The polling gap between the PL and the PN is a yawning chasm. Although the margin yawned wider in the chaotic interregnum of Adrian the Inadequate, the PN never in all the time since the 2017 election, polled better than the PN.

Incidentally the PN has almost never polled better than the PL since sometime in 2005. Labour’s support has been consistently more cohesive, their funding (mysteriously sourced and irregularly acquired) steadier, their propaganda tools more oblivious to truth and therefore more effective in keeping its crowd bound by hostility to an outside reality that did not confirm with the way the universe was explained to them by One TV.

Why campaign then? The 2017 election result justifies that question. My first ever article on this blog was an analysis of what had gone wrong in that PN campaign, and it certainly wasn’t the messaging, the packaging, the content, the discourse, or the presentation. Nor certainly was it about being right or wrong about the main issues of that campaign. Labour had already been exposed for wrongdoing by the Panama Papers. The PN was right that Labour’s re-election after those revelations would harm the country. If being right were enough, Labour would have been trounced for letting the country down so badly.

Campaigning is still important for several reasons.

Electoral defeat is not an absolute value. Surrender without a fight sets the scene for the years that would follow. A one-side election like that would concentrate power in government without qualification, unopposed, without resistance or an alternative. Surrender without a fight is not survival to fight another day. It is permanent resignation.

The reach of a ruling party through the abuse of its incumbency is effective and perhaps in many respects unbeatable. But expectations of greedy voters grow and a government’s ability to meet them shrinks, not out of any moral qualms that might set in but simply because asking the question “do you need anything?” too many times brings about answers that are simply beyond the reach of even the most corrupt politician. Disappointment in one’s source of favours, and trying one’s luck with the other side is, disgracefully, a reason why some people might start listening to the political arguments or even just shift their chips on the table.

It’s the economy stupid, they say. And the state of the economy is nowhere near as rosy as it was in 2017. Some of that is caused by covid and for some people that will be a mitigating consideration that will keep them tied to the PL for a few more years. Some people won’t care about the cause but will punish the government for whatever hardship they suffer. Consider how the international oil price hike never appeased voters in 2013 who voted Labour for cheaper electricity bills.

Being right – about corruption, about moral conduct, about standards in public life – is not alone enough to win elections as we know. But it helps. And only campaigning can persuade anyone about being right. Not everyone who voted Labour in 2017 is entirely pleased with Labour’s record in governance. The implications of the Robert Abela scandal have not set in yet and it is hard to see them have an actual impact on people’s voting decisions at this election (though they will determine Robert Abela’s fate over the next two years). But Labour voters are not impressed by Konrad Mizzi’s non-answers at the PAC, and some are wondering whether this might not be the time to get their party to wait out the next term to properly clean up its act.

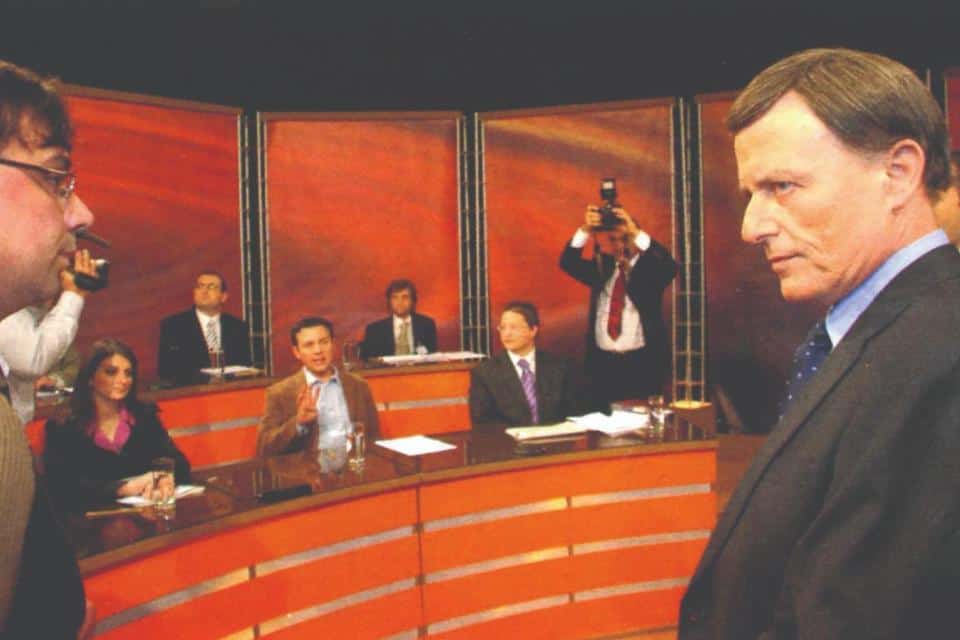

However consistent polling is throughout a Parliament’s term, there is no time when shifts are anywhere as dramatic as during an electoral campaign. There’s the classic case of the 2008 election campaign when the Mistra scandal concerning Jeffrey Pullicino Orlando pulled the ground from under the PN’s feet. The PN’s support dwindled vertiginously, shifting thousands of votes from its cushion of advantage over Labour at the start of the campaign to the point that on election date the outcome was entirely uncertain. Only 1,800 votes separated the two parties on the day of the election and if the ballot was held but a few days later it is likely Labour would have won.

Keep it real. Labour’s current polling advantage over the PN is several orders of magnitude greater than the reverse gap in 2008. It is likely that 33 days of campaigning could never be long enough to bridge this sort of gap. But go back to point number 1 on this post. The extent of the defeat is relevant, and campaigning can have the effect of reducing the severity.