In November 2019, I wrote to Michael Farrugia, then minister for home affairs, asking to visit detention centres operated by the government to detain migrants. He ignored me. He was busy accusing Repubblika activists of sedition at the time. A few weeks later, a new prime minister moved him away and replaced him with Byron Camilleri. I renewed my calls to visit the detention centres as well as the prisons.

There was a context that spurred me to do this. In 2019 migrants were convicted of setting on fire the beds and the facilities they were being kept in. They were being detained in army barracks in Safi and the migrants claimed conditions were unacceptable. They claimed they had no means except arson to make the rest of the country aware of their suffering.

The rebel migrants (and perhaps some innocent bystanders among them, as well) were then hauled to court chained to each other in a scene on Valletta’s Republic Street that would not have been out of place at an 18th-century slave market. From there, they were promptly dispatched to Kordin, stripped naked and hosed down in the courtyard and imprisoned for months in cramped conditions.

From the frying pan…

At the time, the government flatly denied detainees had any cause to complain. I asked to see for myself if what the migrants were saying was true. I protested in court against the government’s refusal to consider my requests and after a joke-tour of pointless corners of the Kordin prison, I took the matter up in a fully-fledged court case.

The court case is still ongoing but after Byron Camilleri was called to testify in the case, something surprising happened. I received, in June 2021, a response to my request from November 2019. I have been at least invited to visit the Safi detention centre.

The detention area is across the road from the main airfield. It is part of a military compound bounded on one side by the aeroplane refitting hangers and by the villages of Safi and Kirkop on the other. As you go in, you step deep inside a remnant of colonial history. Most of the buildings, huts, landscape and layout is heritage, largely untouched, largely unmaintained, left by the last British soldiers who used it forty years ago.

Large military trucks bake in the hot sun alongside corpses of old disused vehicles, their military green paint fading, losing the battle with rust.

The place was eerily quiet. But with temperatures over 40 celsius, the silence matched the harsh desert atmosphere of the scorched earth around the squat colonial buildings.

The guard at the gate directed me to the detention area, the far west of the army compound.

Here the military uniforms, and the buff and trimmed bodies of the AFM guards, gave way to beige polo shirts marked DS, for detention services, worn over paunchier bellies of the detention service guards.

One of them drove me to the DS’s administrative building in a dishevelled car. You’re not in the army now.

The DS’s administrative building, spartan, colonial, would have been a time machine to the 1960s but for the unpainted gypsum boards under the ceilings and the struggling air-conditioning units losing the war with the heat.

The director’s office was on the first floor. Long re-used furniture and the spartan facelessness of an office assigned to a lowly civil servant working on a budget. There I was introduced to the director of the service, one Robert Brincau and with him two younger gentlemen, Kyle Mifsud, the service’s “welfare officer”, and Ryan Spagnol from Minister Byron Camilleri’s office.

The conversation with Brincau, Mifsud and Spagnol started awkwardly enough. I reminded them why I had asked to visit the detention centre in the first place, pretty much what you’ve read so far here. And then I asked the director, Brincau, how he rates living conditions for his detainees.

“Komdi,” he said. Comfortable. Sure, he acknowledged, their movements are restricted. But all their basic needs are covered. ‘We make sure they have the food they want and the clothes they need. And we’re here all the time to field their many questions and to give them the information they crave.’

Before Robert Brincau finished his introduction, the young political apparatchik sitting opposite me at the director’s desk butted in. He anticipated my follow-up question, hearing it before I breathed it. In my head, I asked the director, ‘then why did migrants set fire to their beds in 2019?’

“We have made many changes during the past year,” Ryan Spagnol told me.

If he weren’t reading for a memorised script, he would have said, ‘this is what we have done to avoid a rebellion by human beings so determined not to take their misfortunes lying down that they walked across a desert and took on an ocean aboard rafts.’

Ryan Spagnol was, however, reading from a memorised script: “We have made changes during the past year,” he said, “to achieve a better balance between the needs of security and the welfare of the detainees.”

He then took me through a rundown of initiatives taken over the last 12 months or so. They made an effort to ensure all detainees are kept in decent conditions, tacitly implying they had not been before. Since September of last year, detainees could speak to a welfare officer – he was in the room – and more officers would be recruited to beef up that part of the service. Guards were no longer hired through private contractors. Now detainees were managed by trained in-house staff with a permanent commitment to the job.

The hostile all-black outfit of the guards has been replaced with a more approachable tan. When he mentioned that, I remembered noticing the uniforms. In contrast with the sharp and tough AFM guards, they seemed informal, even somewhat throwaway. But it made sense now. This was intentional. It was a process of humanisation as well.

