Updated 27 August 2020 at 09:30 (see bottom of post).

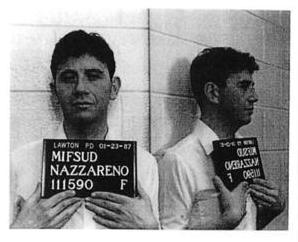

The United States’ request for extradition of fugitive Reno Mifsud deserves close watching because it is a test of the Malta-US extradition process.

According to documents filed in the US District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, when Reno Mifsud fled from the United States prior to his 1987 trial, the US authorities believed he found refuge in Malta.

“However, his extradition from Malta was not sought at the time because it was believed that extradition would not have been granted.”

At the time, Malta and the US worked with the extradition treaty agreed between the United States and Great Britain in 1931. The treaty was made applicable to Malta on 24 June 1935.

That treaty ruled out the possibility of either country extraditing any of its citizens to the other. Reno Mifsud, was both a US and Maltese citizen and therefore the US did not expect Malta to extradite him back.

In 2006, the United States and Malta signed a new extradition treaty that entered into force on 1 July 2009. The new treaty provides that “extradition shall not be refused based solely on the nationality of the person sought” in the case of certain crimes including “sexual exploitation of children and child pornography”.

In 2015, US Marshals received intelligence about Reno Mifsud living in Malta. They worked with the US Embassy in Malta, the Pentagon and the US Army Criminal Investigation Command to locate Reno Mifsud and draw up the documentation to ask for his extradition.

A Maltese court is now being asked to order the extradition of a Maltese citizen to face justice in the United States. This is not a common occurrence and one that may anticipate the use of the extradition process for other unconnected cases.

Financial crime blogger Kenneth Rijock, in a post last night, referred to the possibility of indictments of Maltese citizens involved in breaches of US financial laws committed at the shuttered Pilatus Bank.

“Potential defendants include senior government officials, regulators, Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs), and the usual Maltese financial crime suspects,” says Kenneth Rijock.

Reno Mifsud’s case will give some form of an indication of the willingness of the Maltese authorities – government, police and courts – to co-operate with American law enforcement agents seeking to bring Maltese citizens to justice. Having said that, the extradition of a man charged with molesting minors in his care would quite likely prove less problematic than the extradition of senior officials in the administration or politically exposed persons.

Update 27 August 2020 at 09:30

Though court papers from Oklahoma suggest the US authorities believed extradition from Malta could not happen under treaty provisions in force before 2009, this is not borne out by the facts.

This is a link to the treaty in place before 2009 that governed extraditions from Malta. It is the 1931 agreement between the UK and the USA and makes no specific exception for the extradition of citizens of the country in which the persons on whom extradition is requested are found.

And this is a link to a 2007 decision in the Maltese courts that ordered the extradition of a Maltese citizen to the US. This happened before the new treaty came into force.

Whether as a result of law, or as a result of applicable policies in different times, or as a result of mistaken impressions, it remains a fact that the US authorities made the request for Reno Mifsud’s extradition after the coming into force of the new treaty, believing, for whatever reason, that chances of Malta’s cooperation with extradition have now improved.