The below podcast is an adaptation of a speech I delivered this morning at the invitation of KSU at the launch of their Erasmus+ project with the title ‘Democracy Derailed?’ If you prefer, scroll down to read the text of the speech instead.

Chair,

Mr President,

Thank you for inviting me to share some thoughts with you today.

I was in my early teens when the communist regimes that I mostly understood from gung-ho American movies collapsed, giving way in most cases to fledgling democracies.

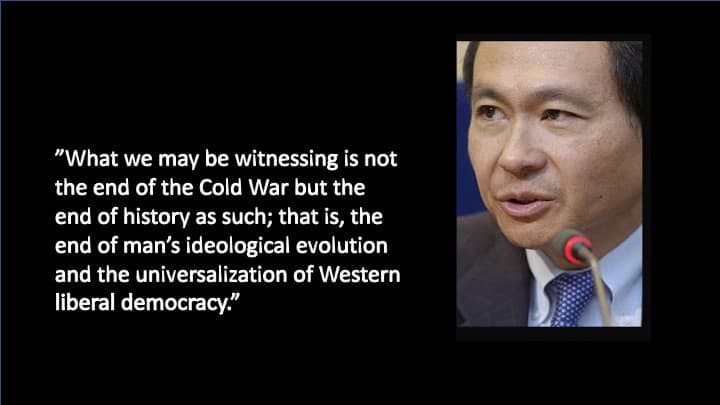

Later I would come across the writings of Francis Fukuyama.

A picture of an Asian man featured on a publication of Malta’s Nationalist Party sometime in 1994 told me at the time that I should be interested.

Fukuyama was, for a while, the Stephen Hawking of political philosophy.

In a 1989 essay, he coined the phrase ‘The End of History’, stretching the Hegelian notion that history is the linear progression of competing ideas about political organisation culminating in some Darwinian ideal. For Karl Marx, the ideal would be a hoped-for future when a Socialist sun would rise above a perfect world. For Fukuyama, the eschaton was now: no one had a better plan for a political system than liberal democracy. We got there.

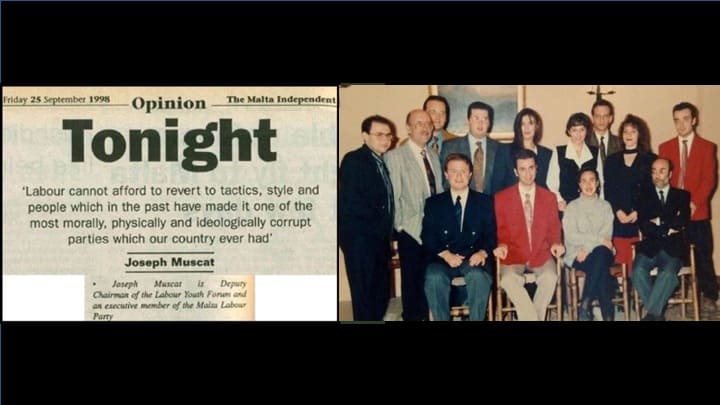

Malta went through that too. In the 1990s the Labour Party went to great lengths to distance itself from its past.

It repudiated violence and corruption in previous governments it led. “Labour cannot afford to revert to tactics, style and people which in the past have made it one of the most morally, physically and ideologically corrupt parties which our country ever had.” That’s one Joseph Muscat writing in 1998.

And then, four years after the EU referendum of 2004, the last cause of programmatic division between the two parties became redundant as both parties recognised that Malta’s membership in the EU would no longer be a matter of political controversy.

It felt like the end of history. That all that would happen after that would be the smooth alternation of political parties in government, opting between management teams like choosing players at schoolyard football. Politicians no longer needed to propose grand plans. They needed to shape up to look like effective managers.

And, perhaps more to the point, citizens were no longer expected to discern political programs and choose between grand ideas for their country. Politics became ever smaller in people’s lives. All you needed to do now, as a fully engaged and committed citizen, was focus on your career, on the money you made for yourself and your family.

The job of citizens, in this neoliberal eschaton, is to make money. And the job of the government is to get out of their way and let them do it.

