This long piece was completed in December 2020 and first published in Epoch No. 2 ‘Aftermath’, Spring 2021 (Epoch Press). Published again here with permission.

A journalist is blown to pieces in her car on a road not far from you. Everything is close to everything else on an island full of dust and noise and heat and the incessant drill-drill-drilling of construction.

A journalist is blown to pieces in the middle of a Monday afternoon, in the middle of October, while you are in the middle of teaching a very ordinary class.

A journalist is blown to pieces in a country you considered home where people you once thought you knew say she deserved it.

Everything that once had a particular shape, a familiar form, alters beyond recognition and you pick sharp fragments of glass out of photographs which will never look the same.

Everybody knew her name and suddenly, everybody knew she had been murdered. The brutality of it all. The speed of it all. The finality and the violence and the death.

And then the double horror, when people you thought of as friends don’t share your overwhelming sense of shock, when they don’t stare back at you with mouths stunned and open wide. It cannot be anything other than shocking – horrific – indescribably brutal – to blow someone up in their car as they’re driving away from their home in the middle of a quiet Monday afternoon. A journalist – a wife, a mother, a daughter, a sister – was blown up in her car, instantly, on a quiet road on a tiny island where everybody knows each other.

All roads are connected.

Somebody was watching from the top of the hill. Somebody was waiting on a boat just out at sea. A message was sent from one mobile to another and, at the sound of the explosion, the man on the boat smiled and sent a text to his wife telling her to open a bottle of wine.

‘No stone will be left unturned,’ said the Prime Minister, who fainted at an event two days before the bomb went off. No-one saw fit to inform the public about his unexpected turn for the worse. All lips were tightly sealed.

‘Daphne was killed by politicians,’ said the Minister for Justice before hastily changing his words. ‘Daphne was killed by criminals,’ he said.

On an island where cheap holidays drown out history, in a European country which originally waved the EU flag in proud celebration, a woman who single-handedly exposed every perverse abuse of power was blown to pieces in the middle of a Monday afternoon.

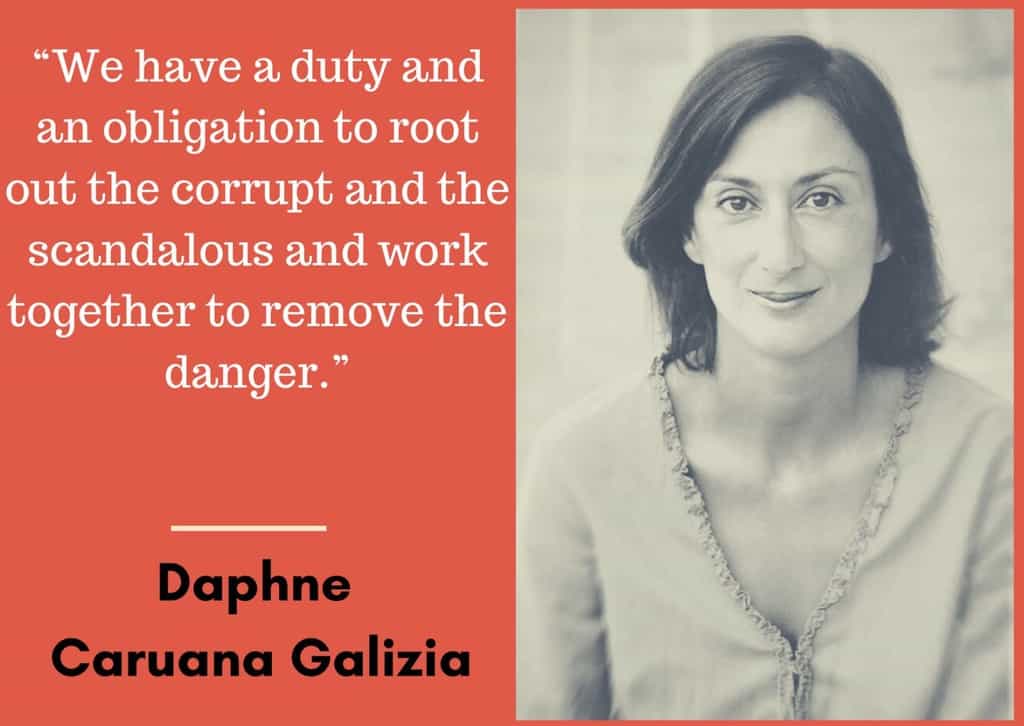

Daphne was her name. Everybody knew her name. Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Then that bleak awfulness when many who knew her name were not appalled.

