I keep going back to the government’s statement of two days ago announcing a committee of experts to treat the issues concerning journalism 6 months after the Daphne Caruana Galizia inquiry documented the conditions that killed her, including the ones that persist as conditions in which journalists in Malta must work.

The government’s statement is the only window we have into what they’re thinking. We have to understand it because the worst-case outcome of this process is not that threats to media freedom are not addressed and the problems remain the same. The worst case (and frankly the very likely) outcome is that things get worse.

The easiest way out for the government on this is that they feel free enough to proclaim they cured the country of the illnesses diagnosed by the inquiry.

Assume that’s what they want.

Minutes after Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed, Joseph Muscat told the world “this is not Malta”. Days later he flew to Dubai to sell passports telling the world “it’s business as usual”. They have been saying there’s nothing wrong with press freedom in Malta throughout. The inquiry reversed that trend and became the first state institution to diagnose the problem. And now all they would want is to put the false sense of security and normality back on track.

Here’s another observation from the statement of two days ago.

The government say:

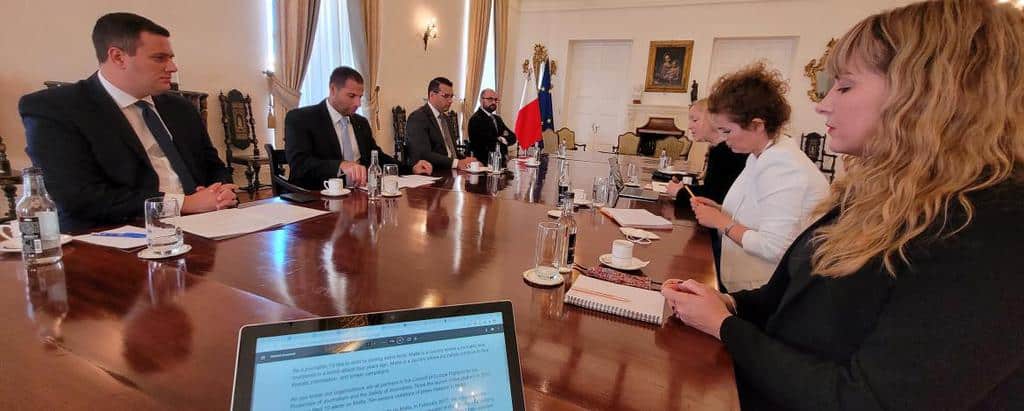

… the Office of the Prime Minister has been holding consultations to ensure swift and timely implementation of the recommendations. Meetings were held between Prime Minister Robert Abela and key stakeholders, including the Caruana Galizia family and their legal representatives, the Institute of Maltese Journalists (IĠM) and members of international organisations like Article 19. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, the European Commission, the European Parliament LIBE Democracy, and the Rule of Law and Fundamental Rights Monitoring Group (DFRMG) were also kept abreast of developments.

Look, you and I probably never expected to be invited by the prime minister so we tell him what we think. He can’t meet everyone with an opinion, which means he needs to be selective. He’s got other things he’s busy with. This is not then to suggest his list of face-to-face meetings to consult on media reforms is in any way incomplete.

But I think it’s fair to say that the safety of journalists, the management of threats to media freedom, the state’s obligation to be transparent and to submit itself to public scrutiny, and the state’s obligation to protect media freedom as a pillar of democracy are a matter of public interest. The interest is as public as they come. It concerns the very mechanics of democracy.

We understand the restrictions of representative democracy. We don’t get to speak in Parliament or in a court room because we’re interested in what is being discussed there. But it’s a principle of democratic government that we’re allowed to go in to listen and then, in appropriate fora outside, to say what we think. If parliament and the courts must conduct their business openly, why do the government feel entitled to discuss the very fundamentals of democracy inside locked up rooms, exchange documents with the people they consult marked private and confidential?

All the government have let us know about these “consultations” is a checklist of meetings the government have had. We don’t know what was said in those meetings, though we can imagine. What we definitely cannot know is what of all that they have been told by the consultees, the government have ignored or discarded.

That takes me to my second observation on the government’s statement. They say they have given the committee of experts a set of legislative proposals ostensibly intended to implement the findings of the inquiry. The government did not publish the proposals. They listed instead a brief summary of what they intend to do. A face value assessment of the list is that it is incomplete, it is not thought through, it leaves out very serious risks to press freedom, and is nowhere near what it needs to be.

It’s not right however to be so critical when I haven’t actually seen the drafts. The devil, as they say, is in the detail, and I have not seen any of that at all. No one outside the committee it seems has. Why is a process which is in and of itself about transparency being conducted in such a suspiciously opaque manner?

Never mind what you and I might say. Why should Article 19 et alia and the other entities the government have met not be able to see what the government have done with the advice they gave them? Why should we not be able to hear what they make of this?

Why should the government not care that their critics are reassured by what they claim they are doing to protect them and the exercise of their profession? After all, isn’t this why all of this talk of reform is happening?

Please, Mr Government, publish the “proposals” you made to the committee so we can tell you what we think too.