A few days ago, I titled a post about corruption within the police force as Serpico. I sort of left that word hanging there. I admit it was a bit of an indulgence. Someone in the comments board thought it was a corruption on the Maltese for snake or snakes.

Some background. Francesco Vincent Serpico is in his 80s now. When he was much younger in the 1960s, he was a detective in the New York Police Department. He was surrounded by petty police corruption in the force. It was mostly small-time racketeering. The police would take a cut from pimps and bookies and effectively protect criminals from other criminals and obviously from any law enforcement.

Sometimes it was worse than that. Officers would escort a drug smuggler from the airport’s apron straight to a police car outside the terminal bypassing customs and avoided inspection. They would then escort the ‘client’ safely to their destination. They called it the New York Taxi Service.

Serpico blew the whistle. He reported his colleagues to their bosses. But nothing happened. He did it again and again nothing happened. Giving up on the internal working of the Department, he gave the story to The New York Times who interviewed him for a front-page report that attracted national attention. The mayor was forced to set up an independent inquiry to investigate corruption in the NYPD.

One time he was on a drug bust with three of his colleagues. Since he was the only one to speak Spanish, they sent him to pretend to buy drugs. They were supposed to follow him. They didn’t. Vincent Serpico was shot in his face and the police did not make an ‘officer down’ call. Instead his life was saved by a bystander who called an ambulance.

The colleagues of Vincent Serpico tried to organise his killing. No one was charged.

When he recovered, Serpico testified in front of the inquiry set up by the mayor and then left the NYPD and the United States altogether living in Europe for 10 years.

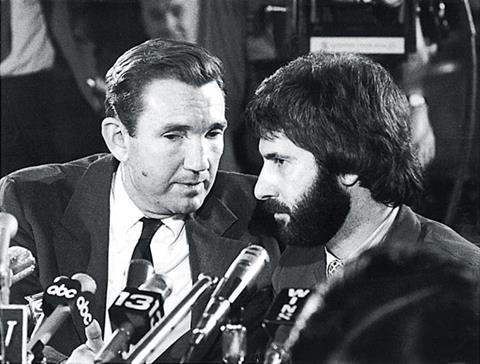

The story of Vincent Serpico is told in a Sidney Lumet film from 1973 with Al Pacino as Serpico.

I thought of that story because when the news emerged of corruption in our own police force my first thoughts went to the whistle-blower who took the lid off this. I thought of how the police bosses sat on his report for months. I thought of how senior officers that condoned or ignored the corruption and who are now in trouble themselves could find the identity of the whistle-blower and use that information to get out of dodge.

And predictably today the Times of Malta reports about threats sent to a police officer believed by many of the policemen arrested or suspected of corruption to be the whistle-blower in this case.

The fact is right now anyone who refused peer pressure to collect a share from the corruption would be under the suspicion of his colleagues. Right now, having been honest will be a very dangerous record. Even any of the police officers who refused to take bribes but also refused to report their colleagues will find it hard to look anyone in the eye, whether their colleagues who suspect them of snitching or the investigators who suspect them of corruption.

The responsibility to protect whistle-blowers is not understood here. Whistle-blowers – including a former policeman, Jonathan Ferris – are notoriously harassed, persecuted, driven to fear and isolation.

The only way to address that is not to rely on the police to police themselves. Right now, we cannot tell right from wrong. And more importantly they can’t either.

The institution of an independent inquiry is therefore imperative. The corruption of a bent cop is a criminal matter no doubt. But the corruption of a huge chunk of the police force is an institutional and cultural problem that cannot be addressed by those working for the institution and who are entirely seeped in the culture.

Repubblika yesterday reminded the prime minister of its urgent call for the institution of an independent inquiry. Only confronting the truth openly can have the desired effect of addressing institutional failure.

But there’s something else. The prime minister, his home minister and the chief of police must understand that the safety of the whistle-blower is their direct responsibility. On their conscience rests their life and safety. Whistle-blowers are not an inconvenience or an embarrassment. They are not snitches that have broken some code of silence that deserves any form of respect by the state for having been there forever.

Whistle-blowers are public servants whose job is hazardous and who deserve the protection of any state founded on the rule of law.

Ours isn’t.