‘It’s Malta,’ said someone.

‘What do you expect?’ asked someone else.

‘She hurt people,’ said another.

On the night of her assassination, a policeman publicly celebrated her death on Facebook, referring to Daphne as cow dung. He was suspended on half-pay. Three years later, he’s still on the police payroll despite failing to turn up for disciplinary hearings.

Shortly after Daphne’s murder, thousands of people filled the streets of Valletta in protest. Banners declaring Malta as a mafia state were hung from public buildings. Daphne’s final words, written just before she got into her car that Monday afternoon, were emblazoned on t-shirts, posters, placards.

‘There are crooks everywhere you look now. The situation is desperate.’

The situation got more desperate as the numbers of those gathering to protest dwindled. In a country cloaked in omertà, people huddled in their homes, protecting their jobs, their families and, far too often, their ill-gotten perks and gains. In an educational institution teaching English to the world, I was told to lower my voice because that colleague who shared a locker next to mine votes Labour.

Coming from Scotland, I naively assumed that the assassination of a journalist transcended petty political allegiances. Focusing on Trump, Brexit and Scottish independence, I’d dismissed Maltese politics as parochial, like a friendly football game. I hadn’t been paying attention.

Soon after Daphne’s murder, a group of women came together. Mothers, wives and daughters just like Daphne. We set up camp in front of the Office of the Prime Minister. A group of us went to meet him in November, demanding the resignation of the Attorney General and the Police Commissioner. None of us smiled when we shook the Prime Minister’s hand, which felt cold, clammy, perfunctory.

Once the media had left and the cameras stopped clicking, the Prime Minister visibly relaxed, sitting in front of six women whose fixed gazes could have turned him into stone. He smiled, poured himself a glass of water, settled down for a cosy little chat. We stood up and left.

That same month, a delegation from the European Parliament announced they were coming to Malta to investigate the rule of law.

‘When the MEPs visit Malta, they will do so with a sense of serenity,’ said the Prime Minister from the rock-solid fortress of his castle in Castille. Serenity, in a land where a journalist had been blown to pieces in her car.

I was teaching when the news came through that ten men had been arrested in connection with Daphne’s murder. It was the 4th of December. My birthday. My friend in London messaged me to wish me well. She asked if I’d heard about the arrests. I replied it was a stitch-up, bluff. In a normal country, the Police Commissioner would have delivered the news. In Malta, it was the Prime Minister himself, Joseph Muscat, a frequent target of Daphne’s incisive blog. Live on television, he boasted that ten men had been caught and gave his ‘personal commitment’ that those responsible for the killing would be found.

Ten men turned into three and three years later, they are still on trial. No convictions have been made. Two of those originally arrested but quickly released are brothers, bomb makers, with international links to the Italian mafia, Libyan fuel smuggling, drug smuggling and other delectable activities. One of them was the business partner of someone whose cousin was the right-hand man of the then Prime Minister, his Chief of Staff, whose name is Keith Schembri. Schembri has been accused of ordering Daphne’s murder.

‘Mexxi, mexxi, mexxi,’ he said, giving the go-ahead to continue with the assassination plot.

All roads are connected.

The bomb-making brothers roam freely around Europe. Schembri was arrested in November 2019 and then released without reason. When he was arrested, he claimed he’d lost his phone. Phones were used to blow up a journalist and Schembri shared a private WhatsApp chat with the then Prime Minister and the man now charged with masterminding the assassination, Schembri’s childhood buddy, Yorgen Fenech. The age gap would have been more significant when they were younger, but they still claim they were friends as kids. Everybody knows everybody in Malta.

Those demanding justice for Daphne’s killing were accused of being traitors. Ghoulish memes and grotesque caricatures depicted their deaths. One of these showed my friend and fellow activist standing at the graveside of her partner, an outspoken critic of the Maltese government. It chilled me to the bone.

Daphne’s family were not allowed to grieve. Her oldest son heard the explosion minutes after he said goodbye to his Mum. He knew exactly what it was, no matter how much he hoped he was wrong. He ran, barefoot, from their home, saw smoke and fire billowing from the field.

