Party leaders get to assign areas of responsibility to their parliamentary group. It’s all a dress rehearsal for the exercise of the prime minister’s prerogative that in our rules gives him or her complete hire and fire rules on government ministers while obviously he or she are held by the hire and fire discretion of his own party.

Party leaders wield great power over those immediately under them but over them is the power of the entire party. Party members are rarely aware of their own authority which makes the leader’s discretion feel infinite.

Reshuffles are painful processes and if anyone attempts to go through one of those with everyone emerging pleased and satisfied from the room, they’re doing it wrong. Ministers and shadow ministers are people with sore and touchy egos, easily bruised by real or perceived diminishment.

Even though I share views and experiences of many years with people diminished by Adrian Delia’s choices yesterday, I don’t think any analysis coloured by emotional attachment to someone’s career ambitions is of any use.

Including of course the party leader’s own.

New party leaders are keen to assert their authority. They are keen to ensure party cohesion but not at the expense of their political vision. They will promote those who support it and relegate those who do not. It is the natural order of things. If the leader’s formula gains the right electoral result, the outcome justifies the pain of the road to get there. If it doesn’t, he or she must carry the can.

However, a party leader’s discretion, conceding it is as near absolute as one can imagine, is not itself beyond analysis and criticism.

Adrian Delia took the unusual step of retaining a specific subject area in his own competence. Prime ministers do this, rarely, when they want to send a signal that a specific area of interest is so crucial to their policy program, they would not delegate it to anyone else.

Eddie Fenech Adami for a while retained foreign affairs when his own personal charisma was needed to help European capitals outgrow the Mintoff/KMB stigma they labelled this country with. Alfred Sant retained the transition away from VAT, a fact which did not prevent the collapse in our public finances. Lawrence Gonzi retained finance when the endemic public deficit needed to be reined in to ensure alignment with criteria to join the Eurozone: probably the toughest administrative challenge this country went through in decades.

Those were prime ministers. Leaders of opposition do not traditionally shadow ministers. Their focus is the prime minister and they almost always want to project an image that debating the prime minister’s minions is beneath their dignity. Adrian Delia has departed from this.

Adrian Delia’s retention of the justice portfolio within his own direct responsibility may, by an optimist, be interpreted as a signal of prioritisation in this area. Which would be significant indeed. Increasing intensity on this area on top of Jason Azzopardi’s assiduous work in the last several months up to the day this responsibility was taken away from him would be very impressive.

Adrian Delia’s retention of the justice portfolio within his own direct responsibility may, by an optimist, be interpreted as a signal of prioritisation in this area. Which would be significant indeed. Increasing intensity on this area on top of Jason Azzopardi’s assiduous work in the last several months up to the day this responsibility was taken away from him would be very impressive.

The corruption revelations over the last years highlighted the sore weakness of our justice process and the consequent impunity. The death of Daphne Caruana Galizia has shaken civil society into bringing ‘Justice’ to the heart of their agenda. Having let Jason Azzopardi focus on this area of responsibility, Adrian Delia allowed the PN, within considerable constraints, to keep some form of presence in the discussion.

Given Adrian Delia’s baggage and how Daphne Caruana Galizia followers feel about him the PN leader had to and chose to stay in the background over the last 4 months.

Is he intending to change that? Is Adrian Delia intending to occupy justice?

And what change does he intend precisely? Is he going to take the plunge and take a front line role in combatting corruption? His position on the hospitals privatisation, though late, has not been timid. Does Adrian Delia feel confident enough in his new shoes that he can now chase civil society and lead it from the front?

To an extent his leadership team has projected an attitude over the past several weeks that they feel empowered to exercise authority inherent to their office. All they need to do is assert it. ‘We’re here now, like it or not’. This may have given them effective rewards in some places. It has consolidated the alienation of some others. My feeling remains that this new assertive self-confidence is not justified by the extent of support the PN enjoys and I cannot imagine how detractors can be made to change their mind by being bullied into submission.

