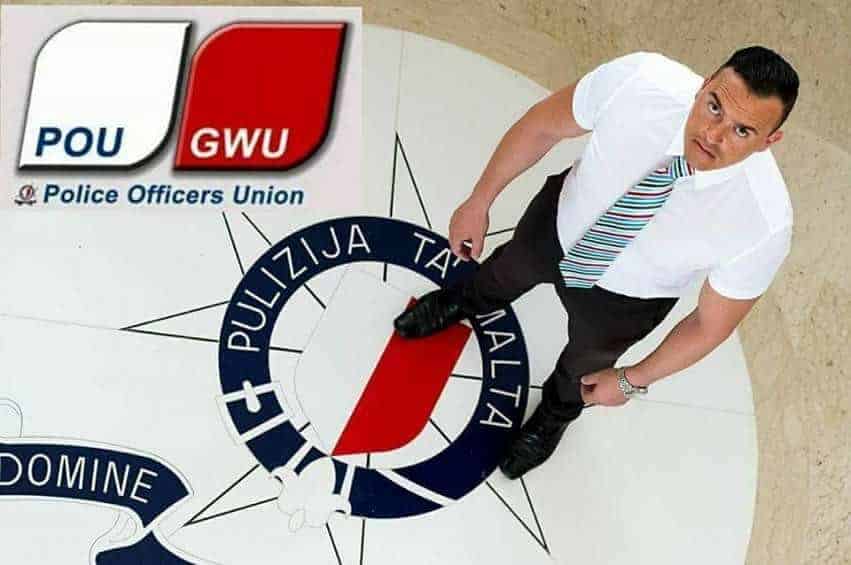

Sandro Camilleri is now head of the anti-money laundering unit of the police. The man is a bit of a caricature in and of himself and though I’m not above a little unkind mockery, I’ll pass on it this time. Perhaps I’m growing old. Older certainly than when I wrote this other piece – Inspector Big – around 4 years ago.

People are posting on their social media photos from Sandro Camilleri’s album. There are links to the time Daphne Caruana Galizia linked a video he posted speaking on behalf of a police officer who had been roughed up while off duty.

It’s not that he said anything wrong, or not much anyway. It’s just the way he says it. His posture, delivery, vocabulary, tone, and general demeanour. He’s an unintended parody of an SS-Standartenjunker, a miscast actor in ‘Allo! ‘Allo!

People are also posting pictures of Sandro Camilleri at Labour Party events, a tagħnalkoller through and through, waving the flag for Joseph Muscat, carrying on those thoroughly impressive biceps of his, the glory years of l-aqwa żmien.

People sharing these links and these pictures are not doing this because it’s funny. They’re doing this because almost as unamusing as Sandro Camilleri is, is the fact that Malta’s policing of money-laundering has been occasional, haphazard, barely competent, and clearly discriminatory, exempting just the politicians that Sandro Camilleri openly supported in the streets from any consequences for their crimes.

I find myself saying it every time I write about such appointments. I find myself wishing to be proven wrong, telling myself that I should not presume that someone who voted Labour in 2013 is incapable of doing their job today with conscience. I find myself taking a line of moderation, of trust in too oft betrayed human qualities, of hope that even someone who thought Joseph Muscat was just what the country needed might be moved by disgust at the corrupt regime he ran.

I find myself assuming that a successor of Ian Abdilla would not want their name besmirched in public as Abdilla’s was. That anyone following him would want to be remembered for being different, for not allowing evidence against ministers to gather dust in the drawers of their desk.

I find myself today hoping that Sandro Camilleri surprises us. That no party loyalty, no incipient fascist tendencies of self-reverential fascination with uniformed authority, that no muscular acid clouding his undoubted intellectual faculties, would stop him from enforcing the law without fear or favour.

But then my thoughts drift to what the people who laundered their money from corruption, trafficking, profiteering, and other crimes, protected by Joseph Muscat and his cronies, would be thinking today as they read that Sandro Camilleri is the policeman with the job of unravelling the complexities of their elaborate conspiracies and prove their baroque financial crimes in a court room. And I don’t imagine them quaking in their boots.

I can hear them chuckling as they click their heels and stab the air in a mocking salute, delighted that their friends in the government have found yet another way of letting them get away with it.