‘This is what war looks like,’ he said. ‘When there is blood and fire all around you, that’s war.’

The same evening, the day he found his mother dead, he was forced to sit in a cold hard courtroom for hours to ensure that the magistrate, a woman who loved to party with the Party, was removed from the case. Matthew and his shell-shocked family were made to wait.

The trolls crawled out of their dark dank caves, tempted by the tantalising flash of silver. They relished the idea that Matthew had been responsible for killing his own mother and screamed gleefully about a laptop that, they screeched, showed Daphne’s family up as liars, scumbags, thieves. The dead and sunken eyes of creatures who hadn’t managed to evolve from the noxious mud were suddenly alive, dragging their heavy chains upwards in some pitiful semblance of applause.

In an effort to assume some human guise, the trolls sat on the park benches opposite the Law Courts. They took the form of old men, gnarled and rigid, bent and twisted by year after year of stories persuading them that they deserved more, they were entitled to the best things in life, they had been deprived of what belonged to them, but their day of glory would sure as hell arrive.

The Witch of Bidnija hated them. The Witch of Bidnija insulted them. The Witch of Bidnija mocked them, jeered at them, looked down on them, attacked them, wanted children with cancer to die, wanted to undermine all that was good about Malta, laughed and cackled at their girlfriends and their wives. The Witch of Bidnija wanted to destroy them so we will destroy her.

Someone set fire to Daphne’s house. Someone cut the throat of her pet dog. The Mayor of a town gathered a mob together and chased Daphne down the street until she took cover inside a convent. The Mayor liked to boogie with the magistrate who was on duty when Daphne was assassinated. Seven months after the murder, this magistrate was made a judge.

She sits in the Law Courts where the old men toss out curses at the women who place flowers and candles and photos at the protest-memorial, a monument to Faith, Fortitude and Civilisation. The Justice Minister ordered the protest to be removed night after night. This year, he was found guilty of violating human rights and was rewarded by becoming the Minister for Education.

Three years on, the protest-memorial remains intact, a sign to all the world that true justice will happen, no matter how long it takes.

Less than a year after Daphne’s murder, the Justice Minister put barricades around the memorial, sneakily believing that the protest would be quelled.

‘Daphne was killed by politicians,’ he once said.

Minutes before a civil liberties delegation was arriving from the European Parliament, the Justice Minister busily set about erecting boards. He brought in his builders who bang-bang-banged in nails to crucify dissent.

The barricades went up on Victory Day as state dignitaries gathered to commemorate Malta’s triumph over the Turks all those centuries ago. Wreaths were laid in solemn reverence to Malta’s glorious past when in came the builders with their hammers and their screws. So eager was the Justice Minister to put the barricades in place that he didn’t even have time to remove the wreaths before the workmen rushed in. Visible behind the boards, they wilted and faded as the days and weeks passed by.

‘No stone will be left unturned,’ said the Prime Minister as his Justice Minister banged up barricades.

A journalist had been assassinated so we placed flowers and candles in front of the boards which also provided a ready-made canvas. Night-time artists added colour and meaning to a wall constructed twenty-nine years after the people of Berlin rose up to pull theirs down.

‘The truth is out’

‘Daphne was right’

‘We demand Justice’.

One night, right at the beginning of it all, a group of us guarded the protest-memorial to prevent our democratic right to protest from being dismantled. We went to Valletta in the morning and set up a banner in front of the boards. We handed out leaflets to passers-by informing them of their constitutional rights to freedom of expression. Some Saturday shoppers, angered at the thought of liberty, tore up the leaflets and threw them on the ground.

As soon as we left, our banner, our flowers, our candles, our photos – every single thing we’d placed there peacefully – disappeared. Responding as any citizen would when they realise they’ve been robbed, we went along to report the crime to the police. Valletta happens to be the punishment ground for bobbies out of favour with the powers that be and we were reliably informed that the orders to steal our property had come directly from the Justice Minister under the auspices of the eerily Orwellian Cleansing Services Department. Reclaiming items that legally belonged to us, we wheeled our possessions back to the protest site in shopping trolleys, patiently restoring our resistance once again.

It was the night before the eleven-month anniversary of Daphne’s assassination. We stayed up all night safeguarding our constitutional freedom to express our outrage. In a European country, we kept our eyes wide open to any stealthy attempts to rob us off our freedom.