As someone once said about the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers of New York, a single, violent event in Malta brought about the end of the end of history.

There had been critics of the idea that politics in Malta had graduated to a level of maturity that the population could largely afford to ignore it. But they sounded shrill and cynical. These Cassandras were marginalised and largely ignored. Until one of them, by far the most prominent, was killed in a car bomb on 16 October 2017 forcing us to stop and think why that happened.

A prosperous EU member state with full employment, that imported labour like it had struck gold looked to all like it would go nowhere but up and up. And yet, on a quiet, hot October afternoon, a violent explosion reminiscent of a troubled and conflicted war zone, challenged that generic impression.

How could this happen? The killing of Daphne Caruana Galizia is not the entirety of Malta’s contemporary history. But no understanding of the country we live in today is possible without accounting for it.

Today’s discussion is not an analysis of that event, though, as we shall see, it is impossible and undesirable to stray too far away from it. But the roar of that ball of fire raises the question that this series of events is asking rhetorically in its heading: is our democracy off its tracks?

I cannot give a full answer to that question within the time I have today.

I will try to list some of the reasons why I believe democracy is in a precarious state, that in some respects our expectations of it are already unrealistic and that the smug indifference with which we have treated this treasure when we all assumed it had done its job can be the cause of many regrets for coming generations.

The challenges to our democracy have been picked up by statistical indicators published by Bertelsmann Stiftung, Varieties of Democracy, and the Economist Intelligence Unit which relegated Malta to the status of ‘flawed democracy’ in 2019, ranking 26th overall in the world from 165 countries. Malta’s score, 7.95, was its lowest ever.

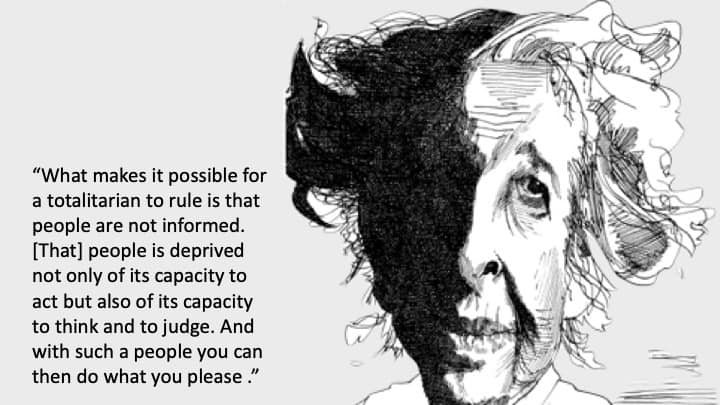

To many of us living with it, this measured degeneration is imperceptible. A word of warning: tyrannies are perfectly capable of looking like democracy even as they subvert it.

There are superficial characteristics of democracy that tyranny can happily live with. General elections are held in Russia. Opposition parties sit in the Chinese equivalent of Parliament. You can get justice for a personal dispute in a Belarus court. None of us, I think, would describe these countries as democracies.

Let us look at our own.

Elections in this country are, at face value, free and fair. Participation is high and access to the ballot booth is guaranteed. Private ownership of the media is protected. Administrative failures can be contested in a court of law and on matters of human rights citizens have unhindered recourse to an outside court. Contesting elections is largely open to all and the financial barriers to nomination are not prohibitive.

Citizen participation in the electoral rituals of a polity is no proof of democracy, however. In our case, where genuine debate is rare, where TV news is propagandistic, polemical, and often based on a tenuous relationship with the real world, citizens are hardly equipped to make an informed decision in ballots where loyalty to the team is prized above loyalty to the game.

Hannah Arendt said in an interview that “what makes it possible for a totalitarian to rule is that people are not informed. [That] people is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.” I would add that you could get that people to vote for you again and again, while you smile. And murder while you smile.

Citizen participation in the functioning of our democracy beyond participation in electoral rituals is extremely limited. Though in theory becoming a political candidate is easy, the general result does not reflect our community. The early-to-mid-career, wealthy, male, lawyer remains the dominating elite of our political life.