The list of changes and improvements rattled on from Ryan Spagnol’s lips like a well-rehearsed presentation. The dormitory that was set on fire in 2019? That was being refurbished and refitted. In the meantime, dormitories set up in temporary tents have been knocked down and replaced by brand new stone and mortar blocks. The new blocks increase capacity, which means less over-crowding.

Less over-crowding allows administrators to avoid forcing together in compressed, desperate conditions people from countries, tribes, and cultures too loaded with prejudice and intuitive mutual dislike. Some examples were thrown at me. West and East Africans. North and South Sudanese. Timid, short Bangladeshis, and flamboyant, muscular, spectacularly strong Africans. Four Nigerians and thirty Bangladeshis in the common room and the TV stays on Nigerian TV.

A better-organised camp allows group needs to be heard and addressed. Bangladeshis dreaded breakfast, lunch and dinner as wheat was likely to feature in any serving, followed by the pains of a digestive system brought up on rice. If you listen long enough and well enough, switching a hot dog with a chicken curry doesn’t change much in the grand scheme of things.

All courtyards have now been secured so that detainees can have access to outdoor space at any time of the day. During Ramadan, at night as well.

Every detainee now has 24-hour access to a phone to call home, and groups of migrants can share TVs to escape the drudgery and boredom of detention and think of home or watch the football.

Upon arrival on a boat, migrants no longer depend on charity for underwear and clothing. Clothes are now part of their welcome package, and stocks of replacement outfits are kept to make sure their human dignity is respected at all times. The only charity that is still welcome by the detention service is the donation of books. Donated books are kept in storage until there are enough to give one to everyone. Everyone wants a book if anyone gets one.

The general message, Ryan Spagnol told me, was that detainees had basic needs that the service was now better equipped to consider and help out with. Until last year, most of the detainees could never get a turn to call home. Many of them were frustrated to the point of madness for not being able to tell their loved ones they had survived the Mediterranean crossing.

It is incredible that anyone before now could not have realised this and frantically tried to do something about it.

I asked Ryan Spagnol a question no political appointee could answer. “Would you say the riots of 2019 were caused by the authorities’ neglect of these basic needs?” You know, access to open space, phone home, clothes, food that did not hurt? In a fit of sympathy with Ryan Spagnol, as I saw him squirm in awkwardness, I reworded the question in a way he could answer. Perhaps I saw in him the well-meaning misunderstood political commissar I was 15 years ago.

Perhaps if I had met in that room another crazed tyrant, a fascist and sadistic megalomaniac like I had met Alex Dalli when I visited the prison last year, this piece would make for more entertaining reading. But instead, I met three public servants with a job to do and a determination to do it rigorously and compassionately.

I don’t want to sound surprised that I was impressed by the professionalism and correctness of a political commissar working in a government ministry and handpicked for the job as a person of trust. Because surprise suggests that I assume that every person of trust is trusted purely for their partisan loyalties without regard to their other qualities. Almost always, that is not an unreasonable assumption. And that’s seriously problematic when choosing partisan loyalty over professional competence ends up costing human lives.

“Would you say these changes will help avoid future riots?” I asked instead. Perhaps because he appreciated the fact that I had unwound the trap, Ryan Spagnol let rip.

“I reject the accusation that there had been systematic neglect here,” referring to remarks made by the Council of Europe’s Committee to Prevent Torture (CPT). “But we have learnt much,” he went on. “We communicate more with detainees. We try to anticipate their needs.” And pointing rather dramatically at the director of the place, who sat silently through most of the conversation, Ryan Spagnol told me “their job is no longer just preventing the escape of the detainees.”

There was a clearer picture of what he had meant when he said he aimed for a better balance between security and welfare. It wasn’t just about making sure migrants do not escape onto our streets like wild animals out of a zoo. It was about the dignity they would be kept in, while inside.

Having pushed back on the CPT’s description of “systematic neglect”, Ryan Spagnol told me of the changes he worked on to comply with the CPT’s recommendations. The horrible Lister Barracks were now shut down and were being refurbished to be used in case a rush of migrants needed more lock-up space. But Safi, Brincau explained, presently held some 270 inmates and would not overflow before it was asked to accommodate 980.

Safi now had a 24-hour clinic with doctors on site all the time. The clinic is in a new purpose-built building and has some specialist equipment to reduce the need to parade detainees who have committed no crime handcuffed in community clinics just because of a stomach ache or a scheduled eye test.

As he addressed the recommendations made by the CPT, Spagnol clarified that now use of force has been reduced to the last resort. The last time force was resorted to was September 2020. There had been no violent incidents since.

