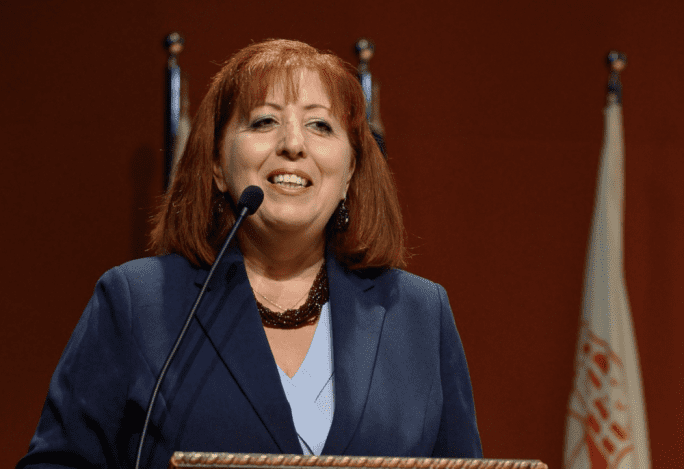

Sometimes I feel this country has its ankle stuck to a time machine that keeps warping it back to the days of King John of England. Professor Carmen Sammut, the University’s number 2, told the Commissioner for Education in the Ombudsman’s Office nobody has the power and authority to examine what the University decides in academic matters.

She quotes the principle of academic autonomy which is part of the law that sets up the University. Before I begin to think about why she said this, I want to point out why academic autonomy is a thing. Universities are the place where ideas are studied, debated, examined, and, eventually expounded. Those ideas must be processed through scientific rigour and the truth of their findings cannot be impacted by whether that truth is convenient to people in power.

If the university is, say, researching poverty and its sociological implications, no government ministers can interfere to stop that research to avoid the findings causing them political embarrassment. Similarly if the university is researching the inequalities suffered by women, no church can block the findings because they are inconvenient to their male-dominating Weltanschauung.

Free universities are essential to democracies. Their autonomy is a safeguard against tyranny. In other words, it is another layer of protection from governments that bend the truth to rule over us.

Professor Carmen Sammut did not cite academic autonomy when defending university from some encroachment by the government. Instead, she threw the book at an ombudsman who was reporting on his findings after a student complained they had been treated unfairly by the University.

In brief, the case concerns a student who wrote their dissertation on a subject two of their three examiners knew close to nothing about. The ombudsman for education (Vincent De Gaetano) did not evaluate whether the mark the student got had been fair. Presumably the ombudsman was even less of an expert in the subject matter, than the academics. The ombudsman is not an exam grade revisor or an external examiner. The ombudsman did however find that no one can be given a fair grade by any examiner who knows next to nothing about the subject they’re examining.

Vincent De Gaetano suggested the university gives the student another, competent, board of examiners and rate their work afresh. The university told the ombudsman they wouldn’t do what he suggested because the law says they’re autonomous and no one can interfere.

Bloody hell. Academic autonomy is there to protect academics (and students) from government interference. It isn’t there to give academics immunity from review. Academics should be free, but no one suggests they’re infallible. Indeed, Vincent De Gaetano, in his letter to Carmen Sammut, and in a fit of acid sarcasm, made the comparison with papal infallibility, where ex cathedra someone seriously believes themselves incapable of being wrong.

Academics must be free, but they can also be wrong, and they should fix their mistakes like everybody else.

It perhaps is not surprising that this warped feudalistic logic was used by Carmen Sammut. I wouldn’t be shocked out of my wits if I were to learn Carmen Sammut’s letter turned out to have been based on the advice of the University’s lawyer du jour Robert Musumeci who has been arguing recently that the fact that the law excludes judicial review of actions by the President when acting on their duty, means that somehow the President is above the law.

Someone made a good point to me recently after I wrote about that. The President hands out warrants to lawyers. If the President unilaterally decided not to sign Robert Musumeci’s warrant even though he’s so demonstrably eligible to it, would Robert Musumeci have accepted that decision as an unimpeachable, supra-legal, act of a lesser god?

There’s a growing culture of government appointees crowning themselves as pocket size popes. They run prisons, planning agencies, identity processing departments, and now even universities, like their personal fiefdoms where their word is law.

Carmen Sammut too has now asserted not merely academic autonomy but the right of the University (while she runs it) to treat students unfairly, to apply administrative processes in a way that discriminates or mistreats people at the mercy of academics’ powers to decide.

If she’s right, Carmen Sammut could claim academic autonomy as an insurmountable defence of decisions like banning women from the Engineering Faculty, or requiring certification in Mandarin to join the Theology program, or even simply failing a student because they rejected a lecturer’s sexual advances or because they don’t like their political views. And no one is entitled to complain outside the academic community however motivated that community might be to protect its own and its collective reputation.

That is manifestly not the intention of the law when it gives autonomy to academics. The intention of the law is to protect academics from political interference. It was never put there to relieve them of the fundamental obligation of doing the right thing.

What’s more, with this response Carmen Sammut and the University have denied students (and, ironically, academics too, because they might all come to need it at some point) recourse to the ombudsman or, quite frankly, anyone outside the university’s administration in situations where they feel the University has been unfair with them. She used an element of the law that is meant to make universities free in order to clip the basic freedoms of students and academics by denying them recourse to the ombudsman.

I haven’t been president for the student union for 24 years and I never presumed to give unsolicited advice to any one of my successors. I’ll make an exception for this one. Don’t take this lying down.