If a public official, or anyone serving the state and the community with their work, is in any danger it is the duty of the state to protect them. No government minister, no journalist, no judge, no social worker, no divorce attorney, no prosecutor, no teacher, no nurse should be allowed to face physical violence or property damage from vindictive people wanting to harm them or stop them doing their work.

Things can get hairy for people serving the public. Teachers working in tough schools have had close shaves as have many front-line public servants. It can get more complicated further up as well.

I worked for 5 years in the transport ministry, which Michael Portillo had prophetically warned me, more as a reference to himself than out of any interest in my own fate, is most people’s last job in politics. It was mine as it happened.

I never felt in danger myself. But I remember one night when the owners of the old bus operation gathered in Valletta and CCTV footage grabbed a gang of them being shown where the transport minister lived during a middle of the night recce. They didn’t look like they meant to surprise him with cake and champagne. Eventually, that blew over.

But months later a bomb exploded just outside the office of a senior transport official. A consultant who was in the room, meeting the intended target of the bomb – someone I admired very much and worked beyond his retirement age to serve his country with his wisdom, decades of experience and unequalled sense of public duty – lost his legs in the explosion. It was a small miracle that he didn’t lose his life.

Sometimes, the risks of public service are real. No one has suffered a fate worse than Daphne Caruana Galizia’s. But police officers have had their houses bombed, and a prime minister’s advisor was stabbed outside his home, surviving by a combination of sheer will and, if you believe in that sort of thing, divine intervention or bloody good fortune.

I’m saying all this because I want no one to think I’m flippant about personal security for people at risk because of the service they give to their country. When that risks exists, it is the duty of the police, or whatever other security service the state has access to, to protect these public servants.

No one half decent wants anyone in public office, however much they might disagree with them or dislike them, to get hurt because of their work.

The Valletta protests were no threat to any government minister. If they had any justified concerns, that would be about people calling them very loudly eejits, corrupt accomplices, cowards, and harbourers of murderers. They could face chanting and flag waving. But at no point was there any physical threat or risk to them. No one was touched, grazed, scratched, persistently tickled, inappropriately fondled, emphatically embraced or wetly kissed. And there was never a threat that they might be.

Policemen, in reasonable numbers, without ever needing to resort to anti-riot gear or more than their steely presence and gentle touch, attended all protests and never reported any form of trouble. With the exception of one incident when Owen Bonnici’s driver drove over the foot of a police inspector trying to protect the crowd from his congenital stupidity.

