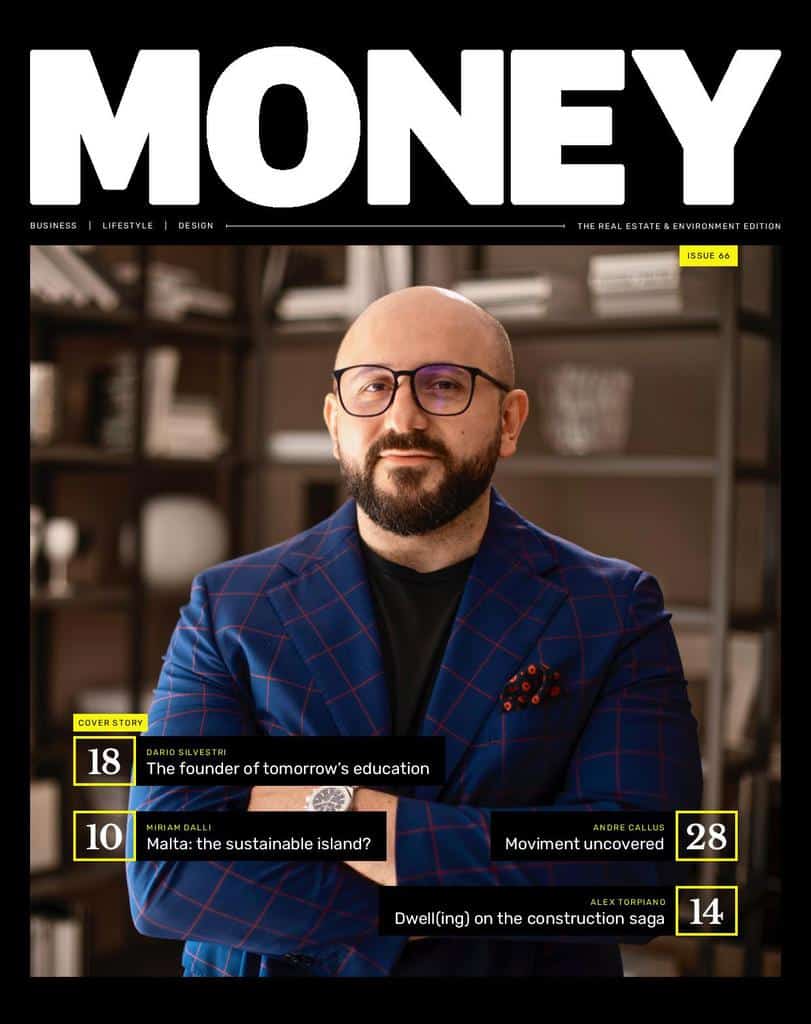

This is my article in this month’s Money Magazine:

In March 2019, four months after the world learnt that Yorgen Fenech owned the company that Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi’s accountants told Mossack Fonseca was their “target” to pay them, with others, $2 million for no reason whatsoever, the chief executive at the Planning Authority, Johann Buttigieg, was exchanging text messages with the same Yorgen Fenech.

We learnt that Yorgen Fenech told Johann Buttigieg that another tycoon owed him money. ‘What project of his should I take over?’ But, of course, there would be a reward for that advice. ‘I’ll split the project with you.’ ‘This one belongs to you,’ Buttigieg told Fenech. What an upright man. ‘I’ll go into business with you anywhere (else),’ he went on as they discussed workarounds for Yorgen Fenech’s other major planning applications.

When the text messages emerged in the public consciousness, Johann Buttigieg had already left the Planning Authority.

Others were also exposed for the damage they were doing while still running things at the Planning Authority.

Consider Matthew Pace, since charged with his most famous client Keith Schembri for helping him stash money neither one could explain. In 2013, he was appointed on the Planning Authority board. He proceeded to set up a real estate agency and acquired the Re-Max franchise. And he used his agency to advertise and sell apartments in St George’s Bay that existed as yet only in the imagination of one Silvio Debono.

The DB tower in Pembroke was still due to be discussed (let alone approved) by the Planning Authority board. But, when it came to it, Matthew Pace voted to have it approved. Conflict of interest? He didn’t think so.

Campaigners sued, and the Planning Authority’s first attempt to allow the DB monstrosity to be built was struck down. As a result, Matthew Pace was forced to resign.

Alfred Pule replaced him. Pule had not sat on the Planning Authority board for more than a few weeks when he voted to approve an application by Joseph Portelli, the Gozo-based tycoon. The latter owed Yorgen Fenech money to turn a long-abandoned room overlooking the cliffs of Qala into a sprawling villa. It later emerged Pule and Portelli were in business together, erecting a “blokka fletsijiet” that ruined the aesthetic harmony of a classic street in Ħal Lija. As a result, Alfred Pule was forced to resign.

On the same board sat Elizabeth Ellul. Her husband works as an architect for Joe Portelli. But, again, the conflict of interest was not declared.

Quite apart from conflicts of interest which are wilful breaches of rules, the best tool in the opaque wielding of power in the context of what should be a rule-based system is the undermining of those rules by design.

Consider again Elizabeth Ellul’s vote to approve Joseph Portelli’s decadent villa in pristine countryside. The decision was based on rules that were under pressure from the press after the vote, rules which she admitted needed updating. Her defence then was that with the tools she was given, she could not do much better. Except she had written those rules. Just three years earlier.

This has been happening all over the business of the Planning Authority. Year after year, they admitted that policies on petrol stations needed updating. Year after year, they processed and approved applications for petrol stations without a policy in place that could have, would have, should have restricted them. Petrol stations are just an obvious example. The problem is far more structural, endemic within the system.