Malta is a tiny island. Everything is squeezed into the same space at the same time. That evening, a Gay Pride celebration paraded triumphantly down Republic Street, the main street of Valletta where everything takes place. A party was in full swing. Hungry for votes, the government – which indulged in opening offshore accounts, siphoning off the country’s wealth, preaching propaganda through its government-controlled TV, bleeding the country dry of healthcare and education – knew capturing the pink vote was mandatory. Gay Pride in Malta seemed somewhat mercenary.

As the floats jived past, one reveller – a well-known personality in the entertainment industry – found time to pause atop his disco bus. He turned to the protest-memorial and taunted the assassinated journalist, jeering at a dead woman who’d always argued in his defence. In amongst the partygoers was the Justice Minister sporting rainbows on his face. The topsy-turvy of the grotesque carnivalesque.

Close to midnight, with our candles lighting up the darkness, another group of celebrants came by. This was a ceremony for a saint and a brass band played music which didn’t always hit the right note. They erected a tall column and a young man was given the privilege of positioning the holy icon right at the top. The crowd gasped and cheered and clapped. Minutes later, the saint was toppled and the merrymakers packed up their bits and bobs and scuttled off as quickly as they’d come.

The Law Courts stared at us, silently and solemnly, as we maintained our guard. Sitting on stone steps surrounded by the objects of our protest, we stared straight back and we refused to move.

By the time the barricades were painted with flowers and statements, we knew – everybody in Malta knew – who owned 17 Black. Who owns 17 Black, we’d asked since the moment Daphne was assassinated. Who owns 17 Black?

In November 2018, journalists who refused to stop investigating Daphne’s stories informed us that Yorgen Fenech, a familiar name in the shady world of Maltese business, owns 17 Black.

When the news broke, I phoned my friend and fellow activist.

‘We should be out there in the streets,’ I said.

We went to Valletta, to our boarded-up memorial, and we met Daphne’s youngest sister, who was calmly and quietly attaching photos and statements of protest to the plastic covering designed to keep us out.

We knew who owned 17 Black yet the capital city was shrouded in silence.

17 Black was a Dubai-based offshore company exposed by Daphne in the months before her killing. 17 Black was an offshore company designed to pump five thousand euro daily into the accounts of the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff – the guy who lost his phone – and the Minister for Tourism, Konrad Mizzi, who’d started out as Minister for Energy before being outed by Daphne via the Panama Papers three years after his Party won the election. Likewise with Keith Schembri, but no resignations were deemed necessary when a slap on the wrist and a shift of portfolio can do the job nicely or, in the case of Schembri, you stay exactly where you are.

Mexxi, mexxi, mexxi.

Go on. Go on. Go on.

All roads are connected.

Yorgen Fenech, now charged with complicity in the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia, was the owner of 17 Black. Yorgen Fenech, director of the government’s flagship power station, Electrogas, owned 17 Black. Yorgen Fenech, who, as it later transpired, talked of how he’d push Daphne from the twenty-first floor of his money-saturated tower to dash her brains out on the rocks below.

Daphne was a mother, a sister, a wife, a daughter, a living breathing human being who, only months before she was assassinated, wrote:

Malta is in a dangerous place, and now we can no longer say that it is corrupt politicians who have brought it to this point, for it can no longer be denied that those corrupt politicians are a reflection of society.

There is something else I should say before I go: when people taunt you or criticise you for being “negative” or for failing to go with their flow, for not adopting an attitude of benign tolerance to their excesses, bear in mind always that they, and not you, are the ones who are in the wrong.

Daphne was right and these three words became a chant, a slogan, a hashtag, a repeated refrain. Daphne was right.

When she was alive, she was right. After her murder, revelation after revelation continued to prove her right. Working alone on a tiny island riddled with corruption, Daphne’s assassination meant everybody across the world knew she was right.

Everybody across the world now knows her name. Her name is Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Every month, a small group of citizens gathered at the protest-memorial for a vigil. Every month without fail. People spoke, sometimes I spoke, calling the Justice Minister to account by name. Malta being Malta, I bumped into him once in the street, only days after he’d placed wooden boards around our protest site. With no respect for personal space, he stood uncomfortably close before leering into my face and spitting out the words ‘You believed everything Daphne Caruana Galizia wrote, didn’t you?’

This was the Minister for Justice whose government had sworn to leave no stone unturned.

