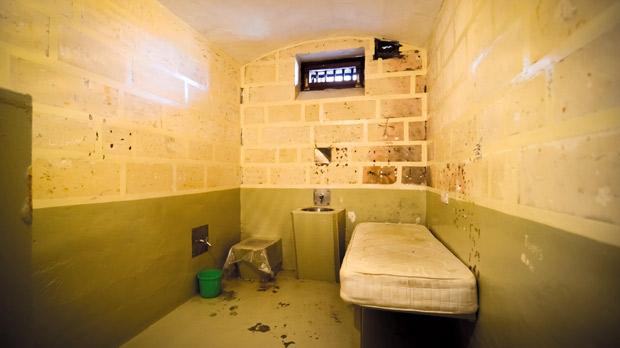

Photo: Ian Pace. (The Times of Malta 06.11.2013: Sneaking a peak behind the prison walls)

I have filed a request with the home affairs minister to visit the prisons and other detention facilities on the island. I didn’t do it once. I wrote to Minister Michael Farrugia (who was the responsible minister at the time) on 12 November, on 13 November, on 14 November, on 15 November, on 18 November and on 20 November.

I focused at the time on conditions faced by migrants after scores of migrants were sentenced to serve time in prison after being convicted of the riots in the Ħal Far centre. The causes of the riots were the conditions at Ħal Far which merited inspection. But if that was cause for rioting, NGOs were reporting that from the frying pan of Ħal Far migrants were being dragged to the fire of Kordin.

My request to the Minister to allow me to visit the prisons followed a call made by NGOs who work with migrants for an inquiry into allegations that “a number of migrants were manhandled, packed like sardines in a cell, locked up all day and humiliated.”

Authorities of course denied mistreatment at Kordin.

As I did my research speaking to sources who work or worked in prison and who have a close understanding of what goes on behind the gates it became clear to me that the treatment migrants allegedly received as a welcome to the prison was representative of an general environment of brutality in the prisons which is not reserved for foreigners born outside Malta alone.

I came to the stark realisation that the fact that 6 prisoners died by suicide or in poorly explained circumstances in the space of 18 months, a rate of deaths which is unprecedented and as far as I could ascertain incomparable to anything in a European prison, is an indication of underlying problems in the custody of prisoners.

There’s a lesson in journalism that says that it is not a journalist’s job to report that someone is saying it is raining and that someone else is saying it is not. The business of journalism is going outside to check the weather for oneself and then report on it.

But going to report from inside prison and other detention areas to assess the government’s compliance with human rights norms and its own laws is not as easy as stepping outside to check the weather.

That is what started my series of requests to Minister Michael Farrugia to visit the prisons and detention centres.

I told him: “As you are aware, allegations have been made on multiple occasions that the conditions in which immigrants are detained or hosted are unsuitable and possibly falling short of basic standards of decency, if not basic requirements of their fundamental rights. Also, allegations have been made that migrants that have been moved to the Kordin prisons after the riots of a few weeks ago are now kept in unsuitable conditions including overcrowding.

“You may be aware that I am a journalist writing on manueldelia.com, on The Sunday Times of Malta and on other media. In view of this, I am asking for your permission to be granted access within reasonable conditions to the places where migrants are hosted, or held, or detained or imprisoned.

“I will need to be able to take photographs during my visit — obviously respecting the privacy of any inmates — and will need to see sleeping quarters, recreational areas, toilet and showering facilities, kitchens and so on to be able to make a proper assessment of the conditions in which prisoners are kept. I will also need to be able to speak to inmates and staff that are willing to speak to me. Kindly consider this request as urgent.”

Michael Farrugia did not consider my request as urgent. On the 20 November Michael Farrugia got a staffer of his to send me a short note hoping it would stop me flooding his mailbox. She said “please send your request to the specified entities”.

That’s some classic bullshit there.

