giudici e magistrati sono in teoria indipendenti ma sono nominati dallo stesso Primo Ministro che, in questi ultimi sei anni, ha stipato la magistratura di amici, inclusi l’ex vicecapo del partito laburista e molti altri ex candidati e ufficiali del partito.

In teoria abbiamo un’agenzia indipendente di intelligence finanziaria con il compito specifico di combattere il riciclaggio di denaro sporco. Infatti ha indagato Keith Schembri e Konrad Mizzi e ha determinato che c’erano motivi sufficienti per credere che hanno avuto a che fare con il riciclaggio di denaro sporco, come anche che hanno tratto profitto da ricavi illeciti.

Ma, a questo punto, queste conclusioni sono diventate di pertinenza dell’ufficiale di polizia in seno all’agenzia, responsabile di inoltrare queste informazioni alla polizia. Il suo nome è Silvio Valletta e sua moglie, guarda caso, è una ministra del governo di Joseph Muscat.

Silvio Valletta dirige il dipartimento di investigazione criminale della polizia, che gli ha assegnato dunque anche la responsabilità di condurre le indagini sull’assassinio di Daphne Caruana Galizia. La Corte Costituzionale ha già dichiarato, per ben due volte, che dato questo contesto, e in considerazione di chi possa essere sospettato del crimine, risulta incompatibile il suo ruolo di responsabile delle indagini sull’uccisione di Daphne. La sua posizione è altresì incompatibile per quanto riguarda le indagini sui reati commessi dai colleghi di gabinetto di sua moglie.

Valletta è a capo dello stesso dipartimento di polizia che ha perseguitato la fonte di Daphne Caruana Galizia della Pilatus Bank, che aveva informazioni segrete su Joseph Muscat. Maria Efimova dovette scappare da Malta, e passò un periodo in prigione, ad Atene, con una richiesta di estradizione da parte di Malta. Il tribunale greco ha rifiutato, per ben due volte, la richiesta di estradizione di Malta, temendo per la vita di Efimova.

Ma nessuno ha protetto la vita di Daphne Caruana Galizia. Lei era lo specchio che ha raccontato al paese questa lurida storia, un paese sequestrato da una banda di criminali.

Alle due e mezza del pomeriggio, di quel caldo pomeriggio del 16 ottobre 2017, lo specchio disse le sue ultime parole: “Ci sono ormai corrotti ovunque si volga lo sguardo. La situazione è disperata”.

La sua disperazione fu messa a tacere solo 30 minuti più tardi. La nostra era appena cominciata.

Photo: Maurizio Angioli

English Translation:

On the 16 October 2017, at 3pm, an explosion just outside a small hamlet in the centre of Malta killed its most famous journalist.

‘Famous’ does not begin to explain the status of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Maltese society at the time of her death.

She was a larger than life character on a theatre stage made for dwarves. She lived in a hamlet just outside town where no more than a hundred houses huddled together. Most of the inhabitants of Bidnija are farmers who take care of the shrinking Maltese countryside like gardeners in the midst of war.

When news spread that a car exploded in Bidnija no one thought of any other possibility except the final and inevitable demise of Daphne. That was not necessarily bad news for everyone. After the initial shock abated many were celebrating privately. Some were celebrating publicly. Many still are.

Her death was a relief to so many people not necessarily because she wrote about them or even because they read what she wrote and did not like it. For them it was like being stripped of conscience. They felt liberated from that inner voice that nags at you when you know you’re doing the wrong thing. Now that the mirror that Daphne held up to Maltese society was shattered in a thousand shards, they felt entitled to ignore their own warts and to wallow in their gluttony.

How did it come to pass that a 53 year old mother of 3 men in their 30s would end up blown to pieces in her car because she exercised the hitherto non-hazardous profession of reporting on politics on a Mediterranean island?

That is a question we have been asking ourselves for 17 months now, and though many have sought to interpret the signals from the smoke that bellowed out of her consumed car, there is no definite answer yet. We know who might have expected their lives to improve as a result of her killing. We have hints on who might have had the means to get the job done. We are frustrated that our shared suspicions are not tested by the authorities.

But we also know that the forensic explanation, even right up to the masterminds of this crime if ever they may be known, will not be enough to understand how this could have been possible.

At university, Daphne Caruana Galizia studied archaeology. The methodology of that science was reflected in her interpretations of the findings of her journalistic work. Knowledge is in layers and the deeper one digs, the more fundamental the knowledge that emerges. But the depth in which knowledge is hidden is unknown when you search it from the surface. Only tenacity, intuition, meticulous patience and indefatigable industry can yield results.

The only clue available to the archaeologist before they start digging is context. The likelihood of a find, though by no means the guarantee, is measured by someone’s understanding of what has been found before; what is around.

Telling the story of Daphne Caruana Galizia and understanding the causes of her killing cannot therefore be a mere forensic investigation. That may lead to the actors who played a role in the last act of her life but it would bring us no closer to understand where she fit in the grand scheme of things.