In part that comes from weaknesses in our institutional design. We would never imagine running this country with a part-time police department or a part-time hospital or part-time judges. And yet the chamber that writes the laws we must obey operates on a schedule, not unlike your local band club committee: around 9 hours a week. The hours and methods, the fact that Parliamentarians are paid peanuts, the entire systemic design of our Parliament, is written around the early-to-mid-career, wealthy, male, lawyer who always has somewhere else to go.

We may have to rephrase the question then. Asking if democracy is being derailed assumes it had been chugging on rails at some point. Perhaps we have been sleepwalking in stagnant chaos and what is changing now is the awakening realisation, by no means unanimous, of the depravities of corruption and illegality we have been dragged down to.

We have been educated to think that voting every 5 years means that everything that happens in between, however grey, even illicit, even illegal, is a Panglossian best of all possible worlds.

We have been trained to believe that only political parties hold a stake in democracy, recalling that elegant Italian description of their own post-war system: partitocrazia.

And some have gone so far as to try to persuade us that the principle of majority rules means that the majority can act with impunity, ignore rules, and act as it pleases. In place of rule of law, we were told, we need to submit to the rule of the majority, the tyranny of the majority.

The practical redundancy of our Parliament has material consequences on the quality of our democracy. Parliaments are important. The first thing the revolutionaries in America did was set up Congress. The French Revolutionaries formed a National Assembly in an indoor tennis court in Versailles. Before them, English Parliamentarians revolted against the King, killed him and when they got a new one to replace him reduced him to a subject of Parliament rather than the other way round.

I think it is fair to say that Parliament in Malta has been reduced to a ceremonial husk, betraying ritualistic trappings but with no material consequences. Laws aren’t written in Parliament. They’re written in government, proposed by the government and processed through Parliament purely for the legitimisation of its will. Even mad Roman Emperors who appointed their horse to the Senate did that.

If we are honest with ourselves Malta does not have a legislative branch of government. If the legislature is unable to make any difference to the intentions of the executive branch then it’s as if it weren’t there at all.

This goes beyond the job of writing the laws that the executive is supposed to fit within. It’s also about the failure of that other function of Parliament to scrutinise and restrain government conduct. The failure there is manifest.

This weakness is also reflected in other institutions that are supposed to counter-balance the executive. We are supposed to have a civil service that agnostically serves the government of the day but ensuring at all times that the government it serves acts within the law, that we have institutional memory that survives existing governments, that make sure that public services are provided without partisan favouritism or as political transactions.

Our Constitution requires engagement to the public service based on merit and without regard to personal political affiliation.

And yet the engagement of hundreds of persons of trust and the wilful removal of ironically named ‘Permanent’ secretaries upon a change of government, ensure that the intention of the Constitution is frustrated.

The capture of the judiciary with appointments governed blatantly by partisan loyalties and the appointment of favourites on regulatory agencies that are supposed to be keeping the government in check completes the discreet but hostile take-over of the Constitutional tools that are supposed to keep our democracy well within its rails.

This brings me to our relationship with our government. One thing should have shown up the naivety of suggesting this had become a mature democracy even in the heady 1990s: the persistence of clientelism. That’s the transacting of public services, policies and decisions based on private conversations between decision-makers and private individuals.

Like the business hours of Parliament, this too is designed around the needs of a class of politicians that today is successful. Voting preference is not secured by persuasion on the grounds of policy or even the promise of administrative excellence. It is instead negotiated against a favour.

A ‘favour’ is, by definition, a privilege one is not entitled to. If you could get that building permit by right, you wouldn’t need a minister to intervene on your behalf.

The intervention does not only benefit the person who is now holding a permit to build where others would not have been allowed. It also benefits the politician who by trading in influence and patronage has accumulated more authority and secured their incumbency.

The small-scale favours of a public sector job, an out-of-turn army promotion, a rule-bending building permit, and so on, are the bottom of a food-chain that rises to the large-scale transactions between big-moneyed operators and their political vassals.

In part, this too is a problem of institutional design. Our political parties are effectively unregulated. The Constitution practically ignores them. And the rules of accountability we do have are in their infancy, absurdly limited in scope, and given that political parties run the organisation that is supposed to supervise them – the Electoral Commission – utterly ineffective.

