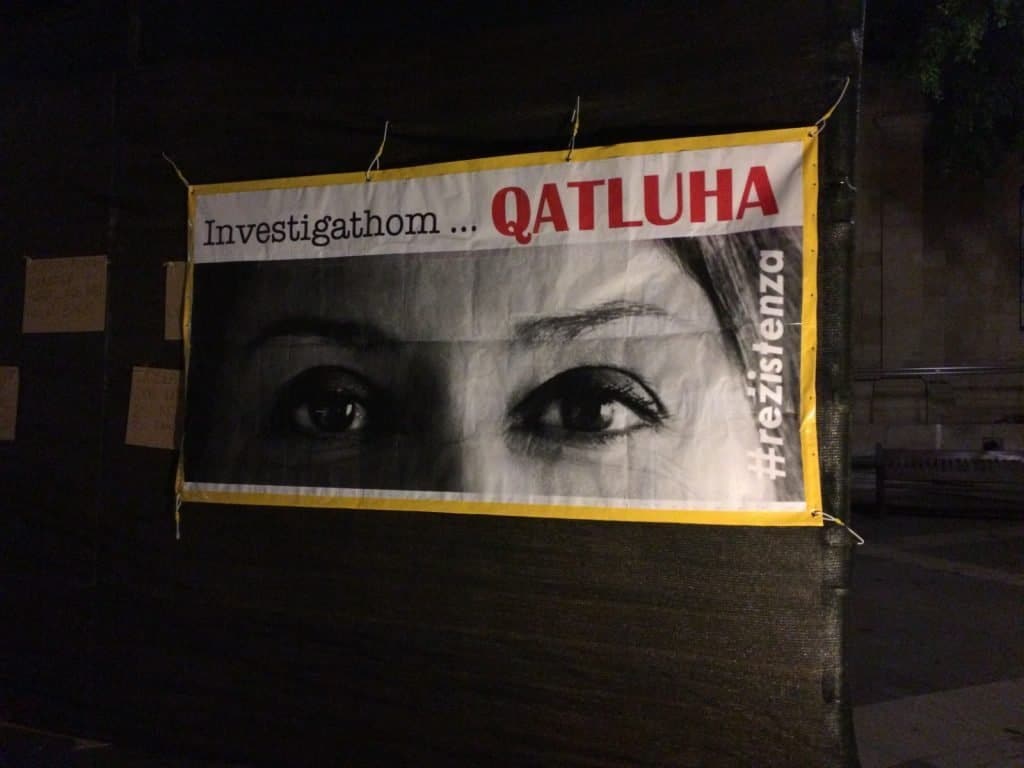

It took 20 months of campaigning, a successful court case filed by the family on another aspect of the same provision of the European Convention on Human Rights, a resolution of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, a year-long worldwide campaign of all major free speech NGOs, a petition signed by some of the most eminent literary figures in the world, editorials in leading publications of the world, a behind-the-scenes campaign with friendly governments of other countries, a daily protest in Republic Street, a speaking campaign by the sons of Daphne Caruana Galizia who toured the world campaigning for justice for their mother before they could ever think of privately mourning her, for the government to relent and accept that it cannot continue to refuse the inescapably logical imperative to have an inquiry into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

When Kurt Farrugia a few weeks ago wrote to a journalist to tell her he didn’t think Daphne was assassinated, the government had plumbed hitherto unreached Orwellian depths and illustrated perversely how self-evident the truths they were denying were.

When a journalist is killed, democracy suffers. And our democracy has not even been given the opportunity to examine why this was allowed to happen and if the danger of its repetition is as imminent as it feels. The Government that was supposed to ensure that the State asks questions of itself abdicated this fundamental responsibility.

We have not had time to ask if the State could have done more to prevent the assassination and to find out if the government even cared to learn from any mistakes.

We have not had time to understand if the current state of play in the investigations — three hitmen perhaps on the verge of walking out on bail because the bill of indictment charging them of a murder with evidence that looks iron clad is not yet drawn up and no news whatsoever about who paid them to do it — is really the best that could have been reasonably hoped for.

Our government has not yet found time to examine our own democracy to understand why it has failed us so miserably.

Of course, the off-hand way with which Carmelo Abela gave the news today, that it seems that some time somewhere his boss had said we’re to have the Public Inquiry, gets us nowhere near closure on the matter. This is only the beginning.

If someone of Philip Sciberras’ ilk is going to be given yet another supplement to their multiple pensions or other forms of tax-payer income to write a report blaming the death of Daphne Caruana Galizia on herself, peppered with some reluctant sops to how sad it is that she had to die mixed with “reasons” why she was asking for it anyway, then all we’ll have is another confirmation of how keen the government is to cover up its or someone else’s tracks.

This should be a public inquiry that reviews in detail the events and actions, particularly of the government and its assorted agencies, in the years leading up the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia and the time that has elapsed since.

The inquiry must be empowered to accept evidence and It must conduct hearings publicly.

It should not be limited to a specific event or a specific predefined set of circumstances but should be free to explore any and all considerations that are relevant to an understanding of the causes of and circumstances surrounding the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia without any limitation to the specific criminal conspiracy; and especially looking into the behaviour of the State in that time; the wider context of media freedom in Malta; an examination of the context of rule of law in Malta; the effectiveness of police action; the impact of the government’s retention of Silvio Valletta on the investigation team; the extent of and limitations to cooperation with overseas law enforcement agencies; the policy framework on the protection of journalists and how this has been impacted if at all; and so on.

The public inquiry should be able to receive evidential submissions from anyone — individuals or organisations — that on their initiative feel they have a contribution to make to the inquiry.

It should allow anyone to listen to oral evidence given by anyone else. The inquiry should allow for the fullest extent of media coverage.

The findings of the inquiry are to be documented and published. It should include an appraisal and should help us understand what happened and why. It should also include recommendations for action and resolution, particularly for government action and reform.

For these objectives to be reached the inquiry should be led by someone or a group of people whose credentials are not in doubt.

They must have clear experience in criminal matters, but also a depth of understanding of law enforcement, public administration, free speech and journalism. They cannot be seen to enjoy the favour of the government. The inquiry must be impartial, independent and objective. And must be seen to be all that, particularly by the people who have suffered most as a result of this act of violence, the family of Daphne Caruana Galizia.

The inquiry must not depend on the police or the attorney general for their resources, their administrative authority or their freedom to summon witnesses and enforce their orders.

When authorities refuse to allow the publication of any information in their possession on grounds of the ongoing criminal investigation, or other investigations or some fantasy, like national security, the inquiry should be allowed to seek judicial review of such refusal or be empowered to reject it itself.

Refusal of witnesses to answer questions or to appear in front of the inquiry on the plea that they may incriminate themselves if they were to do so are to be explicitly documented and such a plea is to be taken into account into the inquiry’s final evaluation.

The inquiry should not have a time limit imposed on it and the person or persons conducting and those assisting them administratively should be assigned to the task on a full-time basis and public hearings should be held at a minimum of pre-determined frequency.

Those are just my thoughts. I have no doubt there are several other considerations I’m not making yet. The government should closely consult Pieter Omtzigt, the rapporteur of the Council of Europe, the Venice Commission, GRECO, international free speech NGOs and the specialist attorneys representing the family of Daphne Caruana Galizia before concluding the terms of reference and opening the inquiry.

And the government should ensure the inquiry satisfies the requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights. Since we already know the Attorney General’s views on the subject, the government should ask someone who actually knows what they’re talking about.

And it must do so now. Not three months from now. Now.