She first came on to the scene in her early 20s. She was already a mother of three little boys at the time. She married young and went into journalism after her sons were born. When she started writing, Maltese journalism was the purview of men with white hair who wrote anonymously and reverentially.

Daphne’s writing was immediately recognisable. It was caustic and sharp and truly independent. It was so distinctive that almost singlehandedly she forced the end of the convention of unsigned articles. Her style and her indomitable willingness to defy established power needed to be represented by a distinctive brand. Her name — Daphne — became that brand.

Her dim view of Malta’s Labour Party never brightened. She was a child of the 70s and 80s, the years when an iron curtain regime used liberally the tools of violence, street thuggery and state-perpetrated homicide to pursue its obscurantist policies.

As a child she experienced one of those obscurantist policies directly. The Socialist regime of the time wanted to abolish schools run by the Catholic Church, if not through an outright ban, by bankrupting them by abolishing school fees. The dispute led to a lock-down of many months as school children were huddled in basements to continue their classes in hiding like Catholics in the Elizabethan Reformation.

As a 19 year old she participated in a small protest march. That sort of thing wasn’t looked upon kindly at the time. She was arrested and locked up in a filthy cell. She was prodded and interrogated by a moustachioed police inspector. That inspector eventually went into politics, naturally with the Labour Party. He is today the President of Malta’s Parliament.

Of course the incident is purely symbolic. For most of her career as a journalist the Labour Party campaigned to prevent Malta from joining the European Union. She found isolation and a piracy of cheap cunning of an off shore economy ideologically abhorrent.

And when the generation that used violence to suppress democracy in the 1980s and the generation that campaigned against EU membership up to 2003, passed the helm to the leadership that runs the Labour Party and Malta today, her reasons for pitting herself against that behemoth of Maltese politics became even more urgent and increasingly more frustrated.

The principal antagonist of this drama is Malta’s present Prime Minister, Joseph Muscat. He took over the leadership of the party when he was 34 and would become Prime Minister at 39.

As the 2013 election got closer the likelihood of his election was becoming practically a certainty. But Daphne, writing at the time, was arguing that more than the mere logic of alternation in a two-party system was favouring Muscat’s Labour.

Since then we have learnt much but the meteoric rise of this new leader and the extraordinary wealth the Labour Party appeared to have come into between its near bankruptcy in 2008 and its stupefying resources in 2013 was already becoming understandable within months of that fateful election in March 2013.

Many things happened in that year that we could see.

Within months of the March 2013 election Joseph Muscat would lead a delegation made of his Chief of Staff Keith Schembri and his Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi to Baku in Azerbaijan. Muscat had known the dictator of Baku, Ilham Aliyev, for many years, harking back to the caviar diplomacy years when Joseph Muscat was an MEP and Ilham Aliyev charmed B-grade politicians with his generous hospitality.

The visits to Baku were unannounced. They excluded any permanent officials and the press was kept away. Eventually Konrad Mizzi would interfere directly to force on Malta the purchase of fuels from Azerbaijan at prices higher than market rates.

He would also close a deal with an energy company to build a new gas-powered power station. A third of the company is owned by SOCAR, the Azeri state energy firm. Another third is owned by a conglomerate of Maltese businesses.

The CEO of that conglomerate, Yorgen Fenech, owns a Dubai company called 17 Black. The PanamaPapers would reveal that 17 Black and another Dubai company whose owner is not known would be paying $5,000 a day — $1.8 million a year — to two Panama companies called Hearnville and Tillgate.

These two companies were set up that week in March 2013 when Joseph Muscat was made Prime Minister. The PanamaPapers would reveal that Hearnville and Tillgate belong to Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi.

On the same day that Hearnville and Tillgate were set up, a third company called Egrant was set up with them. Its owner — described as more important than the owner of the other two companies — remained a mystery.

Something else happened within months of that March 2013 election. Malta adopted a new law that allowed the government to retail Maltese citizenship to billionaires, entirely unconnected with the country — who never even lived in Malta and never would — but who had reasons to spend six figures on the passport of an EU country.

To run that scheme the country appointed a suave Swiss operator — Christian Kaelin — who introduces himself to the world as a liberator who breaks the shackles and the chains that inhibit people from becoming free citizens of the world. The poor and desperate people he has in mind are Russian oligarchs, Saudi oil sheiks, Nigerian bureaucrats and Chinese tycoons.

We would eventually learn that Christian Kaelin worked in close association with Alexander Nix. A year ago Mr Nix came to prominence when he resigned from a company called Cambridge Analytica that manipulated big data to condition voting behaviour and used dirty tricks to control the outcomes of election results.

Kaelin and Nix worked together in several Caribbean jurisdictions to secure the election of political parties committed to introduce passport schemes identical to Malta’s. In one case they worked to secure the implosion of an opposition party that was against it.

