I have been speaking to many international journalists visiting Malta over the past 3 days.

I have spoken to journalists from The Economist, Reuters, Sky, Liberation and other publications and news media who came here to report on the aftermath of the assassination of one they consider their own.

Many of them flew in with an open ticket in full expectation of the sort of political upheavals that followed Capaci, Atocha and similar incidents where popular anger at government incompetence and complicity drove the incumbents out of office in hours.

They are perplexed at the placidity verging on the cold indifference of a nation that seems to be in anything but mourning.

I live in Mqabba and down my parts when anyone, anyone, anyone dies, all social clubs fly their flags half-mast. Our republic ignored the death of its principal journalist like it was the death of a dog.

Our Parliament discussed the incident on an emotional flat line. Nerves flared only when one side blamed the other for the incident and a flutter of concern rushed the chamber in case any of them risked losing petty political points.

The handful of sympathy gatherings were smaller than average weddings and were even more like weddings in that everyone present knew each other as a neighbour, culturally if not physically.

Twelve thousand university students united as one, universally bound and committed, in missing the gathering a handful of their lecturers attempted to organise for them on campus. The world’s press went there expecting angry crowds armed with banners and chains but they photographed a desert of emptiness as students rushed out of class not to miss the beginning of the football match on TV.

Journalists expected to see a prime minister under pressure for his political life. Instead they found him cool as a cucumber, smug and coordinating a press campaign to frame his political rivals for the assassination from which he stood most to benefit.

They came across a crowd funding campaign started on a private initiative and asked for comments under the call to be translated for them. They looked on amazed as people on Facebook, with name and photo ID thought nothing of deriding the campaign listing themselves thereby in what should be a short list of suspects.

They looked in disbelief as I translated for them a statement from an official engaged personally by the prime minister calling for the “cleansing” of a hit list of journalists starting with Daphne Caruana Galizia. As I translated for them how a chairman of a national science agency celebrated on Facebook the death of Daphne Caruana Galizia five weeks before it happened.

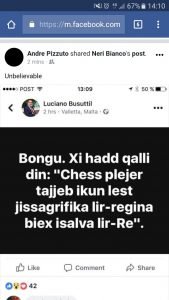

I hadn’t yet seen this product of the obscure genius of Luciano Busuttil, who once called himself a journalist but was than as now a clown.

I had to explain how the live-in partner of the Magistrate who first started the investigation into the killing of Daphne Caruana Galizia, ran an internet campaign headlined #galiziabarra.

A big chunk of the press corps in Malta is on the payroll of the state or of either one of the political parties. They expressed amazement at how it was possible for someone like Daphne Caruana Galizia to do the job she did alone in competition with such corporatist domination.

They could not understand how the great bulk of the nation would rather buy the vilification coming from politicians defending accusations of graft and corruption than the vilified journalist with nothing to gain. Even as the journalist lost her life.

The could not believe as they read a translated statement of the education Minister moving to frame the opposition party even as the crime scene deteriorated and the quality of the evidence was jeopardised by coordinated and malicious delays.

They could not understand how opposition MPs who campaigned against corruption could sit comfortably behind their new leader as he lauded Daphne Caruana Galizia as a national hero in spite of the very fresh memory of his furious bluster against her that fuelled his campaign.

And one of the journalists who spoke to me expressed wide-eyed wonder at how no one seemed to make any remark at how keen Adrian Delia was to withdraw the libel suits instituted against Daphne Caruana Galizia, ostensibly out of human kindness but consequentially no longer having to even attempt a defense against her documented accusations.

They wondered if flowers were so particularly expensive in Malta that those laid in front of her picture in Republic Street over more than 24 hours would have looked oddly sparse in a village wedding.

And I realised as I spoke to these confused journalists that my violent anger at those who killed her beats less overwhelmingly in my chest. Because a greater anger rises at a nation who knows not who was and is on its side. I am angry at all the people missing their own funeral drugged by blind loyalty to those who would rule them and rob them.

At the root of all things Daphne Caruana Galizia did not deserve this. But if we are honest, we did not deserve her either.