The appointment of Alex Dalli to the directorship of the prison has introduced an element that is strongly discouraged by worldwide experts on prison administration. Alex Dalli is a retired colonel in the army and experts recommend that prisons are run by civilians not members or former members of disciplinary forces.

His rule which will start its third year in June has also been characterised by problematic changes to the medical care given to prison inmates, particularly mental health care. This website is informed that he was a principal driver of these changes.

Consider these two cases that ended in deaths under Mr Dalli’s watch.

Ben Ali Wahid Ben Hassine died on 1 December 2019. He was serving a life sentence after having been convicted of multiple murders in 1988. When he was first sentenced he had every reason to expect he would spend the rest of his days in prison.

A life sentence is as good a reason for despair as any. When sentence starts and the metal doors clang shut many people would lose the will to live. Indeed, most prison suicides happen in the first three days of a long sentence.

But Wahid Ben Ali was made of sterner stuff. He was educated as a nurse and understood his own health and how to take care of it. And though he was far from his native country, members of his family visited him whenever they could. He had a lifeline to the world outside even if he had no hope of experiencing it for himself.

That hope changed two years ago. He had served almost three decades of his life sentence when through his lawyer he won the right to apply for release on parole at some point in his life.

In 2017, the courts recognised that it was the fundamental human right of anyone serving a life sentence that a mechanism would exist that could consider revising that sentence, possibly reducing it or granting parole. The government ignored that decision for a while but Wahid Ben Ali kept up the fight and he acquired another court order to have the first sentence implemented.

When the parole board finally heard his application, it was rejected with no possibility of review for 5 years. In November 2018, the courts refused him judicial review of that decision.

You might expect that decision to have been crushing for Wahid Ben Ali’s morale but you do need to put everything in context. The inmate lived through 25 years of a life-sentence earning a reputation of intelligence and relative stability. He did have bouts of depression in that time which he would recognise and ask to have treated. He spent some time at the secure unit of the mental hospital during his sentence, checking himself out when he felt better.

It can be argued that in 2019 his reason for hope of ever seeing life on the outside again was greater than it had ever been before. He earned the right to apply for parole and though his first request was rejected, the parole board handed down deliverables he would need to work on so that his case might be reconsidered in 2023. These were not insurmountable targets.

In November 2019, Wahid Ben Ali was probably depressed. This time, however, he did not ask to be treated at Mount Carmel Hospital. This was unusual for him. It would also prove fatal.

On 1 December he poisoned himself with paint solvent, a chemical which one way or another was allowed in his cell.

Consider now the case of Noel Calleja who died on 13 March 2019. Noel Calleja came to prominence in September 2012 when the police sought to arrest him after he stabbed his girlfriend with a screwdriver. The fact that he had profound psychiatric problems became clear to everyone when to avoid the police he climbed to the roof of a building in Paola and sat on a horizontal pole for four hours threatening to fling himself to death.

Noel Calleja had clearly severe and pervasive mental illness. He had been a patient of the ‘regular part’ of Mount Carmel Hospital many times. And he was referred to the forensic unit of the hospital several times during his imprisonment as well.

In March 2018, almost six years after he first stabbed his girlfriend he hurt her again throwing acid at her out of morbid, pathological jealousy. Again, he was arrested and again he was referred for treatment at the Mount Carmel Hospital.

Sources tell this website that around February 2019 the director of prisons Alex Dalli visited Noel Calleja in the secure wing of the hospital. He also apparently has persuasive skills: it appears he persuaded Noel Calleja to discharge himself from Mount Carmel in spite of his doctors’ recommendation to stay.

He checked himself out of hospital on 1 March 2019. Thirteen days later he used a prison blanket to hang himself in prison.

These are two of a number of other deaths in prison over this period.

The circumstances of these deaths appear to be symptomatic of a broader pattern of behaviour where the recommendations of psychiatrists who identify suicidal ideation and rumination in their patients appear not to lead to the doctors expect. These professionals expect that their patients are transferred to a mental hospital where they can be treated to avoid more self-harm or even suicide.

But in some cases, they aren’t. Even if the prisoners had already agreed with the doctor that they needed care. When a patient agrees to be hospitalised, the doctor cannot force their transfer to hospital as sectioning rules under the Mental Health Act do not apply in cases of voluntary hospitalisation. That would mean that someone else after the doctor may be persuading the prisoners not to go to hospital. Or they may be preventing them from following their doctor’s advice.

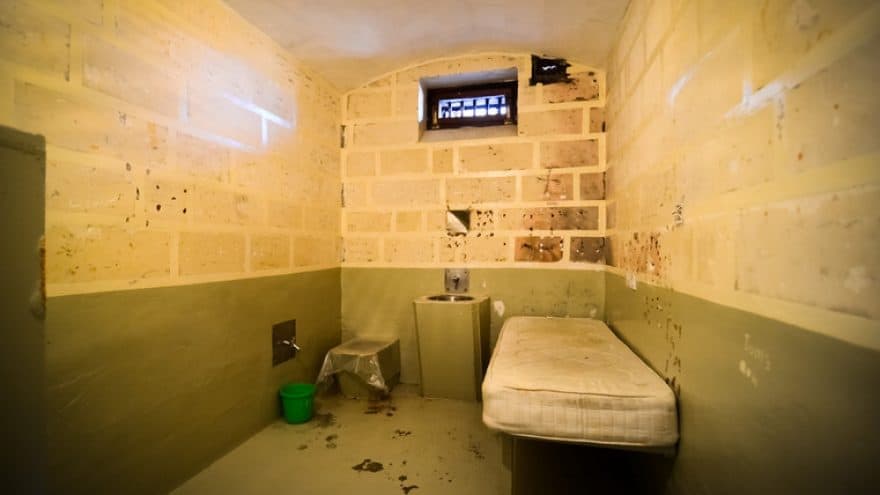

Other sources suggest that the prison authorities have used disciplinary measures to punish mental health symptoms as if these were infractions of prison rules. At least one patient is believed to have been confined for a month in solitary in the sole company of a metal bed because they were depressed. Their situation is not believed to have improved.

The intuitive reaction of most people to this story is probably collective indifference. Wahid Ben Ali was serving a life sentence for some of the most heinous murders in local living memory. Noel Calleja was far from the only victim of his mental illness. He was violent and caused his victim pain and suffering over a long period of time.

But they were in the custody of the state. As such they were our collective responsibility. Our membership of the civilised world demands of us that we treat even the worst criminals humanely and that we seek to preserve their lives even as we punish them, treat them or were possible seek to rehabilitate them.

These incidents are glaring clues that we may be failing in this regard.