I heard a commenter on TV yesterday criticise Donald Trump for being too scared of his supporters to admit to them the simple truth that he had lost the election. He dug up a Winston Churchill quote: “Dictators ride to and fro upon tigers from which they dare not dismount. And the tigers are getting hungry.”

It made me think of our own Lilliputian context. Robert Abela showed remarkable cowardice in his short history as prime minister. He never screwed up the courage to tell his supporters that his predecessor presided over a den of corruption that brought shame and long-lasting harm to the entire country. He never had the courage to say that migration cannot be wished away and that Malta has a moral and legal obligation to rescue people at sea.

And even more remarkably, given how relatively easy the alternative could be, he does not have the courage to tell his people that the climb out of the coronavirus pandemic is still going to be tough and we’ll need to refocus our effort to fight it down before we can say it’s over.

Robert Abela is not to blame for the coronavirus. No one is going to take it against him for leading us through this cautiously and with the level of strictness that there needs to be to prevent more lives being cut short.

But he cannot handle the, entirely understandable, groans of pain from economic operators that have to bear the brunt of restrictions. He does not have the courage of causing displeasure.

What we get instead is this mindless optimism that is truly hazardous. I do not know enough to judge whether the teachers’ union was justified to order its members on strike today. But it is clear that the official advice from the health authorities is no longer widely trusted as objective, based on no other consideration but science, and something we can all rely on whatever we might think of Robert Abela.

The MUT certainly showed that it did not believe what it was being told by the Education Department, that they had the advice of the Health Department that schools can remain open in spite of the unprecedented spike in contagion.

Independently of the MUT, some independent schools and church schools had already made the judgement call to close their doors without waiting for the guidance of the health authorities. That is a damning sign that more agencies in the country are losing confidence in the government’s leadership in the management of the health crisis.

Chris Fearne yesterday said that it was premature to be worried about the contagion spike because perhaps it is only due to Christmas socialisation. If it is only a consequence of too much casual partying over the holidays, the rate of contagion should go down again.

The logic is sound but it demands another logical observation. If irresponsible Christmas socialisation boosted up the numbers of infected, bringing numbers down will require isolating the infected, preventing them from carrying the virus to others.

A short break from physical contact, even the closure of schools, would seem sensible.

I don’t claim to be an epidemiologist, nor, I imagine, does the MUT. But we are endowed with a smidgen of common sense and recognise incoherence when we see it.

The ‘let’s go on as if nothing has happened until we realise something has happened and we could have prevented it from becoming such a mess if we had done something when we first realised’ method is sheer madness.

Especially when one considers that the consequence of this wait-and-see philosophy is more people dying.

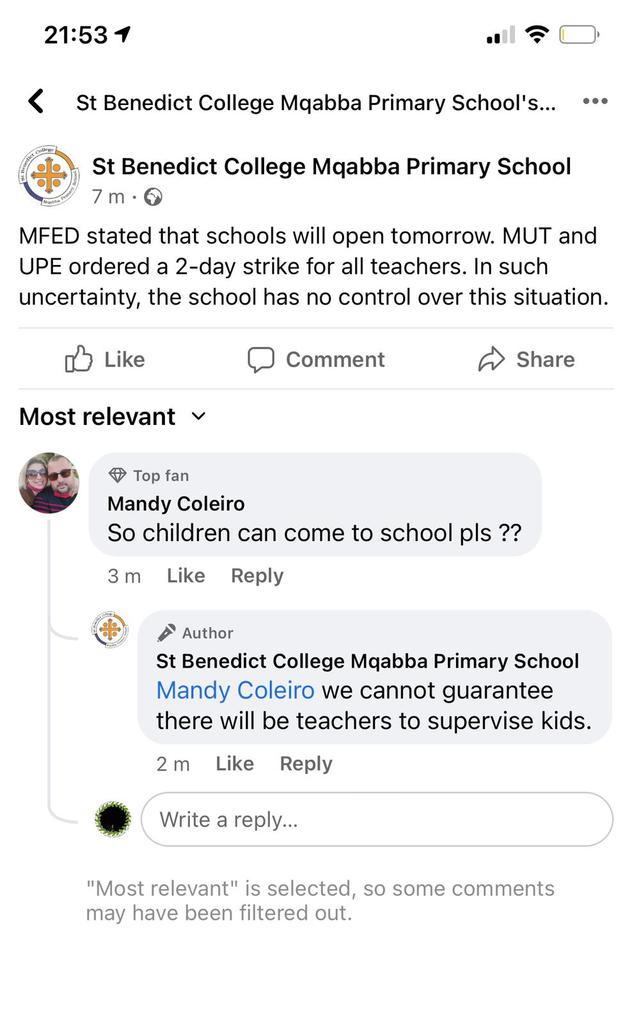

Look at this Facebook post yesterday by the administration of one of the government’s schools.

This doesn’t only show administrative confusion. It shows that the government’s grasp on reality is becoming ever more tenuous, it’s categorical statements of conviction are sounding ever hollower.

This doesn’t only show administrative confusion. It shows that the government’s grasp on reality is becoming ever more tenuous, it’s categorical statements of conviction are sounding ever hollower.

It shows that this time, while governments of neighbouring countries keep their cool and act to slow down contamination, our government is behaving like a gambler on a losing streak. They have decided to squeeze their sphincters until we get herd immunity and hope that the mood of that bright sunrise will make us forget the hundreds of people we are losing to this disease and to their nervous incompetence.

It is a dangerous time indeed when people start relying on their own uninformed judgement on how to deal with the situation because the official advice is so inconsistent and confusing anyway.

The unbridled partying over Christmas did not happen because we are a particularly undisciplined people but because we were given the impression by the prime minister that the coronavirus was already a thing of the past; that it didn’t matter whom we drunkenly smooched under the mistletoe because Robert Abela had already unloaded all the miracle-cure jabs from that private jet.

Robert Abela told us he had defeated the invisible monster, assured us that his unique and exceptional abilities have made Maltese people safer from the virus than any others living anywhere else, gave us a false sense of security, just the sort of fertile ground in which a virus can roam happily.

Right now, we are facing a serious medical emergency that is similar in some ways and different in others from the situation we were in last March. The virus is just as deadly and, perhaps, contagion is even more virulent. But the administration is less scared of the virus now than it was last year. Instead the administration now has more urgent fears: unpopularity, economic stagnation and an electoral backlash. And another huge difference is that there is now a vaccine and therefore a greater promise than we had last year of an eventual emergence from the present darkness.

What a toxic combination.