And yet political parties are the rooms where it happens. Well, they’re the room where it happens when they’re in government or they’re the waiting room where it is going to happen if they stand a chance of getting there. In that room, beyond any scrutiny or supervision, moneyed-interests transact favours with politicians, funding their campaigns and extracting out of them policy commitments, short-circuiting all forms of Parliamentary, institutional and public scrutiny.

I remember something Daphne Caruana Galizia had written. We should not be shocked at having corruption in our country. It doesn’t make us collectively bad people in and of itself. Corruption is everywhere at every level.

This year, France sentenced its former president. South Africa imprisoned one of hers. Since the Panama Papers, Pakistan imprisoned its former prime minister. Also over corruption, Israel has jailed one of its former prime ministers and he may not be the last. The Vatican is trying a senior cardinal for fraud.

What is particular here is that our attitude to corruption is corrupt. We admire it. We coalesce to vote for it. We want our politicians to be corrupt so that we can have our way when we need it.

Without a measure of moral restraint, the neoliberal principle that making money justifies itself takes us to its logical conclusion: that it doesn’t matter how we make our money.

This I think takes us to the root of the problem of the erosion of democratic life, such as it is and has been. The question no longer is whether an action is right or wrong, but whether it is profitable. It is also the point where someone like me becomes vulnerable to accusations of hypocrisy or of being holier than thou.

Consider Malta’s economic policy for the last 30 years. The economic challenges for an island State of our size are not to be underestimated. Economies of scale act against us. The lack of resources is self-evident. And our aspiration to rise above colonial servitude is not limited to the dignity of political freedom. It is ultimately the product of the desire to be wealthier.

Whatever the marketing buzzwords we choose to append to our financial services industry, this country has made it its mission to profit from our collusion with people avoiding to pay tax in their own country. The classic sophistry is that evasion is illegal but avoidance isn’t. That tax structuring, as we call it, is a-ok.

Then there’s online gambling. Whatever your stand is on an individual’s right to throw away their money at impossible odds, we have built the dependence of our prosperity on other people’s vices.

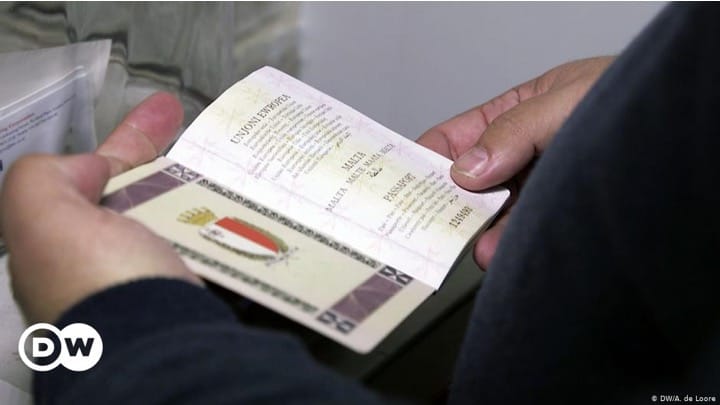

Then we sell citizenship which I find objectionable for intrinsic reasons but even on the purely utilitarian level, the entire edifice of the scheme is predicated on helping people hide the truth about who they are, where they’re from and what they’ve done there.

These are 21st century equivalents of piracy. Our answer remains the same: we need to eat. Again, there’s the amoral pretext that income, no matter its source, justifies itself.

We have taken this to extremes.

Italian organised crime has used Malta’s financial and gambling infrastructure to launder proceeds from their violent crimes and rackets.

Azerbaijani, Venezuelan, Libyan and Angolan tyrants have used Maltese banks to launder the money they embezzled from their impoverished populations.

Industrial-scale smugglers and money-launderers, and Vladimir-Putin-huggers, have used their acquired Maltese citizenship to dodge law enforcement agencies around the world.

The blood of their victims is not spilt on our soil so we can afford to ignore all of this. But that doesn’t make any of it right.

We do however suffer irreversible consequences of profit-minded amorality in public policy even here.

