Every minister wants to be remembered for having made a difference. In most sectors however ministers appreciate there are limits to their revolutions. Consider the health sector for example. Ministers will want to be remembered for extending national coverage say, or opening a new hospital wing. They will fight for the funding, hound the administrators, squeeze the contractors and take many photos proudly unveiling the plaque at the opening.

But most health ministers know that their legacy will not include reforming the procedure for open heart surgery or discovering the cure for cancer.

Ministers know that though the health department reports to them, scientific discovery or administering health to the afflicted is up to the professionals they recruit. We wouldn’t trust a health minister for long if they insist on personally manning the operating theatre.

The health department is an obvious example. There will be degrees of territorial encroachments in other less obvious areas like planning and development say, or policing and national defence.

But nowhere is that intrusion more obvious and more tragic than in the education sector. Teachers have been jerked around by major reforms for decades and the more they’re shaken about the more they’re stuck in the same place.

Every new government minister that shows up conceives some grand scheme, a turning of the page, a radical overhaul. They’re justified in wishing for change. Since success should only be measured by outcome, our education service fails in many respects.

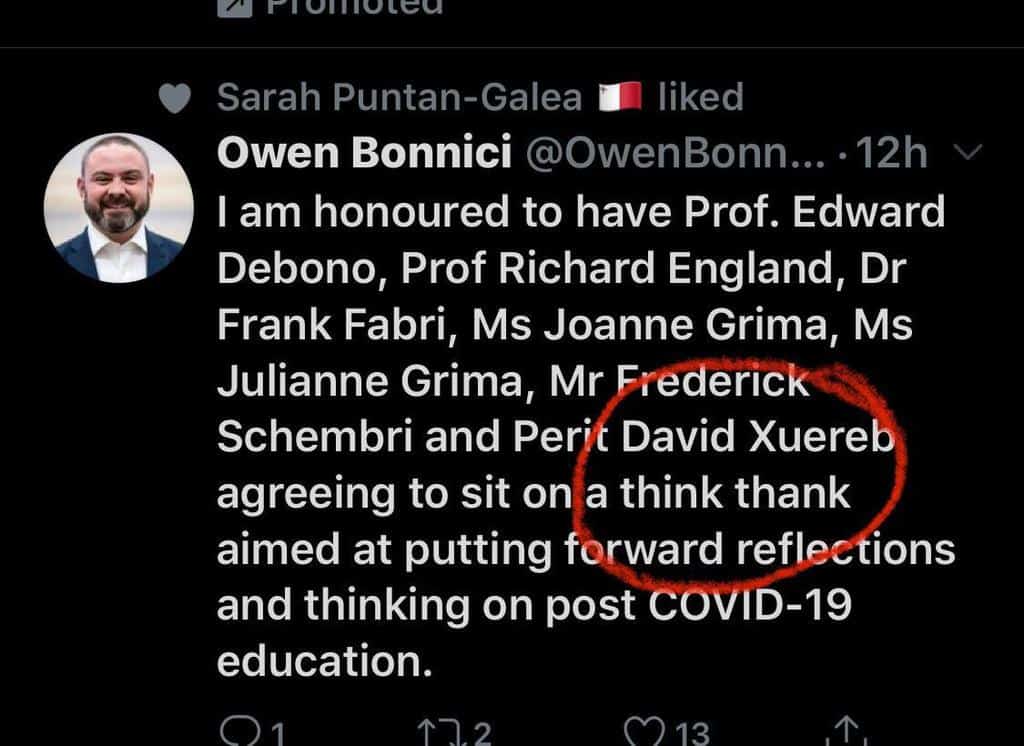

We all see this. This is why Owen Bonnici feels he can speak of “blue sky thinking” for education. From Malta Today’s report: “The Education Minister said on Wednesday that the think thank (sic) is being instructed to apply ‘blue sky thinking’, and brainstorm ideas without considering barriers such as financial constraints. ‘We don’t want [the think thank] to ask why but why not?,’ Bonnici said.”

You won’t have blue sky thinking in government advisory units discussing heart disease. The notion of starting from scratch would be abhorrent. The notion of having such a discussion without anyone actually professionally qualified and published in the area would be laughed off.

But Owen Bonnici felt he could set up a committee made of officials in his department and people who – though competent in their fields, no doubt – have not had a day of pause from their own professional lives to appreciate the science, the research and the knowledge in the field they’ve been asked to consult about.

The first ‘why not?’ then that these people will be asking is ‘why not throw away all the scientific discovery made in the history of pedagogy anywhere by anyone at any time and sit down instead to reinvent education, fancying ourselves Aristotle at the founding meeting of his Academy?’

This is ridiculous. The government should not be setting up think tanks (or think thanks for that matter) especially if they place on them senior administrators that report to them.

The government should be listening to think tanks, not appointing them. We have one in the field of education. We’ve had it for some time. It’s called the Faculty of Education at the University of Malta. If the government feels people there are too jaded, too frustrated, too exhausted to produce fresh ideas they can stir things up by complementing their advice and recommendations with other expert views. There are tens of thousands of researchers and academics in the field of education anywhere in the world.

The government may prefer a school of thought over others but whatever choice they make will at least be framed in accepted standards for the trade, founded on research and knowledge, scrutinised by peers and tried and tested somewhere.

You can almost hear the spines of teachers rattle at the sound of yet another minister saying they want to “change everything”. But can you imagine what they must feel when they hear a minister say that his plan is to replace everything with anything.

It’s true that what we have needs changing but change is only worthwhile if it is for the better.

Also the reward from past reforms is usually very limited because the weakness is not usually in drawing up ideas from a blue sky agenda. The weakness is in implementing those ideas thoroughly and giving them the time to percolate the system. By the time green shoots start appearing a new minister is in and the furthest thing from their mind is cultivating and nurturing the legacy of their predecessors and make sure their reforms work.

Instead a new minister will focus on what they can be remembered for.

Can you imagine cancer research conducted in this way, starting afresh every time a new minister is appointed? Don’t worry. This cyclical going-nowhere management style is not applied to medicine. It’s only really used for something far less important: the education of our children and the tools in the hands of future generations to live a full life.

Why not?