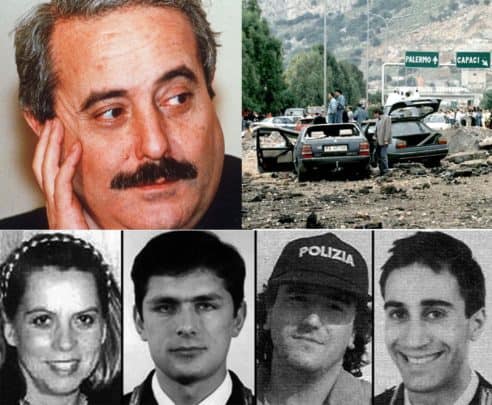

I hope you have been following Repubblika’s social media posts during the visit of my colleagues Robert Aquilina and Alessandra Dee Crespo to Palermo as guests of the organisers of the memorial events marking the 30th anniversary of the assassination of Giovanni Falcone. That day in Capaci the mafia also killed Falcone’s wife Francesca Morvillo and three of his security detail Vito Schifani, Antonio Montinaro and Rocco Dicillo.

I hope you have been following Robert’s and Alessandra’s posts because inevitably the comparisons they draw with the way Daphne Caruana Galizia is remembered here are poignant and quite striking.

Falcone’s assassination and, soon after, the killing of his colleague Paolo Borsellino, did not make Palermo and Sicily a paradise free of problems. But it forced people to take sides for or against the mafia and liberated a society yet enslaved by the pervasive lie that the mafia did not exist.

The Italian state, till then ambivalent and sometimes complicit with the mafia, was forced into fighting the mafia the way Falcone and Borsellino would have wanted it to. Sicilian society, until then broadly complicit with its cooperative omertà was forced to raise its voice. In classrooms of Sicily speaking about the mafia was no longer a taboo. Children and students were encouraged to speak up and push back, they were sent home to educate their parents.

Thirty years later the Italian state, Sicilian civil society, students and teachers, shopkeepers, lawyers, businessmen, aldermen, police officers, magistrates, and parish priests are celebrating Giovanni Falcone and the other victims of the mafia as heroes.

What does that mean, being a hero?

It isn’t just about their courage in life to do the right thing despite the danger they knew they were going through right to the point when it killed them. That is tragic as much as heroic.

Heroism is not merely the virtue of the hero but the example they give. People must allow for that example to change them. It is that change that turns prophets and victims into heroes, heralds of transformation, the finders of paths towards our improvement.

Five years after Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed it is disheartening to find that this country has been so stubborn in its categorical rejection of the Sicilian example. If the State here has taken any sides it was to side with omertà and with the impunity of the criminals Daphne exposed. Civil society has shown signs of life, but its impact has been momentary and the deal on ripping apart crime and public life has never been closed.

The mafia remains a taboo in our schools, in our churches, in our squares. The mafia still has us not talk about it, behave as if it doesn’t exist, let it do its thing while it uses our backs to hide behind.

Perhaps, in 25 years’ time, we’ll have caught up and some other crisis, some other sacrifice, some other killing shall one day wash the mud from our eyes.

But thirty years after Giovanni Falcone was killed, the events in Palermo tell us something else. Our job of keeping alive the memory of those who died fighting crime has no completion date. The search for truth and justice is forever.