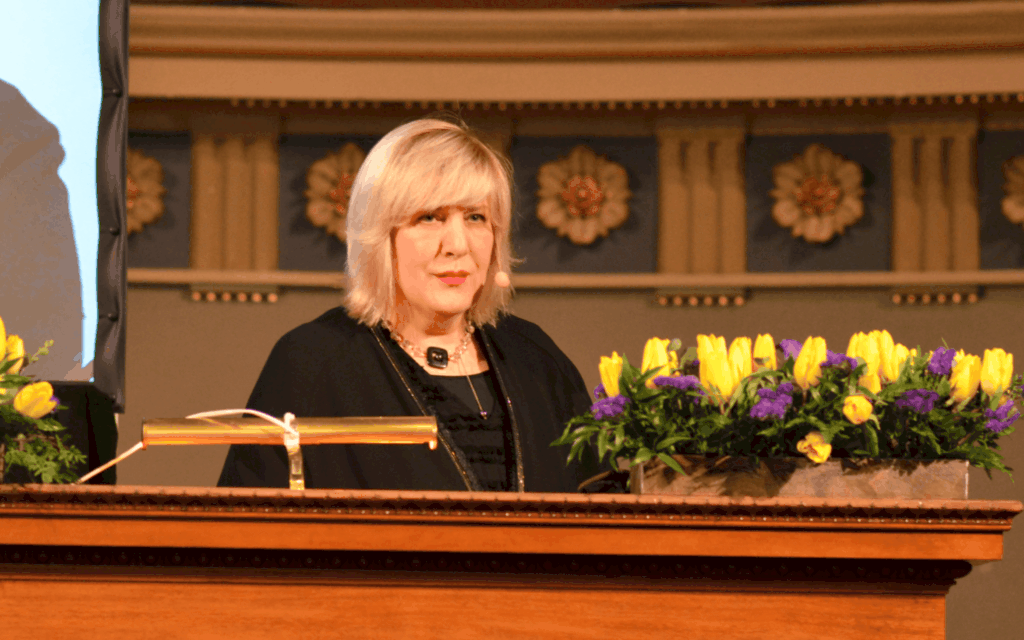

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights is visiting Malta this week for meetings with the local authorities and civil society. Dunja Mijatovic will have quite an agenda. Malta is not the most complicated country for human rights in the Council of Europe. Her conversations in Russia, Turkey, and Belarus are bound to be darker. But setting ourselves against the background of the worst is a very low standard to aspire to. We’ve been better and we could be better. It is not just the low standards that we have fallen to that are of concern, it is the trend of continued erosion.

Officially, the prison is now a drug-free area. That, no doubt, is an indicator of something. But human rights are measured by other indicators. Consider the rate of suicides in prison. Consider consistent reports by inmates and wardens of systemic abuse, fear, overcrowding, discrimination, racism, transphobia, and psychological and physical violence. Consider the weakness of oversight, the official indifference of the civil authorities, the draconian restrictions on access for the press, and the secrecy surrounding external investigations. The prison is not only a drug-free area. It has now also become a human rights-free area. It has become a gulag run by an armed gauleiter gone mad.

There have been improvements to the physical conditions in detention centres for undocumented migrants, at least in areas that have finally been open to visits by the press. But even if the Midnight Express set has been given a good lick of paint, the draconian penalty of long-term and indefinite imprisonment for people whose crime is escaping the misery of their country remains in force. The government does not hesitate to describe its policy of indefinite detention as a “deterrent”, punishing the survivors to warn others that could consider following them that the hell they live in is cooler than the hell that awaits them here.

Less explicit is the deterrence of the lottery of rescue. When politically expedient to do so, the Maltese authorities have shown themselves perfectly capable of ignoring their legal and moral obligation to rescue people drowning in our waters.

Although Malta’s human rights record is incomparable with Libya’s and conditions in migrant detention centres in Malta are positively luxurious in comparison with conditions in Libyan camps, Malta’s standards are as low as the countries it works with to prevent migrants from making land. Pushing migrants to Libya is not merely illegal, which it is. It is also making our own the treatment levelled at migrants by Libyan authorities or Libyan militiamen. On our conscience then, the inhuman treatment, slavery, unexplained disappearances, rape, and physical abuse perpetrated in the Libyan camps that we dispatch people we push out of our waters.

On shore our methods of “deterrence” are also atrocious. We have criminalised the act of rescuing someone at sea, arresting boats and prosecuting rescuers intentionally confusing the act of fishing out souls nearly lost to water with smuggling and slave trafficking.

That’s the same obtuseness as the wilful confusion of the rare ability of three migrants to translate for other rescued passengers lost, half-blinded and agonised after deserts of sand and salt, with terrorism and piracy, slamming boys who dreamt of freedom with the risk of life in prison.

The first measure of respect for human rights is how a government and community treats people from outside it. Humanity considers itself as such because it is able and willing to treat strangers well, to tend to the wounded, rescue the drowning, and shelter the lost.