This was the Justice Minister who looked into the camera and said, quite clearly, ‘Daphne was killed by politicians.’

This was the Minister for Justice, hissing contempt into my eyes.

Daphne knew she was in trouble long before they killed her. She’d been demonised and dehumanised, threatened and attacked, throughout her life. Ten days before her murder, she spoke of how she’d been made into a national scapegoat for almost thirty years and how dangerous this situation had become now the Labour Party were in power.

When she was murdered, she had forty-seven libel cases mounted against her, many of these filed by politicians, including the Prime Minister.

When she was murdered, in a European country, the Minister for the Economy had frozen Daphne’s bank accounts. She couldn’t even get access to her own money in the months before her death and she was on her way to the bank because of this when the bomb was detonated.

The Economy Minister, Chris Cardona, had taken umbrage at Daphne’s accusation that he’d got down and dirty in a German brothel, that he preferred a threesome with a prostitute and his private aide to engaging in boring nonsense like EU business. And he really did get his knickers in a twist. He was so incensed that he pursued the lawsuit with Daphne’s family after her brutal murder, then let the case drop before mobile phone records could be produced which would, if true, reveal his innocence.

Each and every road is connected.

In some Svengalian game of Cluedo, Chris Cardona was put into the frame shortly after the arrest of Yorgen Fenech. Mysteriously taken ill while in prison, Fenech’s doctor delivered a note to his hospital bed from someone who just so happens to be another of his patients: Keith Schembri. The note, typed up and added to with handwritten comments, was an attempt to pin the blame for Daphne’s murder on Cardona who, after all, had been seen drinking with the two brothers accused of planting and activating the bomb. He also let his hair down at a bachelor party with one of the assassins, only four months before Daphne was murdered. At this point, the plot to kill her was well underway.

Given that every self-respecting Economy Minister also works as a lawyer, Cardona has a legal history which intersects with the criminal lives of those who, while gainfully unemployed, fluttered away millions of euro in Yorgen Fenech’s upmarket casino.

The scheming and the planning and the plotting are as vulgar as the conspirators themselves. Tacky. Sordid. Vile. But we’re accused of being elitist when we point this one out. We’re accused of being elitist for aspiring to better things.

Daphne aspired to better things. Six weeks before she was assassinated, she wrote:

I promise to continue providing you with the oasis of sanity you want and need, as long as I am able to do so. And remember always that more and more people who are in the wrong do not become right by sheer force of numbers.

Earlier that year, only months before her death, the Labour Party called a snap election. Daphne knew there was something big behind all this but she couldn’t put her finger on exactly what it was:

Whatever the reason is, it’s bound to be the basis of a massive news story, and that is what we have got to focus on. My antennae tell me that whatever it is, it’s so bad that we’ve got to discover it before the general election – and not afterwards, which is what Muscat wants.

She also told one of my friends, a fellow journalist, she felt her time was running out.

I never knew Daphne. I only got to know her when she’d died. In the aftermath of her assassination, she touched so many lives. One of them, and indisputably, is mine.

When something is wrong beyond wrong, you must do whatever you can to put it right.

When something is wrong beyond wrong, you cannot close your eyes and hope that everything will be okay if you cross your fingers and wish it hard enough.

When something is wrong beyond wrong, you have to focus all of your attention on the fight.

The 16th of October 2017, and the words ‘They’ve got Daphne’ are etched forever on my mind.

My friend gave a speech at one of the vigils:

My only master is my conscience and on the 16th October 2017, I knew that life in this country would never be the same again. There was a time before and now would come the ‘after’.

The after, which began more than three years ago, is a constant living through of new shocks, new breakthroughs, new horrors and yet new joys. On the day marking 37 months since their mum’s assassination, Daphne’s three sons were awarded the Magnitsky Human Rights Award for their Outstanding Justice Campaign. It doesn’t bring their mother back, but it brings the possibility of justice one step closer.

There was a before and there is an after, and the after must bring justice.

After 12 years of living in Malta, I moved back to Glasgow. Malta had become a building site where permits to construct unsafe and unsavoury buildings were doshed out like sweeties. No questions asked when you know the right people. No questions asked as millions of euro are slipped between hands. My head felt crushed by diggers and drills.