Ryan Spagnol refers to allegations of torture and electrocution that I had reported on, while I waited to be allowed to visit the detention centre. He dismissed the allegations as unlikely.

But even so, following pressure from the CPT, changes were made to the disciplinary regime that would reduce the risk of abuse and physical harm to detainees. Truncheons and pepper spray cans have been taken away from the guards’ uniforms and are now kept in storage just in case. And any disciplinary breach is now recorded on a register to facilitate investigations of wrongdoing and abuse.

Then the director, Robert Brincau, got up off his chair and brought some trinkets out of his display case. They were small sculptures of animals and toys made for him by migrants out of toilet paper, glue and coffee. One of the sculptors gifted him a knife made of paper and coffee. Gifting a knife, in some cultures, is a show of genuine respect. Director Brincau was, understandably, beaming with pride.

Did the management of this institution really earn their wards’ respect? It was hard to believe. This wasn’t the civil prison. Here no one could be expected to admit to themselves that they deserved their fate. Their only ‘crime’ was to seek a decent life for themselves and to be able to send money they could never earn by staying at home, to their suffering families in their country.

Sure, they had no documents and their means of travel was irregular. But no regular option was available to them.

Each one of them was a Jean Valjean. Unable to feed themselves or their children bread they could buy, they stole some. And they were now holed up for it, in a prison in all but name.

How could people so strong in their determination to better their lot, so frustrated by the hardness of the metal bars that were preventing them, respect their jailors?

As the tour of the grounds now started, it would be impossible for me to judge the feelings of the migrants that I saw. Even so, there was much in the narrative that Brincau, Spagnol, and the earnest young welfare officer Kyle Mifsud, that was corroborated by what I was to be shown.

In the first block, we approached half a dozen North African men in their 20s and 30s hovered to the steel grating opposite us like caged animals at feeding time. They did not seem hungry for food. But they had a hundred questions for their jailors whom they called “boss”. They spoke in corrupted Maltese, as North Africans who have spent enough time in Malta are often able to do.

Their questions were urgent, pained, frustrated, sometimes angry.

None of this surprised me at first. Most of them were asking if there had been any response from their home countries about the paperwork they needed, to be allowed out of this prison and on to a repatriation flight home. One of them repeated in broken Maltese, “all I want is to go back to my country”.

The bit that surprised me was that questions were also being thrown at Ryan Spagnol, the minister’s political commissar. It wasn’t just the jail staff. It was him as well. The detainees seemed to know him. In between the calls from behind the grating and his assurance that he would momentarily return to speak to them, Spagnol told me individual stories of the men in the cage.

“That one is the only Algerian we have,” he told me. The Algerian authorities are being annoying with pretend covid procedures while that man is stuck in here for no real reason. There were a few other stories like that which Spagnol knew and he told me about. Stories of people.

I could see that though the man was hired to drive policy, to administer detention as a deterrent, and to send back to their countries all migrants that he possibly could whether they liked it or not, he still considered the cases he handled as people, individuals with stories of genuine suffering that even if he probably could not ease he was determined to avoid making much worse.

I detest the policy of detention in the management of migrants. However clean the clothes, and large the TVs, and digestible the food, locking people up for wanting a better life is in and of itself a dehumanising policy. I know the administrators of the Safi detention centre do not agree with me on this. But I respect the way they go about their job.

They showed me around the rest of the grounds. I went inside the control room for a view of the CCTV monitors. That was another surprise for me. The last time I was on one of these tours, I was being taken around Kordin by General Buck Turgidson and there would have been no way he would let me see the big board.

I was then taken to see two new detention blocks, completed, secured, but empty, never used, kept as excess capacity in case more migrants were brought in. These new blocks replaced the old tents. I have never seen the old tents, but the unacknowledged and unspoken admission of the officials taking me around was that the tents had been miserable and unsuitable for human use.

On the inside, the empty jail blocks looked to me to be, at best, the very minimum of what would be acceptable for humans. Consider the ‘dormitory’. It was still an empty room, unequipped with beds or any furniture so far. I measured the space using my stride, stepping what I estimate to be 10 metres the length of the room and 4 metres its width. There were two ceiling fans and automatic fire sprinklers. There were four windows, around 2 metres above the ground, openings of around 1 metre by 50 centimetres. Barred.

When I asked, I was told the room would accommodate a maximum of 20 people: around 2 square metres per person. My calculations are necessarily approximate but not promising. Most migrants are kept in detention for up to a year. Some might be held for up to 18 months. For a space that had been planned from scratch for such drawn-out requirements, it didn’t feel to me like it met the modest aspiration of the balance between security and welfare.