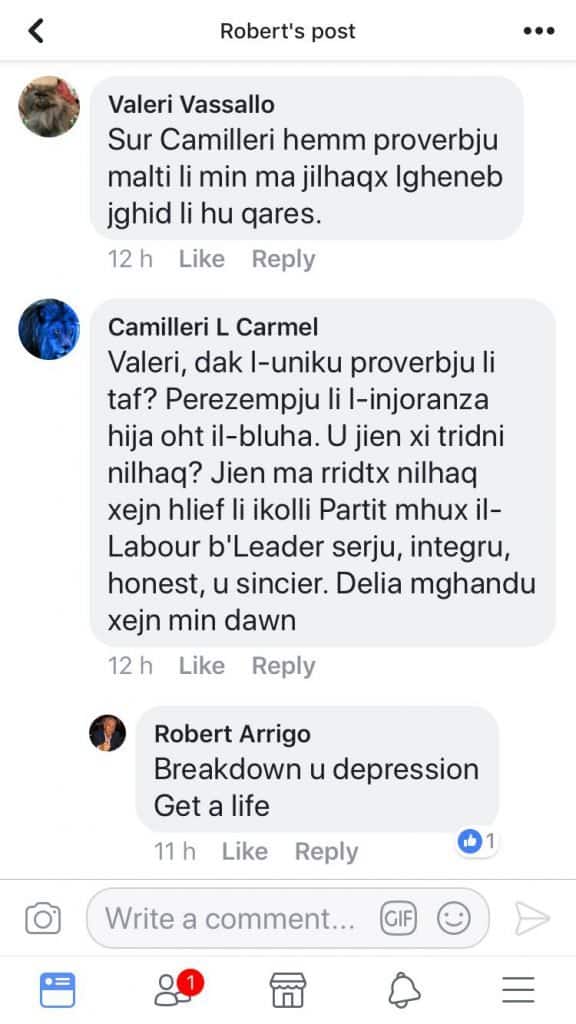

Here’s what must be a clumsy slip by deputy leader Robert Arrigo who eloquently explains away criticism of the leadership team he belongs to as a symptom of ‘depression and mental breakdown’ and that critics needed to “get a life”. Firstly it is chilling that a candidate deputy prime minister has these antediluvian notions of mental health. Perhaps his shadow minister on mental health, Mario Galea, could brief him a bit about that. But at least just as importantly does Robert Arrigo now think he has convinced anyone they may have been wrong about his and his team’s qualities to run the party and the country?

Here’s what must be a clumsy slip by deputy leader Robert Arrigo who eloquently explains away criticism of the leadership team he belongs to as a symptom of ‘depression and mental breakdown’ and that critics needed to “get a life”. Firstly it is chilling that a candidate deputy prime minister has these antediluvian notions of mental health. Perhaps his shadow minister on mental health, Mario Galea, could brief him a bit about that. But at least just as importantly does Robert Arrigo now think he has convinced anyone they may have been wrong about his and his team’s qualities to run the party and the country?

This sort of thing is not uncommon. It is also of a far lower standard than many PN voters are used to expect from their leaders. And people who worry that the party is not presenting its best at its front and centre observe for example Claudio Grech’s removal from the economy brief and the assignment of that highly crucial and strategic topic to Kristy Debono.

Those seeking for motivations in things I write will remember and remind that Claudio Grech was my office buddy and then boss and mentor for the better part of 10 years. We featured in MaltaToday cartoons as a pair of Rottweilers in Austin Gatt’s shed.

Conceding all that, his removal from the economic brief is, as it seems to me now, an objective error. As the short-term gains of Joseph Muscat’s short-term economic policies start turning sour, the PN should be bringing economic policy-making to the centre of its political discourse. As more people become disaffected by corruption and sleaze, they might only consider switching their votes to the PN if they have confidence the PN will let the good times roll.

Conceding all that, his removal from the economic brief is, as it seems to me now, an objective error. As the short-term gains of Joseph Muscat’s short-term economic policies start turning sour, the PN should be bringing economic policy-making to the centre of its political discourse. As more people become disaffected by corruption and sleaze, they might only consider switching their votes to the PN if they have confidence the PN will let the good times roll.

Can Kristy Debono instil that confidence of expert and deep understanding of economic policy making, of private and public sector experience, of academic appreciation of the subject and the innovations emerging world-wide better than Claudio Grech can?

Comparisons are obviously odious. And these are calls that a leader must make, at his own risk, even as he makes those odious comparisons and makes the choices he feels will best serve the party’s interest. Not knowing what he knows it feels like in this very strategic choice loyalty has been prized over competence and given that we’re talking about economic policy here this may have been the least wise place to play that game.