We are living through the sack of Malta, and a sack of Gozo is coming on in earnest. Poorly regulated construction, in any case, short-circuited by the corrupt obligations of political parties towards their faceless pay-masters, has become over time the rape and pillage of the heritage we are supposed to be custodians of for future generations.

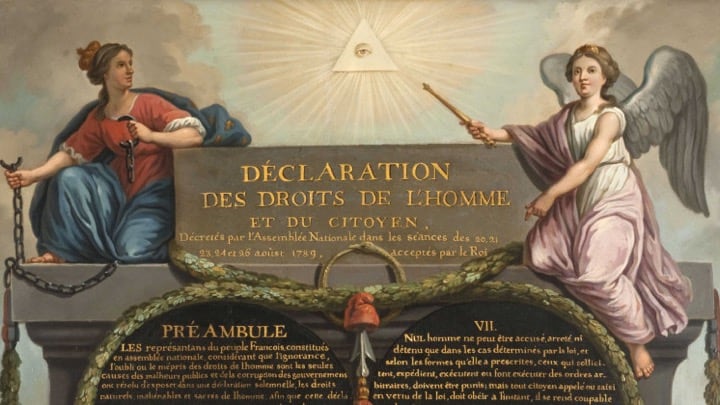

What does this have to do with democracy? Everything. Because the one thing that distinguishes democracy from all other political systems is not the right to vote or even the ability to lampoon and criticise people in power.

Democracy is different from other political systems because it is moral. Democracy requires fairness.

That starts with the notion that human rights are fundamental and universal. In 1791, the French Revolutionaries did not draft a Declaration of the Rights of French People. They drafted a Declaration of the Rights for all Men. The Americans said “we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal.” And when I meet Thomas Jefferson I’ll compel him to include women in the sequel.

The universal application of rights is a test that our so-called democracy keeps failing. We have developed a collective immunity to reports of torture and unexplained deaths in civil prisons.

We condone near indefinite detention without charge for people whose crime is escaping the indignity of slavery, war and starvation. We prioritise our fear of infection from a virus over our civilising obligation of rescuing the lives of people drowning at sea.

When we do that we play hard and fast with the very basis of democracy: the moral imperative of protecting the right of every human being to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The morality of democracy imposes on us the imperative of solidarity, of ensuring no one is left by the wayside because of whatever vulnerability they are afflicted with. And yet this has become a country that is obsessed with keeping its taxation levels low.

That the idea of increasing the tax bill on wealthier people is practically anathematic even as we see a widening gulf between the richest and the poorest, and the re-emergence of endemic illnesses this country had overcome in the past, like homelessness and lack of functional literacy.

The morality of democracy imposes on us concern beyond the interests of the present. It requires us to imagine the lives of people who will live in the houses we will die in. And yet the here and now are the meters of policy and public conduct in the way we relate to our environment, our natural resources and the climate emergency.

Morality comes with conscience and in the life of the community, that role is served by journalists, artists, writers, satirists, playwrights, poets, and students: the people who hold up the mirror to society pointing out its warts. The methods of totalitarianism are used as a benchmark to suggest that compared with how the Nazis and the Soviets ran their countries, speech in a place like Malta is as free as one can imagine it to be.

That is an argumentum ad absurdum, a fallacy that compares reality with an extreme example to dismiss it as untrue. There are balls chained to the ankles of free speech in this country and the suggestion they do not exist is one of those balls.

The Council of Europe’s platform for media freedom and safety of journalists has listed Malta as a “country of exceptional concern” when it comes to press freedom in its 2020 annual report. The “concern” also came about due to media freedom alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 together with an observation from the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe which noted “a series of fundamental weaknesses in Malta’s system of checks and balances… seriously undermining the rule of law.”

The critics of this society are lampooned as witches or targeted as traitors or holier than thou hypocritical puritans. We are paraded as strawmen, our inevitable weaknesses and personal errors used to disqualify us from having a critical opinion.

Every charge is deflected with whataboutism. Every wrongdoing exposed is mitigated, if not justified, by the odd excuse that everybody does it. Every inquiry, every finding, every conviction, severed from its logical consequences with the scythes of distraction, of insult, and of propaganda.