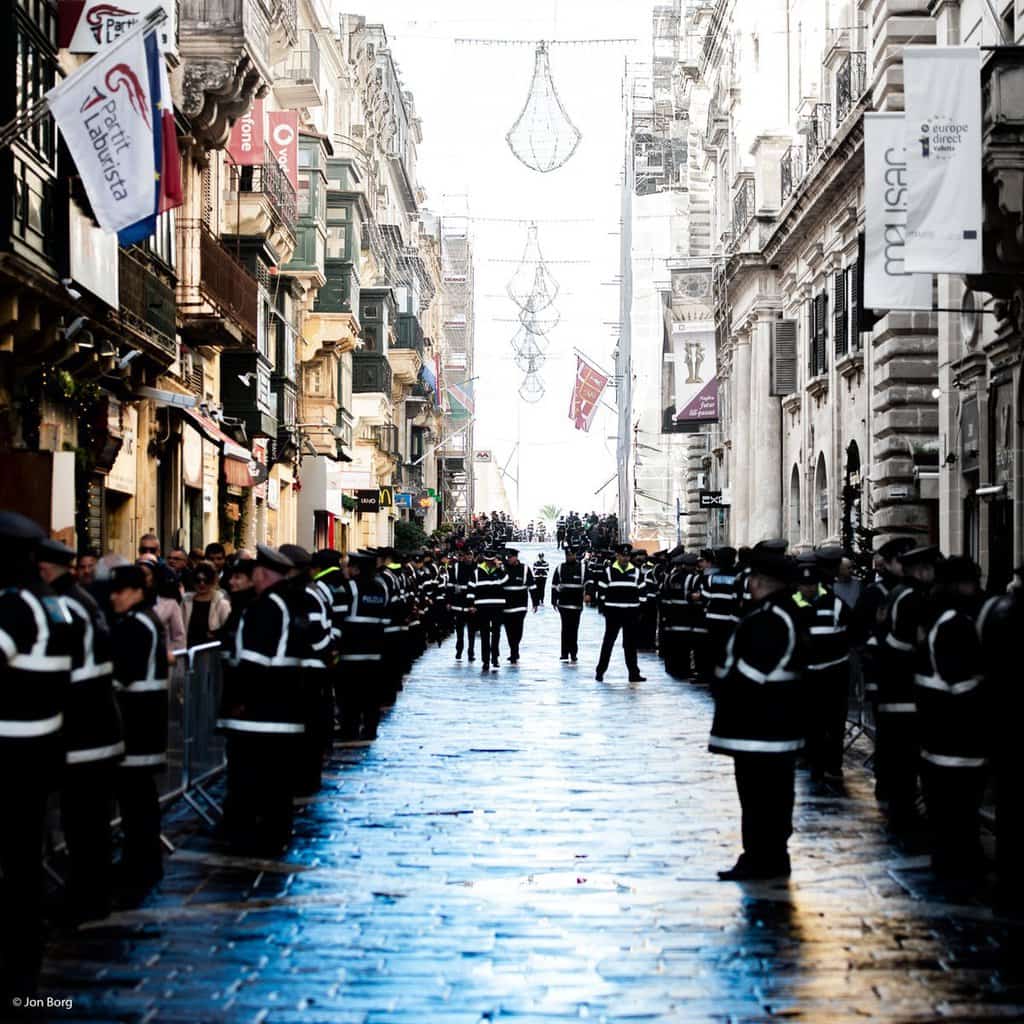

The police were under a lot of political pressure to wheel out the riot gear because the politicians hoped for some violent reaction they could exploit. Police leaders resisted the pressure. They could not resist orders to come out in absurd numbers on Republic Day in Valletta where uniformed police alone outnumbered protesters two-to-one and it’s impossible to estimate how many plainclothes officers were despatched there. The numbers have acquired the status of legend now.

If José Herrera was ever in any danger, the police would have assigned to him personal security. It’s their job and as a government minister he’s well placed to ask for security without having to do much persuading.

That’s not what José Herrera did. He hired private guards instead, like an up and coming hip hop star that shows off his security detail like cars, women, gold chains and wads of cash: status compensators for profound inadequacy.

If José Herrera hired security to look tough while people called his colleagues (no one really mentioned him because the guy is, in his government, as relevant as your pinkie toe nail is vital to the eco-system) that would be funny and ridiculous.

But the man had the gall to send us the bill for his act of childish vanity.

The rules are clear. Expenditure by ministers on themselves is governed by clear rules. A minister can’t wake up one morning and get their office to buy them three cars: the limit is two. They can’t get their office to charter them a private jet: only the prime minister can do that.

Unless the rules provide for specifically authorised personal expenditure, the assumption is it cannot be charged to the government’s account. If it is, as has happened in this case, the minister refunds the irregular expense made and proceeds to resign.

A newspaper report pointed out the expense was made by direct order. Though wrong, that particular infraction is, frankly, secondary. Ministers don’t decide on their own security needs. The police (and other security agencies) get to decide that. And if they say you don’t need security and you still want to walk around with people wearing dark shades and earphones in one ear who talk into their wrist and use a funny codename for you, then you have to pay for that privilege yourself.

What would the code name for José Herrera be, I wonder? ‘Baby Brother’? ‘Long Lunch’? ‘Freeloader Man’?

What Robert Abela meant when he said that good governance would be a priority for his government was that his ministers can wake up one morning and spend money on something the competent government authority for that something has already decided they do not need. And that, only here, is fine.

We’ll pay for his €19,000 private security bill with the can of tuna that guy has stolen to postpone his starvation. Makes sense, right?