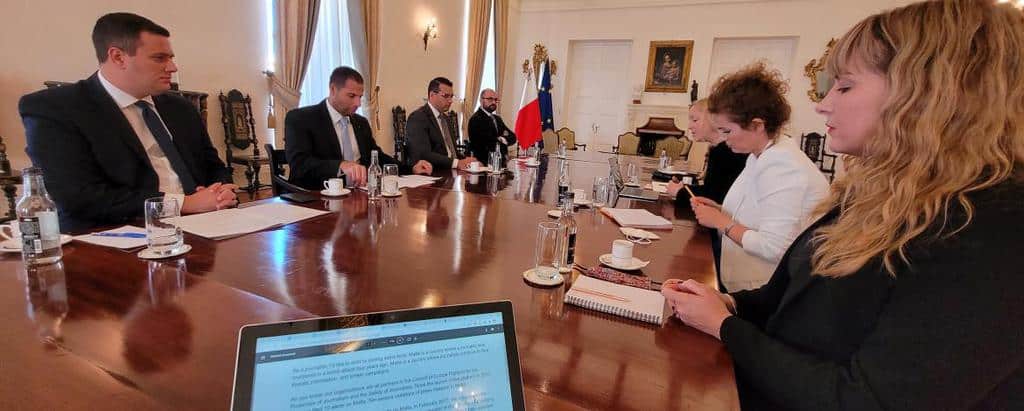

In a reply to Opposition MP Claudette Buttigieg, Prime Minister Robert Abela confirmed that he’s been working for months on drafting an anti-SLAPP law “to strengthen the protection of journalists”.

The MP asked the question because just recently the PM said the law was days away from being presented to Parliament. Where’s the law then? Where’s the draft?

Robert Abela said he was consulting the Institute for Maltese Journalists, the Caruana Galizia family and international institutions. Those “consultations” he said were “at an advanced stage and a bill will be presented to Parliament imminently.”

All this looks just as it should be. It isn’t.

Laws to protect journalists do not only concern journalists. They are of interest to the entire country because this is about the protection of people’s right to be informed by journalists who can act freely.

In other words, this is not some specialised or technical law to be discussed with a narrow interest group. This is rather a crucial component of, hopefully an improvement to, our democratic design. This is a law that regulates and protects the most basic freedom of all, the freedom to know.

The PM’s patronising reassurances give me no comfort. I panic when I hear Robert Abela say “he’s been working for months” on something nobody has seen, especially since he and his government spent years saying such a law would be impossible, even illegal considering our international obligations.

I couldn’t be happier that he’s speaking to the IĠM and to the Daphne Caruana Galizia family. They bring expertise and direct professional experience to the discussion.

But that’s not enough. This is the sort of law that should appropriately be published in the form of a White Paper before it goes to Parliament so that people can openly speak their mind and we can have a proper, mature, and democratic discussion about a proper, mature, and democratic law.

Private discussions held with specific organisations or people are all well and good at the drafting stage. But consultations should happen openly and transparently. I am interested to hear what the IĠM and Daphne’s family (and others) have to say about a draft (a draft they and everyone else would have seen) before it goes to Parliament by when practically nothing can be done about it.

I do not want to promote myself as an expert because I’m not. I’m interested in an anti-SLAPP law because I’d like to test the draft against my experience.

Would the law have protected me from the threats from Joseph Muscat, Michelle Muscat, Chris Cardona, and Konrad Mizzi when they hired a UK law firm to try to block the publication of a book I wrote with two colleagues?

Would the law have protected me from Yorgen Fenech’s plans to file a ruinous lawsuit against me in the UK?

Would the law protect me now that I’m waiting for a decision on my appeal from a ruling against me by a Bulgarian court, sought and obtained by the owner of Satabank?

Would the law protect me from the frivolous and vexatious lawsuits I have had to defend in Malta filed by people who wanted to achieve nothing more than my silence?

I am far from alone in this situation. Maltese journalists are vulnerable to this sort of libel tourism especially when they cover stories concerning powerful, well-resourced people.

Robert Abela’s predecessor was one of those “powerful, well-resourced people”. Robert Abela can at any time be in a situation where he would want to have access to an arsenal of resources to prevent journalists from reporting on him. He may already be in that situation. How can he be best placed to draft the law that disarms him?

Also is the list, Robert Abela gave Claudette Buttigieg, of people he is consulting about anti-SLAPP complete? Is he also having undeclared conversations with powerful, well-resourced people keen to still have a way to hound journalists into dark caves?

This process must be transparent if it is to be trusted at all. Otherwise, it’ll be another one of the many “democratic reforms” introduced by this government as ruses that achieve nothing beyond its legitimisation and the false impression that anything ever changes here.