One Saturday, less than a year after Daphne’s murder, I woke up to discover workmen hanging from ropes and planks right opposite my house. They weren’t wearing helmets. Precautions are an unnecessary expense when you’re dangling from a great height on a wooden plank that would scarcely bear the weight of a couple of pot plants. It was the first Saturday in a long time that was free of protests and here were three men, whose lives were put at risk, dangling right outside my window.

I didn’t know what to do.

I found the number for the Health and Safety people in a country where health and safety had never existed. When I first moved to Malta, I found the lack of attention to anything approximating rules somewhat quaint while being extremely nervous whenever I came across a crane precariously balanced with bricks. I’d rather chance my life and walk on the death-defying roads than be pinned to the ground by metal girders. There are one thousand and sixty-two different ways to die in Malta, all of them unusual.

I phoned the number for the Health and Safety people and, unable to get through, I left a message. I emailed them. I didn’t know what to do.

I took photographs of the three men, all migrants, being forced to work in conditions that put them in peril of death. We began talking and hearing something was afoot, the foreman arrived on the roof, all smiles, sweetness and light. Maltese, with a moustache, the man was small and fat.

‘They’re used to it, you see,’ he said, talking as if the three men, perched on a wooden plank high above the air, were simply not there or certainly not worth acknowledging.

‘It’s very hot,’ he said, as an excuse for why his workers were not attached to harnesses or anything which might cushion them if the ropes gave way.

When I explained that what he was doing was illegal, that he wouldn’t let his sons or brothers work in these conditions, that he was placing the lives of his employees in obvious jeopardy, the foreman disappeared and came back with an assortment of flimsy equipment which he then used in a theatrical display of benevolence. He seemed convinced that providing the bare necessities in exchange for less than the minimum wage transformed him into Father Christmas and all beneath the heat of the scorching Maltese sun.

When I turned my camera towards him, his jolly persona dropped.

‘I’ll get my lawyers on to you,’ he threatened. ‘I know where you live. Get back inside! Get back inside! Get back inside!’

Someone suggested I go to the police. In the land of Kafka, your choices are limited.

The police station was quiet when I went in. A placid portrait of serenity. Three policemen idling away their time in a country where crime is oozing out of every piece of rock and waving its proceeds in your face. Three policemen, with nothing to do, in a country where a journalist was assassinated with impunity.

‘You have to file a report. You have to open a court case. You need a lawyer.’

‘I don’t want to file a report. I want to file a complaint.’

‘You can’t.’

‘Is there anywhere in this country where I can file a complaint?’

‘No. And anyway he didn’t really threaten you. He didn’t tell you to get back inside or he’d kill you.’

I hadn’t expected much better. I’d known for a very long time that in Malta, there was no-one to protect us. Only months later, a young Libyan construction worker fell seven storeys to his death, neither the first nor last of many. Friends of my friend saw him struggling to keep hold of the rope before he hurtled downwards. Everyone knows everyone in Malta.

Not long after I returned to Glasgow, a woman was buried beneath the rubble of her own home in the middle of a Monday afternoon. It’s always in the middle of a Monday afternoon. Her house was right beside a construction site. When corruption strikes, it’s lethal, and there is no-one to protect you.

All roads are connected.

The day after she was killed, in that safest haven called your home, a photo was published in the newspaper showing the language school where I used to work. I gasped. A woman had just been obliterated when her house collapsed and my old school was teetering on the precipice of disaster.

My flat was already on the market when my boss announced that contractors were going to start digging a seven-storey underground car park right beside our school. I sold my flat that same weekend.

One year on and back in Glasgow, I looked at the photograph. I thought of the woman buried alive in her own home. I spoke to friends and former colleagues who told me the building where they worked, where I had worked, had shaken so badly while they were teaching that they were terrified.

Nowhere is safe in Malta. All roads are connected and corruption kills.

They kill journalists in Malta and no matter how much the guilt is exposed, no matter how many people are incriminated with enough evidence to bang them up for life, the criminals saunter down the street scot-free. They show no shame when they walk past Daphne’s family. They show no sense of shame.

Maybe it’s this that I can’t stomach but there’s so much that I can’t stomach. The feeling of nausea is so overwhelming and so constant that it becomes normal. In Malta, nothing is normal. Malta is not a normal country.

