There was something chilling about how Ian Borg put it when he argued for the need of a metro: ‘If we do nothing our children will curse us’. I don’t think I can ever remember using a quote from Ian Borg as something I felt any sympathy for. Take it out of the specific context of the metro idea and as far away as you can from the conduct of the speaker of those words over the years he was in power, and you’re left with the collective guilt of our generation.

I’ve heard my children speak of me as a “boomer” which if short for “baby-boomer” is about 12 years off the mark. I’m not as old as they think, or I’d like to think I’m not. Reading the EY survey results among people aged less than 30 illustrates the gap they experience.

Consider their judgement of the country we’re handing over to them. It’s a place most of them don’t want to live in. Their primary complaint is the country’s environment which belies the conventional idea that Maltese people are obsessed with cleanliness. We have, near literally, shat where our children are supposed to eat.

The thing about wanting to live elsewhere because the environment in Malta is so fucked up does not merely burst the illusory bubble that the country is some sort of picture book paradise, a picture book with very carefully chosen camera angles to crop out the cranes and the concrete monsters. It’s worse than that. Young people who say they want to leave are implicitly saying they have given up on ever being able to fix things.

From our narrow – boomer, if you like – point of view this is a sign of hopelessness. EY’s commentary is enthused by the finding that so many of the respondents of their survey showed an entrepreneurial streak. More young people than ever speak seriously about wanting to set up their own business. Of course, that’s a good thing. Entrepreneurship is problem-solving, it breathes innovation in and blows stagnation out, it motivates a productive work ethic. All nice.

But let’s be honest. If the positive responses about the entrepreneurial spirit are set against the background of the responses about wanting to move out of the country rather than stay here, it would not be amiss to examine whether there’s a causal relationship between the two responses. Young people who have given up on the country are forced by necessity to fend for themselves. So fair and foul a thing I have not seen.

Entering public life, through activism, politics, public service, journalism, is also entrepreneurship. It is initiative and purpose aimed at the common good rather than personal enrichment. I’m not trying to rank public-spiritedness as normatively superior to profit-driven enterprise. I am however suggesting that when you’ve given up on the idea that your contribution can make any difference to your community you think about what you must then do in your own narrow interest.

Here’s the paradox. It saddens me to think that my generation has caused such harm to the confidence those that follow us should have to make this country a better place. I find the idea that the brightest and the best that are growing up are thinking about leaving a horrific prospect, an abandonment of the legacy that we’ve called our own for generations.

And yet, I’m a father. Much as any parent hopes their children fix what they got wrong, I don’t want mine to be stuck here, feeling helpless, bound by consequences of my failures. I want them to do what’s best for them, live their lives to the full without first having to settle the debts accumulated by my bad choices and the choices of my generation.

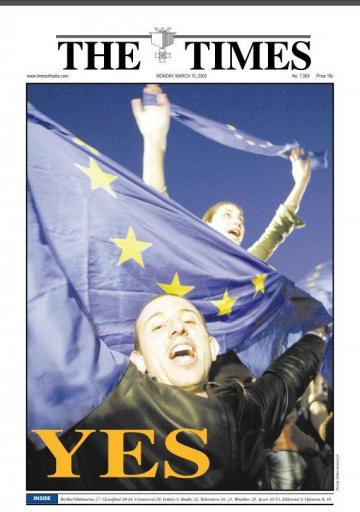

Before the 2003 referendum on EU membership, we were told as campaigners supporting membership to allay fears of older voters at the time that EU membership would encourage young people to leave Malta. It was clear that some parents were prepared to vote against membership for fear of losing their children to “abroad”. Perversely, we found ourselves patiently explaining to these voters that freedom to move elsewhere did not necessarily mean that young people would actually leave. The absolutely great majority of Europeans die in the country where they were born.

I look back at those times and I find that giving our children the keys to Europe, the possibility to just up and go, the right to leave this country if it no longer works for them, as the one thing we got right.

I’m old enough, an honorary boomer even, to find scope for cynicism with any wide-eyed display of hope. Granted that Malta is not the paradise we tell ourselves it is, “abroad” isn’t either. The world is going mad. For many people “moving to Europe” meant the UK, once the beacon of democracy and staunch resistance to nationalist obscurantism. It no longer is that. For others “Europe” was Italy, without the chilling fascist chants of a growing number that is nostalgic for black shirts and street violence. For others “Europe” was France, an any given Sunday political scandal away from the first far-right government since Vichy.

Young people responding to EY’s survey complained about irresponsible environmental management and irreversible harm to the climate causing a crisis that will change, harm, if not destroy life as we know it for centuries after we’re dead. Leaving Malta is unlikely to comfort them wherever they go.

And yet, the take-home note from the EY survey remains that we’ve failed in the one job we rhetorically insist is our purpose in life: to leave our children a country in better shape than it was when we were given it by the generations that came before us.

Whether we do anything now or not, our children are, Ian Borg do please note, already cursing us. They just don’t see the point of sticking around to tell us they are.