Something else happened within months of that March 2013 election. An Iranian 33 year old man without a day of experience in a bank was given a license to open a European bank in Malta. His name is Ali Sadr Hasheminejad. An Iranian passport would have prevented him from acquiring paper clips in Malta. So he presented one of his St Kitts and Nevis passports issued to him by Henley and Partners. I say ‘one of’ because we know he had at least another one but that had a different date of birth.

He opened Pilatus Bank, a fancy name@ for an office for 10 people and no sign on the door.

We would eventually learn that Pilatus Bank was a laundry for the ill-gotten gains of dictators. It had but a 180 accounts. Many of them belonged to supremos in the Baku dictatorship, including, most prominently two of the children of Ilham Aliyev who used Malta to clean their dirty money on its way to their expensive lifestyles in the UK.

He had another client: Keith Schembri, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, owner of one of the Panama companies lined up to receive millions from the energy consortium he contracted. The PanamaPapers also revealed he paid the Managing Director of Malta’s newspaper of record — Times of Malta — some 650,000 euro in bribes in a British Virgin Islands account. And, we would learn, in his account at Pilatus he received kickbacks on the sale of Malta’s passports.

Keith Schembri knew Ali Sadr Hasheminejad. He went to his wedding in Florence in 2015. Another prominent wedding guest? Joseph Muscat, the Prime Minister.

We would learn about the goings on at Pilatus Bank from Daphne Caruana Galizia who reported information provided to her from a source who worked at the bank. Eventually the information provided by that source would lead to the European Central Bank shutting down Pilatus Bank.

Ali Sadr Hasheminejad is bailed out in the New York tri-state area awaiting a trial in the United States court starting this October on charges of bank fraud and sanctions-busting that could see him spend the next 125 years in prison.

Daphne Caruana Galizia’s source brought another piece of information from inside Pilatus Bank. It held evidence that that third Panama company — Egrant — was the property of Joseph Muscat’s wife, Michelle, and it was used to receive six-figure payments from the daughter of Ilham Aliyev.

Needless to say, but I am obliged to, Joseph Muscat, Keith Schembri, Konrad Mizzi, Ali Sadr Hasheminejad, Christian Kaelin, and many other actors in this drama deny any wrongdoing.

All of the story that I told you, in spite of the evidence that backs it up, is branded by Joseph Muscat as the biggest lie in Malta’s political history. It is then a fiction conjured by a witch. And the witch is dead, burned as witches must be.

Knowing all this and seeing all this, how is it that Joseph Muscat and his gang of crooks continue to smile inanely at family photos of European Council meetings?

There’s a term which was used in the past for Ukraine and eventually for Russia: ‘State capture’. It’s a state of being when the institutions and trappings of a State become merely a cover for the pursuit of the private interests of those who occupy positions of power.

The Council of Europe’s Venice Commission has recently assessed Malta’s constitutional and institutional framework and found that the design — inherited from the ever so polite British — relies on the self-restraint of gentlemen and, far less frequently, gentlewomen.

When crooks take over those institutions, any semblance of the rule of law collapses. The Chief of Police is the only person with the legal authority to investigate a crime. Four Police Commissioners were fired by Joseph Muscat until one entirely willing to ignore evidence against his political bosses was found.

The Attorney General is the only person with the legal authority to prosecute a crime. But in our antediluvian design the Attorney General is also counsel to government: to the same crooks who ought to be prosecuted. There is actually a formal excuse for the spineless cowardice of the officers who should enforce the law.

Judges and Magistrates are in theory independent but they are appointed by the Prime Minister himself who has used the last 6 years to stuff the bench with cronies including a former Deputy Leader of the Labour Party and several other former candidates and officials.

In theory we have an independent anti-money laundering intelligence agency. It has indeed investigated Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi and found sufficient reasons to believe they have committed money laundering or benefited from proceeds from crime.

But when that is done it goes up to the police officer responsible to move the file from the intelligence agency to the police proper. His name is Silvio Valletta and his wife, of all things, is a Minister in Joseph Muscat’s government.

He heads the police’s criminal investigation department which also gives him the responsibility to lead the investigations into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia. The Constitutional Court found — twice — that his proximity to likely suspects of the crime makes his headship of the Daphne investigation out of order. There’s no reason to think his position is in any better order when he’s heading investigations into crimes committed by the Cabinet colleagues of his wife.

He heads the same police department that hounded Daphne Caruana Galizia’s source at Pilatus Bank who had the goods on Joseph Muscat. Maria Efimova ran away from Malta, and spent some time in an Athens prison on the back of an extradition request from Malta. The Greek courts — twice — refused Malta’s request for her extradition fearing for her life.

But no one protected Daphne Caruana Galizia’s life. She was the mirror that told the country this grimy story of its capture by crooks.

At 2.30 pm, that hot afternoon of the 16th October 2017, the mirror spoke its last words: “There are crooks everywhere you look now. The situation is desperate”.

Her despair was silenced but 30 minutes later. Ours had just begun.