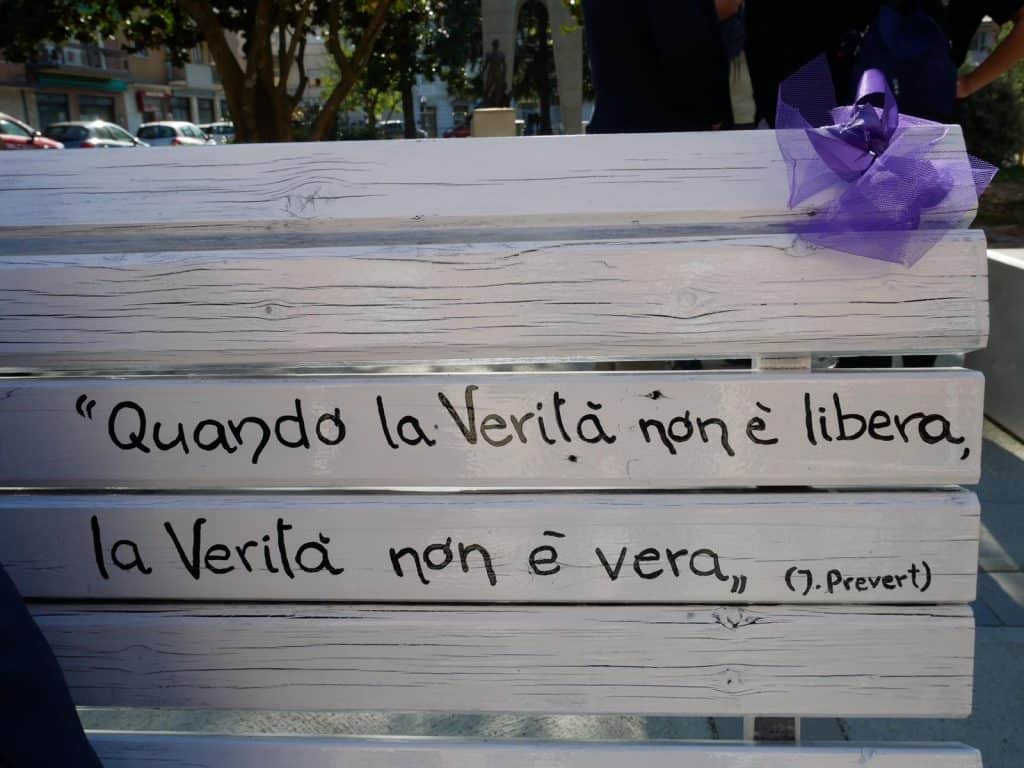

Luca Perrino, president of Leali delle Notizie, unveiling Ronchi’s new Freedom Bench in the town’s main square yesterday.

Ronchi dei Legionari is a provincial town the size of Żurrieq. It is home to an NGO that has about 50 signed up members called ‘Leali delle Notizie’ (loyal to the news) that got a small office from the local council from which to conduct its activities – exhibitions, meetings, readings and music nights – under the broad heading of supporting journalists. It is run by Luca Perrino a local hack who writes for the regional paper who has more energy than most people.

Every year in June they host a 10-day festival bringing journalists from all over the country to talk about their work.

A few days after Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed they sent an email to her son Matthew not entirely hoping to get an answer. They expressed their support and asked if his family would mind if as of the following year their festival would be permitted to award journalists for their courage with a prize named after Daphne. To their surprise they got an answer. The award has since been awarded twice.

Its second awardee was Sandro Ruotolo a veteran Italian journalist who lives under armed escort and is driven around in bullet-proof cars because of threats from the crime syndicates of his native Naples.

Ronchi’s award brought him close to the story of Daphne Caruana Galizia that would have been saved by the protection he and 22 other Italian colleagues suffer under. It is one thing when the state is on your side against the criminals you report. But Sandro Ruotolo famously reported in his younger days on mafia infiltration in the Italian government. He is not too naïve to imagine how much harder it must be for a journalist reporting on a state aligned with the criminals you are inconveniencing.

The Maltese government is not going to give protection to journalists revealing criminal infiltration within its own ranks. It stands to reason then that people like Sandro Ruotolo and others stand by Maltese journalists and provide them a “media guard” in place of a state “armed guard”. They call it scorta mediatica.

(L to R: Sandro Ruotolo, the author, Matthew Caruana Galizia, Marilena Natale, Paolo Borrometi and Beppe Giulietti, President of the Italian Union of Journalists)

But yesterday’s ceremony went one step further. When the Mayor of Ronchi gave Matthew Caruana Galizia the honorary citizenship of his small town he wasn’t just creating a photo opportunity.

The Mayor explained that Ronchi has not granted honorary citizenship to anyone for more than 2 decades and that was to someone who fought on the frontline. This part of Italy is 16 kilometres from the border with Slovenia. Here the north-eastern limits of Italy were defined in the bloody conflict with Austria-Hungary up to 1919 and the border settlement with Yugoslavia in the aftermath of the second world war.

Here the meaning of being Italian was defined on the cultural frontlines of the first war and the political resistance to fascism and sovietised communism in the second. Ronchi is the burial ground for tens of thousands of the soldiers fighting on either side of those divides. This place is no stranger to heroes.

Sacrario di Redipuglia, Ronchi dei Legionari

In his speech yesterday Mayor Vecchiet reminded therefore what it means to be a citizen. It means to be a warrior for the principles of the anti-fascist constitution of Italy adopted just over 70 years ago. Citizenship is about being a soldier in whatever front one is capable to serve for the constant battle for liberty.

Matthew Caruana Galizia’s front is article 21 of the Italian constitution, its proclamation that all thought can and must be freely expressed through whatever medium without being subjected to authorisation, not to mention censorship, of the state.

That value is not about journalists being free or safe. It is about the right of all citizens to be informed so that they can take informed democratic decisions in the broadest interest possible. A threatened journalist, never mind a dead one, a journalist that cannot speak freely cannot fulfil all citizens’ right to be informed.

A few days I go I wrote a piece reacting to Julia Farrugia’s callous remark that citizenship she sells to people only she is surprised turn out to be crooks would be taken away. I said that is not what citizenship means. But that is a negation, a poor way of defining something.

Mayor Vecchiet, a humble part-time mayor of a humble part-time time provincial town where no building is taller than the village town hall and that stands at just 7 metres, answered the question of what citizenship means.

It is belonging to a community where we all do our bit. We all have rights – fine – but those rights are given life by us fulfilling our duties. Focusing specifically on the democratic right to be informed we recognise that depends on journalists’ duty for honest, committed and courageous reporting, on their protection by law enforcement and justice institutions, on respect towards them by people of power and authority, on the engagement with them by civil society and on the understanding of their function by an educated citizenry.

Granting honorary citizenship to Matthew Caruana Galizia exemplified that civil society’s engagement with journalism and this community’s educated support for the work he and those of his profession do.

That is civilised. It is democratic. It is not without dangers, risks, abusive politicians, failures of an imperfect state made of imperfect, sometimes corrupted, sometimes mafiosi people. But this citizenship is not sold. It is earned, freely. It gives no special access to airport fast lanes or property purchasing rights. But it doesn’t lie about the real identity of its holder. It is never taken away.

It proclaims the citizen’s commitment to all other citizens’ freedoms. This is what citizenship really means.

Photos: Roberta De Maddi