For those of us of a certain age, who grew up watching Italian television, the Capaci and subsequently the via D’Amelio bombings in 1992 that killed anti-Mafia judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino loomed large in our psyche. They were events that shook us and glued us to our television sets long before the emergence of the 24-hour news cycle.

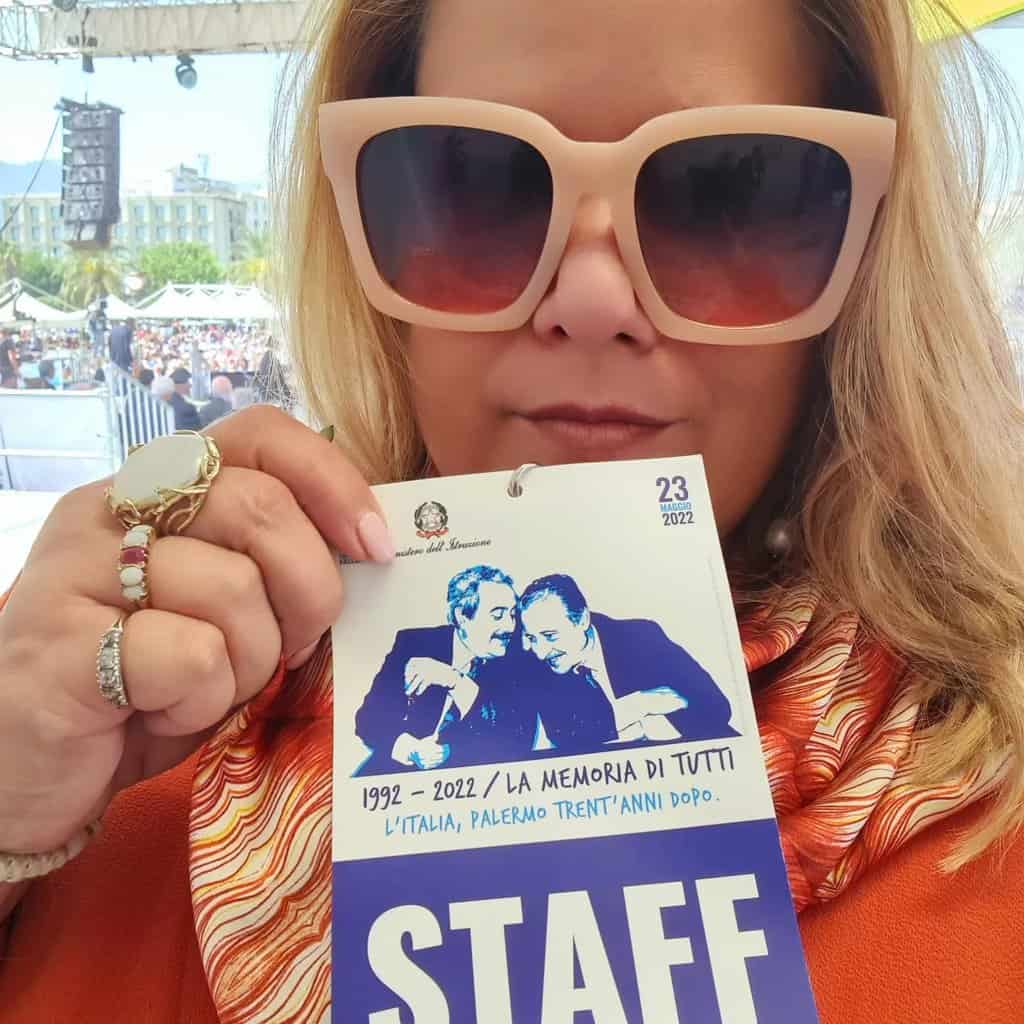

So when Repubblika was invited by the Fondazione Giovanni Falcone to take part in the official commemoration in Palermo of the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Giovanni Falcone, his wife Francesca Morvillo, herself also a magistrate, and their bodyguards Rocco Dicillo, Antonio Montinaro and Vito Schifani, I knew that it would significant but I wasn’t prepared for the emotional punches it packed over and over. Most of you have maybe followed my social media posts, and also those by the Repubblika president, Robert Aquilina so some of what I will write will not be totally new.

Our first stop was in Capaci, 18 km from Palermo. On the 23 May 1992, Giovanni Falcone’s plane landed in the small airport of Punta Raisi. Members of the Corleonese Mafia were alerted and the lookout high on a hill overlooking the A29 autostrada, Giovanni Brusca, pressed the button that detonated the massive bomb that killed the anti-mafia judge and his entourage.

