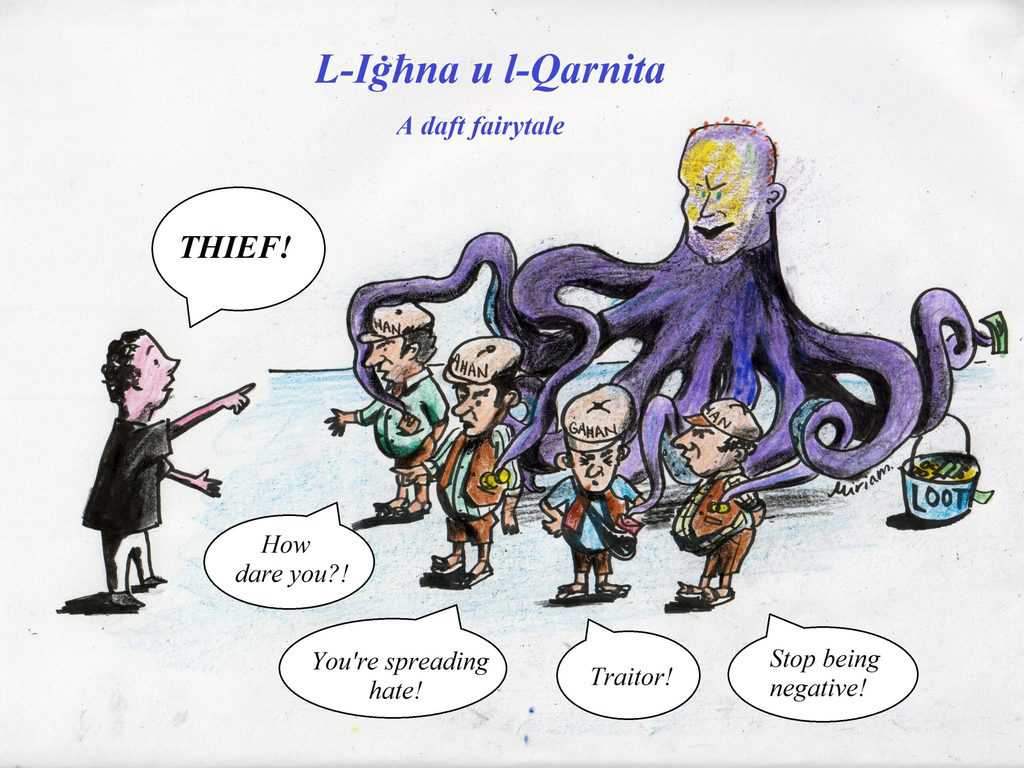

I live and work in Brussels and I draw satirical cartoons on a range of subjects which I post on Facebook. Following the cyberbullying attack sparked by my cartoon depicting Michelle Muscat as a siren and Joseph Muscat as an octopus, posted on Facebook last week, a lot of people came to speak to me expressing their support, both friends and strangers, to whom I am thankful. However, our general solidarity in this situation, as much as appreciated, still leaves us feeling pretty much helpless when up against the prevailing sea of senselessness that washes over everything else like a huge, murky wave. This is rather depressing, almost tragicomic, as Maltese society tends to be.

The thing is that I am not surprised, and barely shocked. In Malta such behaviour, deemed unquestionably wrong in democratic societies, is so common that it is normalised. It has happened to me previously when I spoke my mind publicly, and it has happened to so many other activists and even private people simply voicing their opinion on social media. During the protests following Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder in which I was also active, I remember FB accounts playing up and messenger chats freezing. But it is not normal that it is normalised.

I would like to specify that the bullying over my cartoon didn’t only involve receiving hate comments, but also having my personal FB profile shared to FB groups, deliberately exposing where I work and live and asking people to report me en masse to the authorities and to FB. My personal FB account and page have consequently been temporarily blocked after being seemingly reported by an army of trolls. This shows a deliberate method of targeting government critics with intimidation and hate speech, with a clear intention of threatening their personal and professional lives. Many people approached me telling me they had also been harassed and blocked from Facebook by the same trolls, so this is systematic not incidental.

What is worrying is that these trolls justify their hate speech and bullying, which are crimes, by equating them with criticism of public figures by activists and journalists, which is a democratic right. This betrays a total lack of comprehension of both notions. When criticising a politician or a public figure who is accountable for their service to the public, one is criticising their work and its fruit not attacking them personally for merely expressing their view. That this keeps repeating itself even after our country experienced the terrible murder of a journalist is frankly horrifying and very discouraging. The fact that Daphne Caruana Galizia was brought up in some of the hate comments attacking me, supposedly as an example of justified reciprocated hatred, is chilling.

Malta also happens to have recently jumped from being a conservative society that blindly followed religion and tradition to becoming a superficially liberated one left with a moral lacuna due to which it remains infantile and passive. It is sad that Maltese people remain subservient to their politicians rather than holding them accountable for the service they should be rendering us, their electorate. If not even the murder of a journalist has shaken people up, there is an urgent need for improving education, awareness-raising and laws on free speech and critical thought in Malta. Autonomous and critical thought should become the norm and anything that threatens and counters it should instantly and unquestionably be perceived as jarring.

Most people seem not to feel the motivation or even the need to speak up or be critical, and the few who do are being made to feel unsafe to speak. In the numbing days and weeks following Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder, I remember being stunned to see most people avoid the matter in conversations and go on with their social activities as if nothing had happened, while I felt powerless and at a loss faced with such a tragic and violent event. The passive silence was sickening and something I couldn’t handle, even if I understand most might have been feeling equally dazed.

Of course, it doesn’t help when the government itself employs such newspeak, as referring to anyone who calls out corruption as a traitor. Actions and measures that are supposedly being taken to address the problem, such as the upcoming Conference on ‘Combating and Preventing Hate Speech’ hosted by Owen Bonnici, of all people, seem to be nothing but cosmetic, for the sake of dealing with mounting international pressure rather than out of any real understanding of the issue or commitment to it.

Journalists who are sharp and critical enough to be inconvenient to the government feel forced to leave the national TV station, which acts as a neutralising sheen for any of the government’s blunders. Programmes with a minimal amount of political satire disappear from the agenda to be replaced by adequately bland ones to keep the masses dormant. The police are dragging their feet to prosecute evidently corrupt figures related to a scandalous case that should have been addressed with the utmost seriousness and urgency.

The fact that all of this is so familiar to us that we have learnt to live with it is enough to leave us disenchanted by Maltese society and its prospects, by those who blindly parrot corrupt politicians, and the silent bystanders who isolate the few who voice the truth. A society in which individuals are not educated and encouraged to have a mind of their own, but scorned and mocked for it, is one which does not foster innovation, entrepreneurship, independent thought and creativity.

Not much can sprout in such an environment, and such a society is a stagnant and toxic one. It is, unfortunately, no wonder that the big majority of Maltese youth wish to leave Malta for good, and that Maltese expats like myself tend to stay away. We have become used to lowering our expectations and having to be content with mediocrity, at best, as we end up starting to question whether we are insane.

But we have to remember, also by looking beyond our shores, that we are not. That we should expect better, that we do deserve more, that a better society can exist.