I use the passive voice but there are people doing this. The Daphne Caruana Galizia inquiry documented and denounced an entire trolling industry with its headquarters at the office of Malta’s chief executive.

Journalism here is starved of resources. Party-owned media do not count. The resources they have, fund propaganda, not journalism, no matter what they choose to call it. The economic vulnerability of what’s left of the free press exposes it to the same risk of compromise and corruption as political parties, submitted to the same moneyed-interests that not only get to decide what happens to this country but also what can and cannot be criticised about it.

Ultimately that defining moment in history that was the 16 October 2017 tells us that if any of us go deep enough in this dark cave we blindly waddle in, we’ll be stepping on the live wire that took Daphne Caruana Galizia out of the way.

The morality of democracy requires transparency. It is written in the contract between the individual, inherently endowed with inalienable rights, and the community where the individual lives. The sovereignty that rightly belongs to the individual is delegated to the State, the existence of which is justified by the simple fact that the State must act in the interest of the community without infringing on the rights of the individual.

Do we have that? On the surface, yes.

But lurking beneath that surface are the tentacles of a state within the State: there’s a mafia that gives no account of itself, is unconcerned with rights and individuals, even the individuals that work for it. There’s a piovra that justifies its existence by the money, status and power it accumulates; that justifies its existence by its existence itself.

And for a long time it quivered its snake-like tentacles unchecked. The Venice Commission surveyed the state of Malta’s democracy in December 2018 and recalled that “the media and civil society are essential for democracy in any state. Their role as watchdogs is an indispensable precondition for democracy in any state and for the accountability of government. The delegation of the Venice Commission had the impression that in Malta the media and civil society have difficulty in living up to these needs. Some interlocutors of the Commission even referred to a prevailing ‘law of omertà’.”

Notice how uncomfortable political parties are with the mere existence of non-partisan but highly political NGOs like Aditus, Moviment Graffitti, the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation, and Repubblika. And notice the self-censorship that sort of expectation creates, best reflected perhaps in the unnecessary agonising over speaking their minds that some student organisations went through when KSU invited them to endorse their rational and sensible reaction to the Daphne Caruana Galizia inquiry.

Political parties find the mere existence of political but non-partisan organisations inconsistent with the expectation that we unquestioningly accept that the tyranny of every day is the democracy we deserve.

Democracy derailed? That may be the wrong question. How do we put this, whatever it is we have, on the rails which would carry us to something we would be able to call democracy?

Do not give in to despair. On the shelves of our country, gathering dust, are the underutilised tools of democratic life that forever have envied the much-abused voting document.

There’s the right of protest, the right to disobey, the right to defy and resist. There’s the solidarity of speaking for the silenced and the vulnerable: migrants on land or still at sea, the poor and the soon to be impoverished, detainees and prisoners.

And even in a secular world, there’s the option of leading by example. Of pulling down the pursuit of wealth ranking it behind the conservation and renewal of our environment, the protection of the vulnerable and the pursuit of justice wherever it is denied.

Remember, rights are not given. They are asserted. I am reminded of a friend of mine, Ann De Marco, who for three years went every day to place flowers and candles at the Great Siege Memorial in Valletta in furtherance of her protest about the failure of the State to provide justice in the case of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Every day the flowers she put were taken away. At times she must have felt like Sisyphus pushing a boulder uphill in vain. But almost alone, this woman, who for the first 60 years of her life never spoke in public, reduced the entire State to the real Sisyphus of this story as its hapless officials removed her protest every day in vain, only for her to put it back there. Just as she wanted it.

That’s democracy. Power is never shared by the powerful. It is grasped from their grip by the powerless.

In a democracy there remain the tools of thought: the written and spoken word, visual and performance art, poetry, and dance. All these are packaging for the core ingredient that no democracy can subsist without: truth.

The truth about Malta’s democracy? Corruption is real. A journalist who exposed it was killed for it. The corrupt tried to get away with it. Some of them were forced to resign in disgrace, overwhelmed by a snowball that started as a pebble pushed downhill by civil society. But justice has not yet been served.

Let’s face up to that truth. The rest will follow.

History is back. And it tells the story of how we struggle our way back to democracy worthy of that name.