If you watch film clips of the era, you will see a small white building that marks the spot from where Brusca and an associate lay in wait for Falcone. The words ‘No Mafia’ were painted on the building soon after the bombing. The slogan has become an icon and a visible commitment of civil society against the violence and the culture of death and illegality of the mafia. With the passage of time, the words faded. On Saturday, 21 May in the afternoon, a group of children and young people from the area were tasked with refreshing the lettering with a lick of paint. Before each letter was painted over, a message was read out. Repubblika had a turn too. Its president, Robert Aquilina made a short address and painted over the letter F.

The walk up the hill was strenuous, to say the least. The view from the top is magnificent.

It reminded me of another hill closer to home. Another magnificent view. Another beauty spot forever marred by a heinous crime: the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia in Bidnija. On the hill in Capaci, I looked out from the spot where the assassins lay in wait for Falcone and saw an expanse of shimmering sea and I thought to myself: How can a place so gorgeous be so ugly at the same time? If you follow my social media, you know that I often made the same observation when I visit the spot where Daphne’s car came to rest after the powerful blast that killed her.

There were scores of children and young people in Capaci, all wearing t-shirts emblazoned with ‘No Mafia’. They carried posters and spoke the name of Giovanni Falcone with pride.

Daphne was also called a hero in the Public Inquiry report. No children and no young people in Malta march in her name, demanding justice. At least they haven’t done this in years.

On the hill in Capaci, I could see some of these parents weren’t even born in 1992 or were very young themselves but I could see them walking with their children in Capaci pointing out the place to their children where Falcone was killed, telling them that he was a hero.

I could also see them two days later in Palermo, scores and scores of them marching towards the Foro Italico where the official commemoration was held in the presence of the President of Italy, Sergio Mattarella and other personalities from the judicial, political, educational arenas and most importantly for our perspective, civil society. I can hear you say: but they had thirty years to get where they are now. Yes and no.

Something that Mattarella said at the Foro Italico deeply resonated with me. “Thirty years have passed since that terrible May 23 when the history of our Republic seemed to stop, as if annihilated by pain and fear… The deafening silence after a boom, the likes of which had never been heard before, effectively portrays the disorientation the country when faced with that unprecedented attack… civil society refused to accept the humiliation of the country in silence and contributed immediately to society’s renewal.”

It was as if he was speaking about us, about Malta four and a half years ago. But this is where the comparison stops. Whereas 30 years ago, institutions in Italy leapt to the defence of democracy that was dealt a mortal wound, here in Malta institutions are captured by the very mafia that killed Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Well-meaning friends tell us that we are wasting our time fighting this hydra that has killed our compatriot and is suffocating our society. But I have dreams for my country. One day, I want to sit in a public park with the chatter of the children around me to hear the President of our Republic commemorate Daphne’s life’s work and legacy. I want to hear him or her call Daphne a hero. I want him or her to denounce the State that killed her and congratulate the police for finally doing their duty.

But this is impossible, I hear you say. Yes, if the people remain silent, afraid, complicit.

We, the people should be a living, breathing alternative to the mafia’s culture of corruption and death. Not my words. But the words of the heroic anti-mafia mayor of Palermo, Leoluca Orlando, who welcomed us as friends, who sees in us what his city was thirty years ago, who works from the very desk where a predecessor was the mayor and the head of the mafia all at once. He told us that he chooses to use the same desk as a symbol that leadership can change, only if the people demand it.

‘Never stop speaking’, he told us earnestly during our meeting, ‘for the mafia loves silence.’ These words reminded me of the message he had passed on to us nearly three years ago at the second anniversary commemorations for Daphne: “Please, tell the story of Daphne to everybody to let the people understand what happened in Malta. Don’t remain silent. Speak, see, hear, and if necessary, cry.”

That’s the plan.

In a now famous interview given to Marcelle Padovani in 1988, Falcone was asked: ‘What idea of a state are you fighting for?’ He replied that he is actually fighting for a society where the state is nothing more than its tangible expression. The interviewer persisted: So, are you fighting for this kind of society? ‘Yes’, he replied, ‘a society that we all want where the mafia should not exist.”

This is what Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino, Daphne Caruana Galizia and other heroes fought for. And they paid with their lives. We must continue fighting for the society they died protecting.

Capaci and Bidnija are two theatres of destruction, of death, of loss. They are places of immolation. But we cannot stop there. We don’t celebrate heroes because they died, or how they were killed. Rather we recognize that they were killed because how they lived. With courage.

Heroes never die. They live in our will to fight for justice.

They live in our will to remember them.

They live in the future we wish for our children.