Netflix released this week a documentary version of the Black Mirror episode from our past. ‘The Great Hack’ is a documentary that tells the story of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and how this was unpacked with the help of whistleblowers by The Guardian and Parliamentary Committees in the UK and the US.

You have been using Facebook thinking that your tastes, your likes and dislikes were as private as a chat with your family over a week-day dinner. But that data has been used to manipulate elections — in the past — and knowing this tells us that it is quite possible we may never have another free and fair election again.

It’s an excellent documentary, by the way, so make the time. And remember in the meantime that Alexander Nix, disgraced CEO of Cambridge Analytica, was scouting for clients in Malta in 2012 and was turned down by the PN at the time. Emails show he talked up the up and coming Joseph Muscat at the time. You can work out the rest.

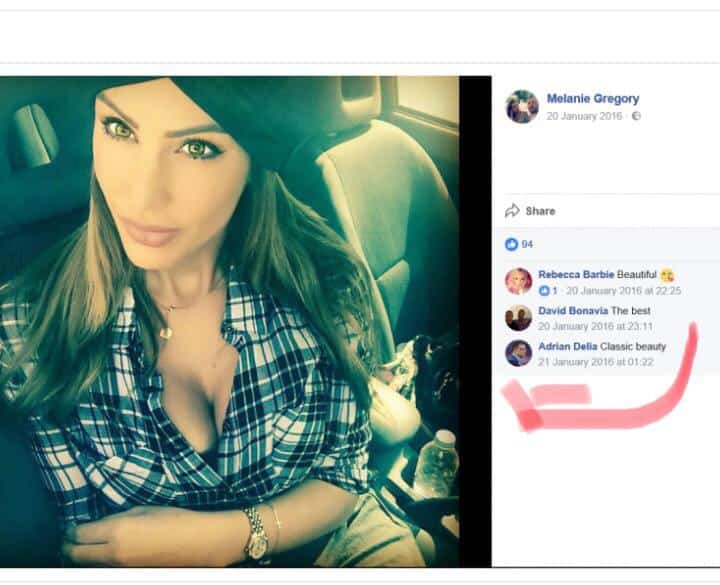

You don’t have to behave stupidly on Facebook. Some are better at that than others.

You just need to be there long enough for your quirks and your fears to be automatically figured out and those vulnerabilities consciously exploited by propagandists.

And they can get you to vote anyone and anything. They can get Turkeys to vote for Christmas. They can get you to think these are ‘the best of times’.

But there’s a time from before Facebook, a phase were we have been intellectually prepared to carve out for ourselves echo chambers of comfort and to block any challenge to that sphere with walls of fear and prejudice.

This study, published on the American Economic Review and co-authored by Ruben Durante, Paolo Pinotti and Andrea Tesei, finds a stark correlation in voting behaviour in Italy between people who have had Canale 5, Italia 1 and Rete 4 in their homes for longer and voting for populist parties — not just Forza Italia, the party of the owner of the three stations, but even Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S), the party that is ideologically opposed to Forza Italia but just as populist and superficial.

Maltese voters do not vote for Forza Italia or M5S. But they’ve been watching Mediaset channels a long time. There’s a generation that watched TV between 1985 and 1995 that subsisted on a diet of day-time TV made of dubbed Japanese cartoons, pneumatic and almost naked showgirls, quiz shows (often with pneumatic and almost naked showgirls) and movies that were careful to avoid exciting brain cells too hard.

For a long time these channels did not carry even a news service, let alone documentaries, debates, analysis and culture. It was an era of broadcasting intended for the vigour of arousal not the rigour of intellect. Ciao Darwin indeed.

Qualunquismo — the politics of indifference and ambivalence — and menefreghismo — the politics of could not care less — have permeated Maltese thinking perhaps partly through Bim Bum Bam, La Ruota della Fortuna and reruns of Commando dubbed in Italian. Sure, we participate almost universally in the act of voting. But do you see much thinking going on?

This study focuses on Italy perhaps because of the neat relationship between Silvio Berlusconi’s TV business and Silvio Berlusconi’s political party. But although Italy’s dumbing down of TV is both familiar and spectacularly self-evident, this phenomenon is by no means exclusive to Italy (and Malta).

What more fertile ground can there be than a brain that is desensitised to critical thinking and habituated over so long to superficial quick-fix stimuli, for the shallow pinches of personalised light-weight emotionally charged Facebook ads?