Yesterday marked Holocaust Memorial Day.

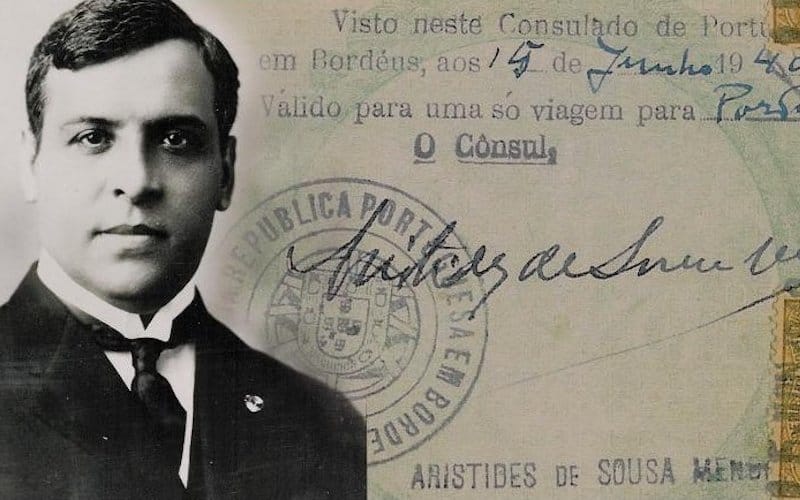

There were many articles worth reading marking the event. I was especially struck by this one on The New York Times. It tells the story of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, a Portuguese diplomat who defied his government’s orders and issued visas to Jews escaping discriminatory laws and the violence that escalated around the outbreak of the Second World War.

Hindsight blinds us to these historical situations and forces us to miss the familiarity of the case.

At the time the story told in this article unfolds, the Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution were three years in the future. The discriminatory laws against Jews living in Germany and German-occupied territories were objectively unfair but were not understood at the time to be a mortal danger. What’s more they were backed by the force of law and reflected popular will as far as anyone could make out.

Also this fellow’s country, Portugal, had every intention of staying out of the conflict that was arising in Europe. Acting to undermine German interests was not policy.

And the flood of refugees coming in was more than any small country could handle. What could Portugal be expected to do, host 6 million Jews?

Read the story of the decisions taken by Aristides de Sousa Mendes. These Oskar Schindler stories are no restoration of some faith in humanity. They are all the more depressing for their rarity. In the face of millions discriminated against, removed from their homes and their property, exiled without explanation as to what their final destination would be, governments acted on what they claimed was the basis of international law and national interest.

With few exceptions, governments ignored the fate of people whose life was at great risk.

If we remove the hindsight of the knowledge of the mass extermination of the Jews, the knowledge and risk that went into the decisions taken by Aristides de Sousa Mendes are not dissimilar to the considerations around the decisions we

Pointing out there are no extermination chambers in Ethiopia and Ghana is irrelevant. Even the excuse that people are mostly escaping from economic hardship (and should therefore be pushed back to accept

Mr Sousa Mendes was moved to act when he heard the story and the experience directly from the refugees huddled in the main square of Bordeaux where he worked as Consul. We don’t get to hear the story from the mouths of refugees very often. Sometimes there are exceptions.

You may have heard of Mamoudou Gassama, the immigrant who was made

“It’s very hard for immigrant people in Libya,” he says. “I did it and so I know how hard it is to take this path. Libya is very difficult for black African people. They beat you, they put you in jail, they kill some people, and they put some people in slavery too. There is a lot of racism there.”

Those words would have been enough for Aristides de Sousa Mendes to defy the orders of his government, give up his career, his pension and his future, and try to save as many people from their fate in Libya as he possibly could.

He’d be a rare man indeed.