Our worst human rights offences are served to people of other races, particularly black people whom we deprive of their innate status of humanity, depriving ourselves of it in the process as well.

Even so, though more subtly and less grievously, our authorities’ respect for human rights within our community is short of what we’re entitled to expect in a mature democracy.

Consider the conduct of the authorities when they are faced with criticism that displeases them. When civil society asked for the authorities to assess the behaviour of ministers when they abandoned migrants lost at sea to their fate or pushed them back to Libya, the reaction was horrific. The prime minister and his ministers used their unequalled access to the media to fall down on their critics accusing them of treason and hauling them for lynching. The police waited for the turn of a government-friendly magistrate to process the complaint and the magistrate made a dog’s breakfast of the investigation denying justice to 12 people allowed to drown and almost 60 pushed back to living hell in Libya.

The incident is symptomatic of the government’s understanding of the role of civil society in a democracy. It is a very poor understanding. Consider the much vaunted, never delivered reforms to the Constitution to protect and enhance our democratic design. It has been coming up in public discourse for 8 years now but no substantive discussion has started. It seems likely that we’ll get a metro system before we get a proper discussion on democratic reforms.

Presidents came and went, all promising proper engagement with civil society. None happened. In the meantime, as and when it suited them, government introduced piecemeal legislation making changes to the Constitution or to other important laws without any public consultation or debate to speak of. When the Venice Commission pushed the government to make changes they were shocked to find the government did not consult civil society. They had to conduct the consultations themselves to make sure they’re hearing all the bells.

The government will ignore civil society’s calls for meetings and public consultation unless there is the opportunity for comfortable PR reducing civil society from the status of player and partner in a democracy to a stage prop.

In the meantime, the government will legislate to make it near impossible for voluntary organisations to secure funding and will open frivolous investigations to persecute NGOs it does not approve of or discredit them altogether.

Malta is not Turkey or Belarus. Inconvenient civil society activists do not face the risk of prison or disappearance. But they will be ignored. And that’s just not good enough. Don’t think of Repubblika and the noise it makes because – you might be inclined to prefer to believe – they are a bunch of Nazzjonalisti maħruqin. Think of the contempt for activists demanding reforms in prison, or in the treatment of migrants, or for the adherence to planning rules in the laws the politicians write and discard.

And the Maltese authorities do use tools that would be far likelier in Turkey and Russia than in a normal European democracy. One TV is straight out of George Orwell’s nightmares. It has a license to lie wilfully, to discredit people it misrepresents as belonging to the artificial dichotomy that suits the government so well. If all opposition or dissent is reduced to a single minority view labelled “nazzjonalisti”, if public discourse is reduced to only two possible alternatives, the winning or the losing, then they win every argument without having to listen to any other point of view.

Political parties are entitled to promote their positions and criticise their opponents. If they must do so on a TV station they own, so be it. This does not mean they can slander, dehumanise, isolate and demonise anyone whom they perceive as an obstacle to their monopoly on power. And they should restrain themselves to picking on someone their own size (other political parties) not extending this to journalists, activists, or people whose contribution to political debate does not come with state power.

What makes all this worse is the government’s abuse of public broadcasting as a vehicle for propaganda. Public broadcasting is supposed to be the media agora of free and open debate. It should be a source of dispassionate information and education, a platform to give voice to minorities without access to their own media resources, an impartial space for journalists and producers to pursue the evidence wherever it takes them, even if the destination is inconvenient for the government of the day.

Again, our TVM journalists do not risk prison like their colleagues in Turkey or Belarus. But they’re a lot like journalists working in European countries before these could describe themselves as democracies and join the Council of Europe. Journalists working for TVM are Soviet loyalists, propagandists, or, in some cases, auto-lobotomised salary-collectors.

Is this important? Is this a discussion about human rights? Yes. We can’t just be grateful to the authorities for respecting our right not to be imprisoned without process (even as they breach that right for others who walk among us while being black).

We have a right to associate in organisations to have our views heard, even as minorities, indeed especially as minorities. And we have a right to be informed by a media landscape that is designed to expose, document, and comment on the truth so that we can be citizens of a free democracy not drones that tick off ballots to extended Labour’s grip on power indefinitely.

Propaganda on One TV, selective adulation on TVM, and hate-campaigning over social media, organised by the Labour Party, for which in the present context, read the state. Eye of newt, and toe of frog, and you get a recipe for the degeneration of human rights and democracy that makes us look comfortable against the background of other members of the Council of Europe that are democracies only in name.

It should not be surprising then that Malta still does not have an umbrella body to monitor, promote, and educate the public on human rights. That’s because the government is selective about which human rights to promote. Promoting equality in gender is politically convenient so we get a commission to promote equality (gender, gay rights, and so on). Good.

Promoting the respect of the rights of migrants or pushing back on the restrictions on critics of the government is not politically convenient so if you want someone to discuss that with, you’ll need to wait for the prime minister to give you an appointment which he won’t. Bad.

Fortunately, the European Commissioner for Human Rights has such an appointment this week. For a country that used to be a functioning democracy, she has quite an agenda ahead of her.