New York’s Columbia University has included the case brought in Malta against Minister Owen Bonnici for the removal of flowers and candles and protest messages and banners from the Great Siege Memorial in front of the court building in its database of human rights courts decisions that “expand free expression”.

This is the second case brought in Malta that has made it to the Columbia “Global Freedom of Expression” database after the case brought against the Planning Authority by Daphne Caruana Galizia’s family for the removal of a protest banner on their property in Old Bakery Street, Valletta.

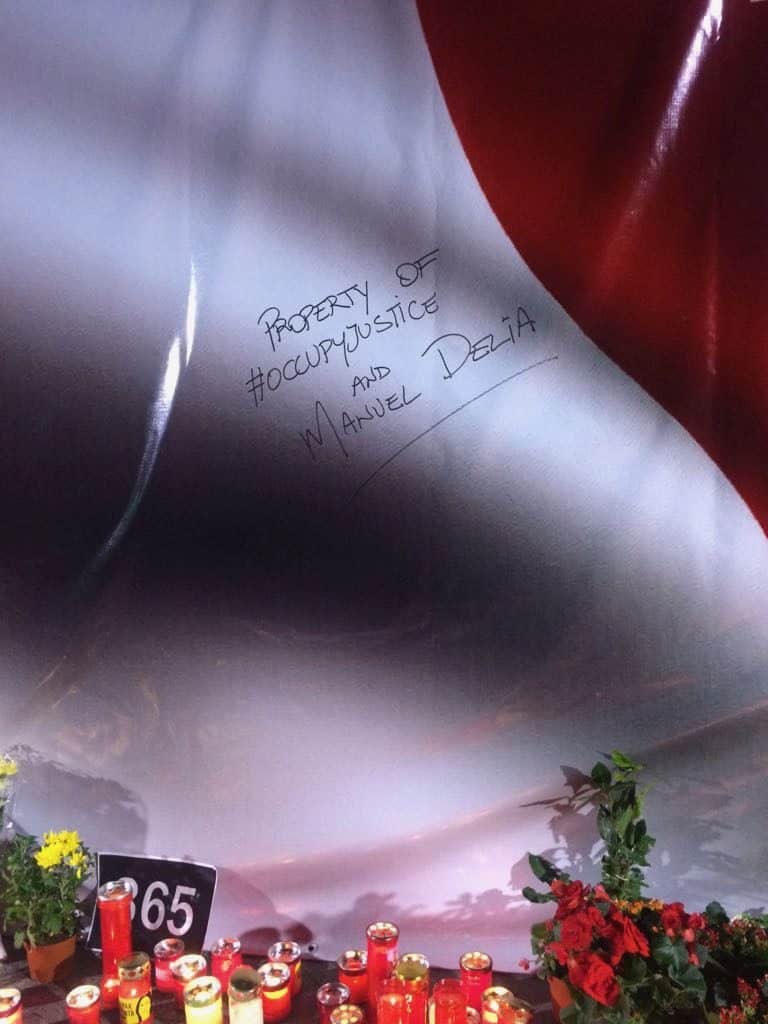

The case known as Delia v. Minister for Justice of Malta Owen Bonnici “expands expression for several reasons,” say the findings of the Global Freedom of Expression researchers.

The Columbia University analysis finds that the Court declared that the objects used in front of the national monument in Valletta, namely flowers, candles and other items were protest objects and served a protest purpose aimed at reminding the public and the authorities the call for justice.

The Court’s decision expands the right to protest by declaring that placing a banner, flowers, candles and other objects in front of a national monument calling for justice for the murder of killed journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was a form of expression protected under Article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights and Article 41 of the Constitution of Malta.

Thirdly, the Court set another important precedent for the right of protesters in Malta recognising that the removal of the protest objects had the intention to hinder not only the plaintiff’s (Manuel Delia) right to freedom of expression but that of others with his same opinion.

In July 2019, the same Court delivered another landmark ruling in relation to a banner placed by the family of Daphne Caruana Galizia questioning authorities about impunity for the killing of the journalist. In both cases, the Court considered the decision of the Minister of Justice, in the first case, and of the Planning Authority, in the second one, as arbitrary and in violation of the protester’s and family’s respectively right to freedom of expression.

Fourthly, the Court expands the right to protest by recognising that although protests may have repercussions that annoy the State and the public opinion of those who do not share the protest purpose nor its form, this sentiment does not meet the necessity test and, therefore, is not sufficient to render the removal of the protest objects.

The review of the 115-page court decision was possible after the Daphne Caruana Galizia foundation funded the costs of its English translation.