A reader sent me this extract from the introduction of a book I had read several years ago. By sharing this quotation I do not endorse the author. His book is an apology and glosses over facts painting the black one white. And as the reader himself told me, the reference to the Nazis is useful only to a very limited extent. But there’s something this witness testifies from his own childhood that makes chilling reading today.

“Now I am publishing my memoirs. I have tried to describe the past as I experienced it. Many will think it distorted; many will find my perspective wrong. That may or may not be so: I have set forth what I experienced and the way I regard it today. In doing so I have tried not to falsify the past. My aim has been not to gloss over either what was fascinating or what was horrible about those years. Other participants will criticize me, but that is unavoidable. I have tried to be honest.

“One of the purposes of these memoirs is to reveal some of the premises which almost inevitably led to the disasters in which that period culminated. I have sought to show what came of one man’s holding unrestricted power in his hands and also to clarify the nature of this man. In court at Nuremberg I said that if Hitler had had any friends, I would have been his friend. I owe to him the enthusiasms and the glory of my youth as well as belated horror and guilt.

“In the description of Hitler as he showed himself to me and to others, a good many likeable traits will appear. He may seem to be a man capable and devoted in many respects. But the more I wrote, the more I felt that these were only superficial traits.

“For such impressions are countered by one unforgettable experience: the Nuremberg Trial. I shall never forget the account of a Jewish family going to their deaths: the husband with his wife and children on the way to die are before my eyes to this day.

(…)

“Our German teacher, an enthusiastic democrat, often read aloud to us from the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung. But for this teacher, I would have remained altogether nonpolitical in school. For we were being educated in terms of a conservative bourgeois view of the world. In spite of the Revolution which had brought in the Weimar Republic, it was still impressed upon us that the distribution of power in society and the traditional authorities were part of the God-given order of things. We remained largely untouched by the currents stirring everywhere during the early twenties.

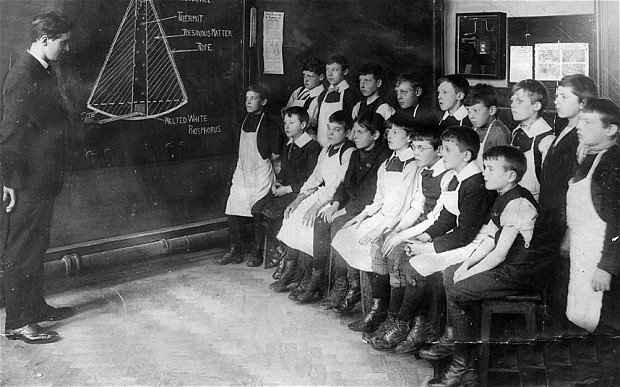

“In school, there could be no criticism of courses or subject matter, let alone of the ruling powers in the state. Unconditional faith in the authority of the school was required. It never even occurred to us to doubt the order of things, for as students we were subjected to the dictates of a virtually absolutist system. Moreover, there were no subjects such as sociology which might have sharpened our political judgments. Even in our senior year, German class assignments called solely for essays on literary subjects, which actually prevented us from giving any thought to the problems of society.

“Nor did all these restrictions in school impel us to take positions on political events during extracurricular activities or outside of school. One decisive point of difference from the present was our inability to travel abroad. Even if funds for foreign travel had been available, no organizations existed to help young people undertake such travel. It seems to me essential to point out these lacks, as a result of which a whole generation was without defences when exposed to the new techniques for influencing opinion.”

January 11, 1969. Albert Speer. Inside the Third Reich – Introduction