The nineteenth century movements in Europe that would eventually call themselves nationalist were disparate and distinctive. Indeed there were as many “nationalisms” as there were nations. The method of elite nationalist movements was replicable, by and large: design a culture, reverse engineer its pedigree and proclaim its rights to self-determination. But the details were never the same.

The oddest things happened when these cultures were being designed. Remember that scene in Braveheart when Mel Gibson’s William Wallace and his army lifted their kilts and mooned the English? Well one historical inaccuracy there was the kilt (and by inference the mooning was more literary license). William Wallace and all the lowlanders wore trousers at the time. But the identity of the Scottish nation, particularly its distinctiveness, was projected back from the pens of the Scottish nationalists on a history they re-wrote centuries later to serve their political ends in their own time.

The oddest things happened when these cultures were being designed. Remember that scene in Braveheart when Mel Gibson’s William Wallace and his army lifted their kilts and mooned the English? Well one historical inaccuracy there was the kilt (and by inference the mooning was more literary license). William Wallace and all the lowlanders wore trousers at the time. But the identity of the Scottish nation, particularly its distinctiveness, was projected back from the pens of the Scottish nationalists on a history they re-wrote centuries later to serve their political ends in their own time.

There are plenty of these ‘invented traditions’, as Eric Hobsbawm called them. They are often manifested in national costume (as with tartans in Scotland), food, music and other aspects of culture that are artificially projected on the past to serve the politics on what was the present for 19th century nationalists.

There are plenty of these ‘invented traditions’, as Eric Hobsbawm called them. They are often manifested in national costume (as with tartans in Scotland), food, music and other aspects of culture that are artificially projected on the past to serve the politics on what was the present for 19th century nationalists.

Language was frequently an invented tradition. European Jews had not spoken any Hebrew outside synagogue for centuries. Most European Jews spoke Yiddish, a perfectly distinctive language that inconveniently was a dialect of German. So Zionists effectively codified a new language, modern Hebrew, loosely related to the classic Biblical language, and made it the language of the new Israeli state.

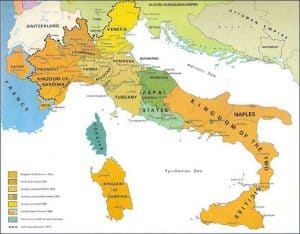

The Italians did the same, choosing a specific dialect from a fraction of the Italian peninsula, until the mid-19th century merely a “geographical expression”, and made it the standard unifying language of the nation they wanted to build even though it was barely familiar to most of its people.

The Italians did the same, choosing a specific dialect from a fraction of the Italian peninsula, until the mid-19th century merely a “geographical expression”, and made it the standard unifying language of the nation they wanted to build even though it was barely familiar to most of its people.

The Maltese imitated this. At first by cultivating the Italian language here, arguing Malta was l’estremo lembo del nido italico and eventually resorting to Maltese, a language barely ever written, now codified in the Latin alphabet and endowed with literary historical apocrypha creating myths and legends of Malta’s own Arthurian dark ages.

The Greeks re-invented a language to energise their struggle to quit the Ottoman Empire. They dug up ancient Greek, spoken millennia before by a people ethnically unrelated to them, and re-invented an old language for modern use. But a great distinctiveness the Greeks had from the Ottomans was that they were a Christian minority in a Muslim empire. Christianity was recruited as a unifying identity for the disparate people of the Peloponnese and as a sharp distinction from the Muslims.

Other nationalist movements adopted religion as an invented tradition, an aspect of the founding mythology of the nation seeking redemption and liberation. But never in the same way.

Consider how Irish Catholicism was central to the movement to separate from Protestant Britain and how the denominational barrier remained the front line of conflict between Republicans and Unionists in the unredeemed north. Contrast it with how Italian nationalism was anti-clerical and anti-Catholic since the Catholic Church, a temporal and territorial power in the centre of the geographical expression, was a barrier to the realisation of the nation, rather than a catalyst.

