Like modern democracy, the reckoning with the race-based caste system came first out of America. The depth of the present crisis is shown by the fact that the debate is not simply about addressing existing inequalities. It is instead searching for their roots in history. It is seeking a reinterpretation of the totems handed down from that history.

The United States still has deeply unresolved issues from the Civil War of the 1860s. The country has not confronted the claim by the southern states that owning slaves is an entitlement for white people. Laws have come a long way. But warriors who fought for the Confederate ‘cause’ are still regarded by some as heroes and shining examples. Equestrian statutes of Confederate generals alone do not force racial prejudice and discrimination to persist. Not directly, anyway. But they are often grounds for rationalising and excusing injustices that accumulate over centuries.

It’s fascinating that outside the United States, many countries are having a heated debate about the racialist totems from their own past. As with every heated debate there is the risk of missing the wood for the trees. Banning ‘The Germans’ from on line archives of Fawlty Towers is just the sort of zeal that corporate types have for not catching themselves behind a curve.

But let’s not let these side shows mislead us from the issue here.

Since we are not really having this debate in Malta, it’s perhaps useful to look at our own totems, the ones we show off proudly to visitors apparently unconscious of their meaning.

The heritage from the Knights of St John is something we often say we are “proud” of. We ignore there is much that we should be aware of that has not aged well.

The Knights were founded in the Crusades, a war of aggression and conquest, unjustified, immoral, cruel, wasteful, oppressive and violent that Europe and the Middle East have not yet come to terms with in ways that makes the American Civil War feel positively superficial and easily resolved.

Generally speaking, even now 900 years after the first invasion of the “Holy Land”, we continue to swallow wholesale the fake news and lying propaganda that started that war. Somehow we do not find the claim that God meant Jerusalem to be Latin and Christian ridiculous. We accept that pilgrims were mistreated before the Crusades which is a pretext with no basis in fact. And we consider the occupation of Palestine as legitimate and God-wished, concerned with religious zeal rather than carving out properties for aristocratic second sons.

We find glory in the long defeat of all the Crusades that follow the first one. We ignore the bloody mass murder of Jews, “heretics” and Byzantines in Crusades gone wrong even by the vile Muslim-hating standards of the early Middle Ages.

The point of the Knights of St John is not that they grew out of this fanatical, religious extremism. It’s that they kept to this perverse logic after the rest of Europe lost interest whether because of intellectual enlightenment or preferring to kill Christian schismatics rather than fight unwinnable wars with Muslims.

It would be a mistake to have a black and white assessment of the two sides, whichever side is which. There were centuries of atrocity, slavery and brutality inflicted by either side on the other.

The Great Siege of 1565, fought on land here, allows many to indulge in an imaginary victim-status, a defence against an aggressive invader, a warmongering perpetrator. That’s one way of looking at things that ignores the fact that the Knights extended their Crusading mission in Jerusalem to piracy and grand theft and larceny, slavery and forced labour. That would make the Great Siege neither a defensive, nor an offensive war, but a front in a centuries-long struggle to define a balance in the Mediterranean.

As much as the Knights justified to themselves the wars in Jerusalem and Accra, they justified Malta and Lepanto as the fulfilment of divine will: a fundamentalist, jingoistic violence willed by God and thrust by the knightly arms of Christian heroes.

We show people around St John’s Co-Cathedral apparently unaware of the vileness of all this. The interior painting over the main door of the church featuring the Cotoners has as its centrepiece an allegorical figure of the Order (now of Malta, in many people’s minds) with turbaned and chained Turks, Berbers and Arabs crushed beneath her feet like the snake at the foot of the apocalyptic virgin.

Nicolas Cotoner’s memorial is particularly egregious with the Muslim and the Negro, chained with their arms tied behind their backs, on their knees where they should be for all to be well with the world.

Before I’m accused of advocating the destruction of these memorials, I should say I would hesitate to argue for the destruction of anything. But these images that are then replicated in the glorifying military style of most of the architecture left by the Knights, are not used as an admonishment for a shameful and immoral logic that has inflicted unnecessary and unjustified death, pain and suffering to generations of people.

Instead we glorify this heritage. We allow it to define us. We use crosses and Crusading colours not as symbols of faith but as warlike symbols of aggression, of a sense of superiority, of a justification of our racist attitudes handed down from above. We allow ourselves to feel that our racial supremacy is the natural order of things.

In that context the cross means different things to different people. For those patriots brandishing as a mark of distinctiveness the cross is as far from the teachings of Christ as the 17th century industrial-scale piracy operated from Malta of the Knights; as far as it can possibly be.

We wave it happily on the rooftops, oblivious of what it represents, insisting that it is our right to express ourselves and to practice our culture and our faith and angrily accusing any suggestion that we may need to reconsider the symbols we use as an attempt to take away from us who we are.

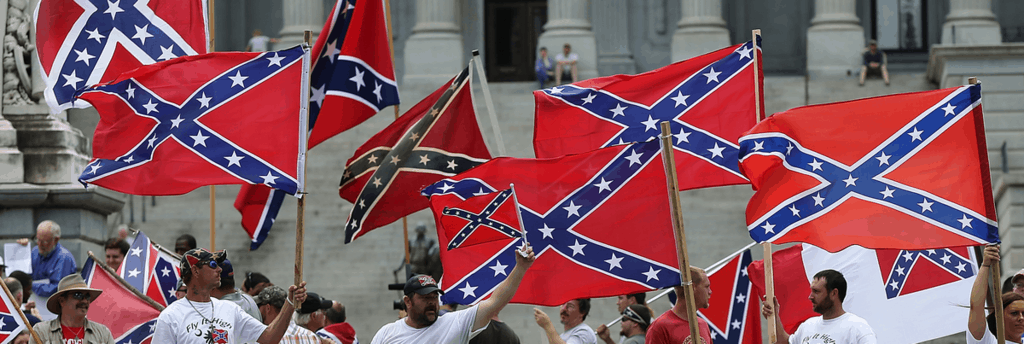

It’s not unlike the use of the Confederate Flag in the southern US states, except older, with deeper set prejudices and more bodies and victims accumulated over time.

For many the idea that we should examine our heritage and confront our history, our own share of shame, the occasions when we have been on the wrong side, is anathema. If anyone of us suggests we should do this, they are traitors. Imagine if people of new minorities living among us were to challenge us to take a fresh look at our Mattia Preti with a critical eye for this historical context which it represents. We’d perceive them as latter day Ottomans here to destroy our way of life.

Just because we’re not having this debate here, does not mean our history does not inspire us to kneel on the necks of people of other races until we squeeze the life out of them, or watch while someone else does it for us.