When Labour came to power in 2013, they instructed the Planning Authority to revise Local Plans. These documents, in principle, should guide land use and place every single plot of land into a broader, logical context. The revisions were ready by 2015, but they were never published. They’ve been gathering dust since, while the Planning Authority churns out permits in breach of existing Local Plans because, of course, the existing Plans are irrelevant purely because they’re a quarter of a century old, and this is now an altogether different country.

When the departure from the Plans is so radical that the Planning Authority cannot bring itself to approve it, people with the right sort of access get Ministers to fix the problem for them. So we’re back to Yorgen Fenech. One fine morning, part-owner of industrial land in Mrieħel, he walks into the office of Michael Farrugia, then Minister for Planning. A coffee and a handshake later, he walks out part-owner of land on which a row of sky-scrapers bang in the middle of the island could be, and are now being, built.

The Planning Authority is, then, entirely misnomered.

There is no “planning”. Old plans are ignored, and new plans are mostly shelved. The plans that do see the light of day are either too slack to have any meaningful use or published too late, slamming the gate long after the horses have bolted.

Consider an interview given recently by Johann Buttigieg’s successor, Martin Saliba. He rebranded the uglification of Malta as its modernisation, and he legitimised the greed of over-development as an expression of people’s sacred and democratic right to do as they please with their property, no matter the consequences.

That perhaps is the best illustration of the fact that there is no “authority” either, certainly not in the sense of the competence and powers of a State-agency at arms’ length from elected officials that takes decisions based on public and objective rules and, when this is helpful, based on precedent. Instead, the real authority resides with the Yorgen Fenechs the Silvio Debonos and the Joe Portellis of this world (the list is not exhaustive, but it doesn’t get much longer either) who pull the strings of the Matthew Paces, the Elizabeth Elluls and the Michael Farrugias of this, same, world (the list is not exhaustive but it doesn’t get much longer either).

What’s happening here is what I called in the March 2019 article I published on my blog Truth Be Told, ‘The Sack of Malta’.

I use the term ‘Sack of Malta’ advisedly because it replicates the model of the sack of Palermo in the 1950s and 1960s. Then, the elegant Baroque city, surrounded by citrus groves and a picture-perfect landscape, was transformed into the haphazard concrete jungle that gives Sicilians a sickening melancholy to this day.

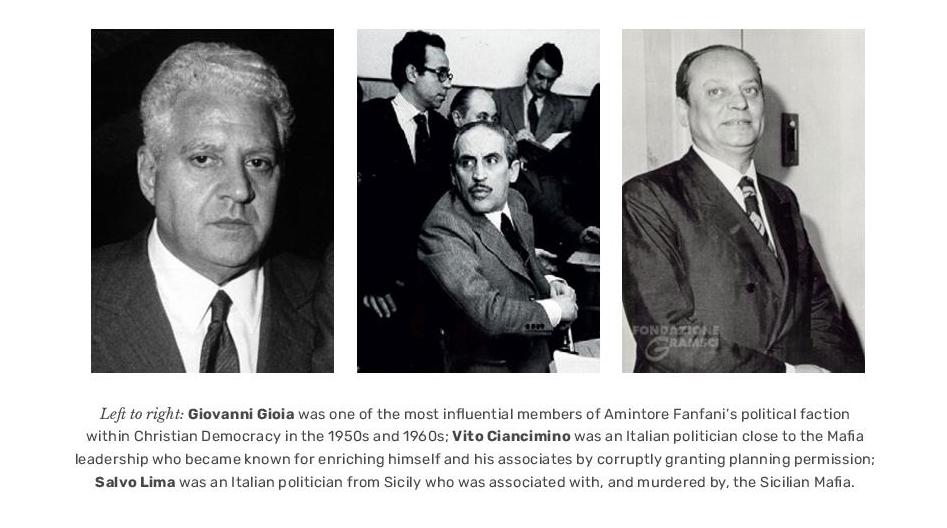

It was organised by names you’ve heard of because eventually they died in disgrace or were gunned down in the street when things got sour. But Giovanni Gioia, Salvo Lima and Vito Ciancimino organised the three-way arrangement between town planners, the mafia and the Democrazia Cristiana to facilitate a “building boom,” the corrupt consolidation concrete of the cash reserves accumulated by crime and corruption.

The draft town plan for Palermo, full of hifalutin conservation principles and careful planning, was published in 1954. It was dragged through the drudgery of public consultation, with hundreds of amendments in response to private applications from citizens, and many adjustments to accommodate the claims made by local DC politicians on behalf of constituents, most of them Mafiosi.

Multiple versions were published in 1956 and 1959; all the while, public building contracts and permits for concrete edifices were issued until a final, binding version of the town plan was published as approved law in 1962.

In the meantime, ad hoc permits for demolition of elegant buildings from the late 19th and early 20th century were rushed through the town council often days before the buildings 50th birthday when they would have been automatically scheduled for conservation.

But by then, the disaster had been completed, and the conspiracy was conducted by design. Shares of public expenses and the returns from the development activities found their way back into the pockets of the politicians who facilitated them and the political party they organised like a freemasonry lodge.

In the process, they brought out into the open cash generated by the mafia in the rapid criminal boom after the hardship of the years of Fascism and war.

Of course, the real victims of this conspiracy are the generations of Palermitani and Sicilians that inherited one of the finest cities of the Mediterranean, ruined by random, haphazard “development”, as great a misnomer as “palazzo”.

This is what is happening to us now, in front of our very eyes.