Next to the dormitory was the shower and toilet combining Turkish toilets dug out of the ground with a hand-held shower head. You wash where you shit. There were 8 cubicles to be shared between 2 dormitories of 20 detainees each.

In place of water sinks, there was a concrete structure to hold water from a row of half a dozen faucets. Conventional sinks (and Western toilets) tended to be stood upon, I was told, and broken too soon. These solutions were more permanent.

I was shown the stores next. There were stacks of tracksuits, underwear, digestible shower soap (intended to avoid self-harm), crocs, and 55” UHD TVs. The guy who manned the store saw me smile at all the TVs. “Believe me,” he said, “we’d rather run out of toothpaste than run out of replacement TVs.”

I could see why at our next stop. They took me to the only other occupied jail block at the detention facility. This was where the detained Bangladeshis were living. I had asked the director to be taken inside a cell block to get a close look at facilities in use. And I was. I stepped inside the guards’ cage in the detainees’ common room. Around 50 people were seated in a refractory of long tables, their backs towards me silently watching South Asian music videos on a loud TV.

A man was to my left crouched on a rug on the floor speaking softly what I presume was Bangla over a fixed-line phone. Over the din of the sitar and esraj coming from the TV, Ryan Spagnol explained to me how the voluntary return scheme they try to sell the migrants works. The EU gives volunteers a ticket home and €2,000 in cash to start a life in the hellhole they left in the first place.

The scheme doesn’t work for everyone. Some that are ineligible for it are offered €500 by the Maltese authorities instead. And some take the scheme on the back of a nudge and a wink that once back to their country of origin their fresh application to come back to Malta legally might be reconsidered.

Sometimes it is indeed reconsidered, I was told. And I gaped at the futility of it all. As I looked up from an explanation that had been shouted in my ear and saw that most of the Bangladeshis who had their back to me when I got there had now turned around. They crowded around the steel grating that kept us apart, keeping a respectful distance, but looking at me, curiously, unsmiling, wary, perhaps hoping that I was the bearer of some news.

Or perhaps that was their way, behind cultural barriers and language differences, to express their irritation that I had come to observe them, I can’t help thinking, like attractions in a zoo. From their side, this fat man in shorts, on the wrong side of the bars that kept them inside, must have been a rare, curious, moderately offensive attraction.

There is, of course, something which is worse than detention, especially if it is for several months, in uncertainty and in apparent retribution for living up to the most basic human need, to improve one’s condition. And what’s worse is detention in filthy, cruel, violent conditions.

Whatever there had been in 2019, I did not witness filth, cruelty or violence during my visit yesterday. I saw instead guards, wardens, directors and a political apparatchik, wielding a cruel policy without cruelty. Even, I must say, with a touch of pity and kindness.

Ryan Spagnol told me he hoped the detention service could be taken out of the military compound and a dedicated facility is erected to accommodate migrants in detention. The implication there was that this young politician realised what his elders still refused to acknowledge: that migration was not a temporary phenomenon that could be wished away. And that the country needed to treat even the most unwanted decently and in a civilian – not a militarized – environment.

I saw that since 2019 the Council of Europe’s pressure had forced the authorities to reverse neglect and restrain sadism. And I saw that insisting repeatedly to be allowed to see facilities the government would rather hide, helped force the government to clean them up before, inevitably, some court would order them to let me in.

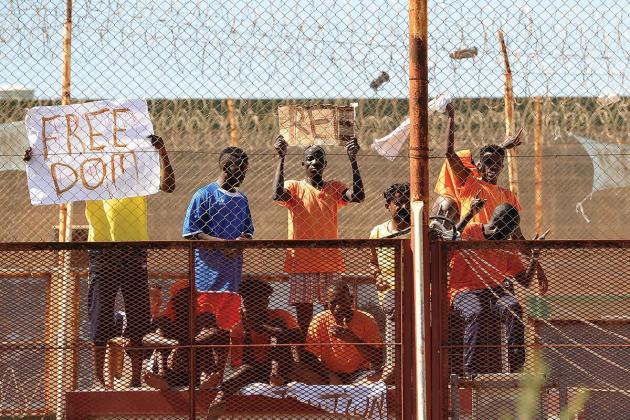

But then I also saw the pain, shouted aloud by the agitated North Africans, or stared quietly by the painfully patient Bangladeshis, or exerted on the kicked around, MFA-supplied footballs by the tall West Africans unable to find release for their boundless power and energy. I saw men whose only hope in life had been to be free. And I saw them trapped behind metal bars, through the thick obstruction of thick steel grating, from the inside looking out.

They were looking out to my world and the life I drove back out to after my three-hour, 25 cents tour, of their clean and polite, temporary hell.