It isn’t normal to sit in a café with a friend and journalist who sends you a text to tell you that the man sitting at the next table is a former cop turned lawyer who acted for one of the brothers accused of blowing up the journalist. A former cop turned lawyer who worked in the Economy Minister’s legal firm and was accused of complicity in a hold-up at the HSBC but acquitted on the grounds of insufficient evidence, nine months, in fact, before Daphne was assassinated. Lawyers in Malta are never quite what they seem.

Nothing in Malta is quite what it seems and yet the guilt of the government is transparent.

‘Daphne was killed by politicians.’

When I first moved back to Glasgow, at the end of October 2019, I couldn’t settle. I couldn’t adjust to walking down the street without looking behind my back. I couldn’t accept that you could talk about politics and loudly in bars. I couldn’t shrug off the heightened nervousness and fear. I couldn’t sit down at a table and do small talk.

‘You’re not really here,’ said someone.

‘Why don’t you get involved in UK politics?’ asked another.

‘There’s corruption everywhere,’ said someone else, ‘and Daphne isn’t the only journalist who’s been murdered.’

When you live in a safe country, it’s hard to imagine that there’s a small island somewhere in Europe, somewhere in the Mediterranean, where people throw a framed photograph of a dead journalist at the journalist’s youngest sister so it hits her and it hurts her in ways that are beyond the imagination.

Safely back in Glasgow, the news came through that Yorgen Fenech had been arrested, trying to sail away from the island on his luxury yacht. Then came the news that Keith Schembri had been arrested. I watched live footage of my friends, protesting in huge crowds outside parliament. There was a picture of one of Daphne’s sisters pressing a photo of Daphne against the windscreen of the Justice Minister’s car. She told him that this was the face he should see when he goes to sleep at night. This is the last face he should see.

I got a flight back to Malta that same week.

We protested and protested and protested, in a land where the idea of protest had been anathema. We protested and protested and protested, every night and every single day. Thousands of people in the streets of Valletta who, despite the anger, never resorted to violence. Thousands of people, amongst them Daphne’s family, demanding an end to corruption and that the dirty mafia crooks be brought to trial.

One night, we surrounded parliament and blocked all the entrances. Like cornered vermin, villains wearing Gucci crawled beneath the sewers to escape, sticking to the stench of muck and slime.

One particular night was spine-chilling. It was a Thursday and no protests had been called. The villains wearing Gucci took that as their chance to hold a night-time cabinet meeting. Journalists gathered outside the office of the Prime Minister when a police statement was delivered. Keith Schembri had been released and no reason was given. Schembri, accused of ordering Daphne’s killing, had been released from police custody without any explanation as to why.

If you want to understand how the Mafia works then come to Malta, where stitched-up and sewn-up are power for the cause. And the cause is money, millions and billions of sleazy blood-stained euro stuffed into every nook and cranny of this infested isle.

That night, in the early hours of the morning, Malta declared itself a Mafia State in front of the eyes of the whole world.

‘We killed a journalist,’ they were laughing. ‘You think we’re going to stop now?’

Shameless, brazen, drunk on impunity, the bastards simply did not give a fuck.

We watched everything live on Facebook. We watched, horrified, as journalists, including Daphne’s youngest son, were locked inside the office of the Prime Minister by mindless thugs. We watched in disbelief as Daphne’s youngest son asked who the hell they thought they were, these menacing minders. Who the fuck did they think they were, these men who had declared themselves the gatekeepers of hell?

My friend filmed it all, the journalist who’d let me know that a bent copper turned lawyer was a hair’s breadth away. My friend, locked up with all the other journalists in Castille, kept her phone steady and caught every moment of their brutish captivity on film.

One year later, three men charged with holding journalists inside a building against their will were found not guilty. If you want to understand how the Mafia works, I give you Malta.

Our protests continued. We never stopped protesting. From the small group of people who were mocked and taunted for daring to hold a monthly vigil and ensuring that the flame of truth and justice was kept very much alive, we swelled in numbers and conviction. From a stream, we grew into a river and from that river we became the sea. We were now an ocean of opposition with a force fuelled by persistence and anger and the knowledge we were right. Daphne was right. The criminals that killed her knew she was right. They murdered her in cold blood and defiled her in death because Daphne was right and she will always be.

Justice will have a strange taste when it arrives. It won’t turn the clocks back or bring any sense of serenity. But, and to use Daphne’s own words, ‘where I can do anything to avoid unfairness or to set it straight, then I will.’