In Malta Catholicism has a duplicitous effect on the forming of the national cult. Certainly the distinctiveness of Catholics from the Protestant colonisers was emphasised by the nationalists. They proclaimed a direct line between their faith and Saint Paul – in Valletta, in February, you can still hear inebriated enthusiasts insisting that “San Pawl Nazzjonalist!”.

They also invented the de-islamification of Malta with the arrival of the Normans in the 11th century.

Nationalist elites used Catholicism as evidence of a European pedigree in contrast with the other peoples the British colonised which were perceived as inferior for not being civilised enough for Christianity. Christianity gave Maltese a right to self-determination in contrast with the polytheism and animism of Africans that still depended on the white man’s burden of civilising the inferior people of the world.

In the same way that Christianity proved Maltese whiteness, its newly codified language, at first glance a distinct heir to Latin and therefore a cousin of Italian and French not squiggly black gibberish to our south, was more proof of our eligibility to self-determination or at least dignified unification with our Italian home. That was why they codified the Maltese language in a Latin alphabet, wholly inadequate for our semitic language but more European and Christian if only in appearance.

Though Catholicism was central to the Maltese nationalist mythology, the Catholic Church itself, as an institution was as inconvenient to nationalist politics in Malta as it had been in Italy. Although not quite a papal state, Malta’s colonists recruited the Catholic Church as the established religion of the state, replacing in all but the vestments the role of the Church of England. The colonists secured the collaboration of the ecclesiastical nomenklatura to push back against Maltese nationalism.

The Partit Nazzjonalista was a central part of this drama that unfolded right up to the rise of fascism in Italy in the 1920s and 30s. It outlived that phase and moved on from ethnic and national identity politics as these became redundant with the fall of fascism, the cold war and the changing role of nation states, decolonisation and European integration. All over Europe the quirky invented traditions that held so much political significance for a hundred years after the end of the Napoleonic wars had now become colourful features on tourism brochures. Or unspoken embarrassments that are better not repeated like all that rubbish about our unjustified sense of superiority on spurious racial grounds.

The PN’s gold-rimmed flag and its pompous oompah anthem are not the only residues left to us from that time. Band clubs in villages with rivalries between La Stella and King’s Own whose origins are all but forgotten but whose paraphernalia are as pervasive in our landscape as sandstone are another aspect of this. So are the hysterical cheers and jibes at English and Italian football teams that we renew every few years in spite of our own shame.

But no one deems these as casus bellis. There may be individuals who among other considerations define their identity by their Catholicism. There may even be individuals who among other considerations define their identity by their familiarity, sympathy and enthusiasm for Italian culture. There may even be individuals who define their identity by both of those things.

But I haven’t met many people who define being Maltese limitedly to being Catholic and having an Italianate attitude. Even if there were any who did, fewer of them yet seriously believe politics and policies should be designed to serve the interests of Catholics and Italianates at the exclusion of others.

Over time, without the artificial pressures of elites mobilising people against a colonising other, our understanding of what makes us who we are has evolved and there is certainly no unanimous view of the entry requirements for Malteseness. Why should there be?

Objective criteria are needed for citizenship, if anything. Citizenship is a legal status while identity is a psycho-social one. You can have hard and fast rules for legal eligibility but hard and fast rules on what people should “feel” Maltese is an absurd notion.

Beyond an affection for pasta and frequent driving holidays, italianità has long faded from most people’s minds: certainly anyone under 40. Catholicism remains the largest denomination but is hardly alone anymore. Churchgoers are now a large minority and the people who believe national policy should be written in the curia are few and far between and I hazard a guess none of them actually work in the curia.

There is an ugly trend to adopt anachronistic foundation myths to mobilise hate against racial and immigrant minorities who like the colonists of other centuries are slandered as invaders and contaminators of an inexistent purity. These evil elites too, like 18th century nationalists, speak of a golden age that did not exist when Scottish lowlanders mooned the English and Roger the Norman kicked some Muslim back-sides. They too invent lines of identity and use them to exclude a hateful other.

This is why reviving national and ethnic identity politics in this day and age is not an innocent anachronism but a dangerous, perhaps even malicious ploy to reach ends that cannot ever be justified unless they are founded on myths and slanders.