I think that the brief exchange between Victoria Buttigieg, at the time deputy attorney general, and lawyers for Electrogas published yesterday by Matthew Caruana Galizia deserves further reflection.

The exchange comes out of the leak of Electrogas emails that was sent to Daphne Caruana Galizia a little before she was killed. She was killed, it looks increasingly clearly, to prevent her from reading those emails and publishing what they say. The murder was executed to prevent the discovery of corruption. But there is more those emails might uncover.

One other thing this short exchange of emails uncovers is yet another illustration of the collapse of our institutions.

Victoria Buttigieg’s role at the time of conducting this exchange with the Electrogas lawyer was as counsel to government. The government relies on her to advise it, to act exclusively in its interests. “The government” is not the persons who happen to sit in office at the time. Those people – Konrad Mizzi, Keith Schembri, Joseph Muscat – are elected to run the government. Since this is not an absolute monarchy their personal desires and interests are not the same as the interests of the country’s government.

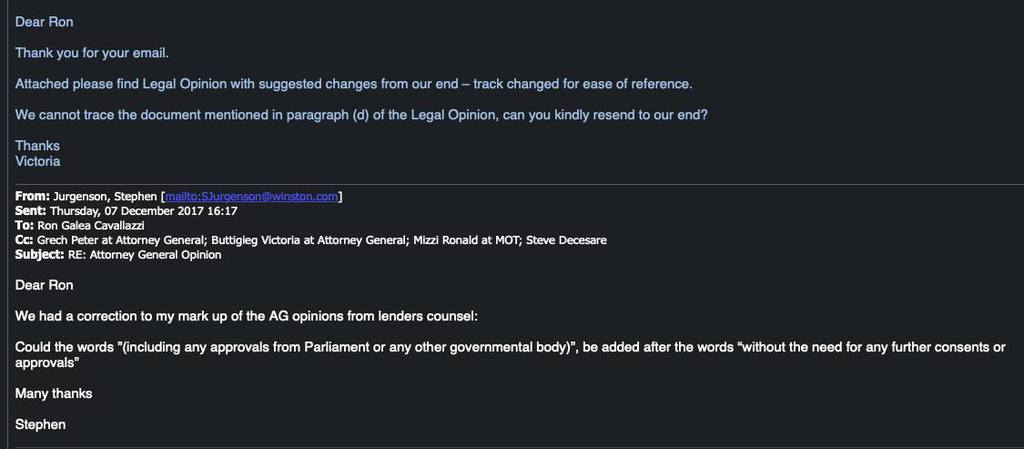

The emails show that Victoria Buttigieg was working on a draft written opinion for her client: the government. The opinion was needed to address the question whether the minister of state (Konrad Mizzi) needed to get explicit authorisation from the college of ministers (cabinet) before entering into the Electrogas deal. More importantly perhaps her opinion was needed to verify whether it was necessary for the executive (the government) to get the permission of the legislature (parliament) in order to enter the deal.

I have not seen the opinion and in any case my purpose here is not to comment on the substance of the advice and whether it was written on the basis of the law or what Konrad Mizzi (and Joseph Muscat and Keith Schembri and Yorgen Fenech) wanted the law to be. I did that yesterday.

My purpose here is to comment about the fact that this email exchange shows that the advice the government was seeking from its own lawyer was being drafted by the lawyers of the external actors with whom the government was negotiating. Now this is problematic, very problematic.

There’s a gashing ethical question here. A legal opinion written by a lawyer for its client is a confidential affair. Only the client can decide whether to release it. This is especially and most obviously the case when the outcome of the opinion has a material impact on the position the government ought to take with respects to actors outside it, in this case the owners of Electrogas.

When the lawyer is the Attorney General and the client is the government, the opinion is not just a professional secret; it’s an official secret, a secret of state.

But what’s really jaw dropping here is that what was bouncing between the email accounts of the staff at the Attorney General’s office and lawyers working for Electrogas wasn’t a legal opinion yet: this was a draft legal opinion. This was in a state of deliberation and preparation where alternative legal paths are assessed before one is ultimately chosen for the final advice. If the final result is a state secret, the deliberative stage is a sacred secret. If, as has happened in this case, people from outside government who stand to profit or lose out of the direction the advice ultimately takes are allowed in the deliberations, considerations outside the law come into play.

This is not the negotiation of the contract. This is not a negotiation at all. This is a review of the correct approval procedure within the structures of the state, regarding which the views of a private contractor are completely and utterly irrelevant. Deference to the desires of Yorgen Fenech and the other owners of Electrogas – in this case the desire that after Konrad Mizzi no one else takes another look at the deal – is betrayal of the client’s trust. It is the usurpation of the public interest by entirely private interests.

I don’t want to wallow in fake outrage. We have long figured out that this sort of thing had become the order of the day in the conduct of government business. There is no way that any diligent safeguard of the public interest would have allowed Joseph Muscat’s gang of crooks to run riot with public funds and to commit the country to deals that made no sense to anyone except those profiting from them, certainly not the public at large.

But in this short exchange of emails we are seeing the hard evidence of this sort of conduct. I have no doubt Victoria Buttigieg at the time felt she was doing her job to the best of her ability. It was all part of the “business friendly”, “go getting” methodology of the government of the day where corruption and collusion were dressed as political entrepreneurship and result-oriented government. Look where that got us.

Consider this. Since the role of the Attorney General has been entirely focused on criminal prosecutions and the designation has become a historical legacy for what should more properly be called Chief Prosecutor, you would expect that a person appointed to that position would be some sort of expert on criminal law. They would have climbed the ranks conducting successful prosecutions, putting behind bars the most hardened criminals and showing the bad guys what’s what.

Instead they hired for the post Victoria Buttigieg for whom the criminal court is a spectator sport, not a professional playing field. So, if her lack of expertise in criminal law and the absence of any record in successful prosecutions did not block her way to this appointment, what credentials did she need to get the job?