I had of course checked the law before writing to the minister for home affairs. So, on the same day I wrote back to Michael Farrugia’s staffer: “In as far as the prison is concerned Regulation 66(1) of SL 260.03 explicitly makes Minister Farrugia the responsible entity. There is nothing specific about the migrants’ detention centre but since he’s the Minister responsible for them he will need to tell me to whom he has delegated the authority of permitting access to them. Your Minister has the responsibility here and I will not take well to being sent nowhere in particular as long as it is away from him. Please consider this the sixth reminder to the Minister, whom I am copying.”

After that, silence. By now, 20 November, the government was creaking on the edge of collapse and Michael Farrugia was more concerned with the “violent” protests in the streets of Valletta than with my request for a visit to the prisons. He probably would have liked me to go to Kordin but not in the way I would have had in mind.

I decided to wait for the new government to come in and started bothering Minister Byron Camilleri after giving him some time to find his feet in his new office. I wrote to Bryon Camilleri on 5 February and in his bullet-dodging reply he was slightly more specific than his predecessor.

The minister, writing to me directly which is an improvement on the rotten behaviour of his predecessor, told me to “kindly send your request to the Director of Prisons in so far as the correctional facility is concerned and to the Head Detention Services or the Principal Immigration Officer in so far as detention centres are concerned.”

I did. And today I got a cryptic response from a junior staffer (something called “Customer Care Co-Ord” as if I was complaining about an error in my electricity bill) that said the following: “Further to your request hereunder regarding the above-captioned, and according to this Ministry, you may wish to note that approvals are generally extended to NGOs, lawyers and agencies primarily.”

Who speaks like that?

It would seem that the author of this missive considered my request unusual. It did not feel like an explicit refusal. Merely that the office did not field too many requests from journalists to tour the prisons perhaps wanting to suggest that they need more time to consider the idea.

There was of course the alternative meaning that the ministry considered me unworthy of making a request to visit the prison because I don’t amount to an NGO, lawyer or agency. What does a journalist need with visiting a prison, right?

I wrote back to the ‘Customer Care Co-ord’: “I am a journalist. I am not seeking to satisfy some idle curiosity. Is your response a definitive refusal?”

She replied: “With reference to your email below, kindly note that at the moment, only lawyers, NGOs and international organisations are being allowed entry into the centres.” That’s a yes and a no. Yes, it’s a definite refusal. No, you can’t visit the prisons.

Why should journalists be allowed to visit prisons and detention centres? Because they are operations of the state that need to be scrutinised like all other functions of the state. Because prisons and detainees are wards of the state in whose care they are being trusted.

Because norms of the protection of human rights are most useful to protect individuals that are most vulnerable and prisoners and detainees, whether they are locked up for arriving to Malta without a passport or because they committed cold blooded murder and are serving a life sentence for it, are indeed extremely vulnerable.

And why should the Maltese prisons be specifically visited by journalists? Because people working there are confidentially speaking about a reign of incompetent terror. There are tales of torture and cruel punishment outside the limits of decency and the law. Firearms are used in prison as a threat to inmates. Doctors and lawyers are denied access to their patients and clients at the whim of a tyrannical administration.

Because there are reports of degrading overcrowding and inhuman conditions. Because fear of violence is used as a tool of control. Because care of the welfare of inmates is reportedly being sacrificed to acts of brutality and sadism.

I have not been able to verify these claims directly but have collected them from multiple and independent sources unaware of each other. I have also seen documentary evidence of arbitrary intervention in the medical care of inmates that may have resulted in deaths.

A journalist’s job is to discover the truth and the state is obliged to allow them to look for it.

There will be the usual right-wing gun-toting bring-back-the-gallows response to this. But human rights are inalienable. We need them that way because if the worst among us are not protected by our society, perfectly innocent victims will get no protection either.

And because our own civilisation and humanity are measured by how we treat our prisoners and detainees and how we remember and retain our humanity when our emotions risk sweeping us to seek the satisfaction of violence or at best looking the other way.

I will not accept this refusal to my request to be allowed to visit the prisons and detention centres.

Now to think of the next steps.