Yesterday was my daughter’s 10th birthday. She crossed the first round landmark, the first decade of her life. Your 10th, your 20th, your 30th and so on are special. You want them to be. They’re the great landmarks of a lifetime. With every new decade we clock we feel luckier to have come so far. Not all of us will mark their 60th and ever fewer will cross the line at 70 and 80 and so on.

Tomorrow would have been a special day for Raymond Caruana. If he had seen his 30th birthday, tomorrow would have been his 60th. His family has lived without him now for 33 years. They have never seen justice for their great loss though there were times when they felt they were close.

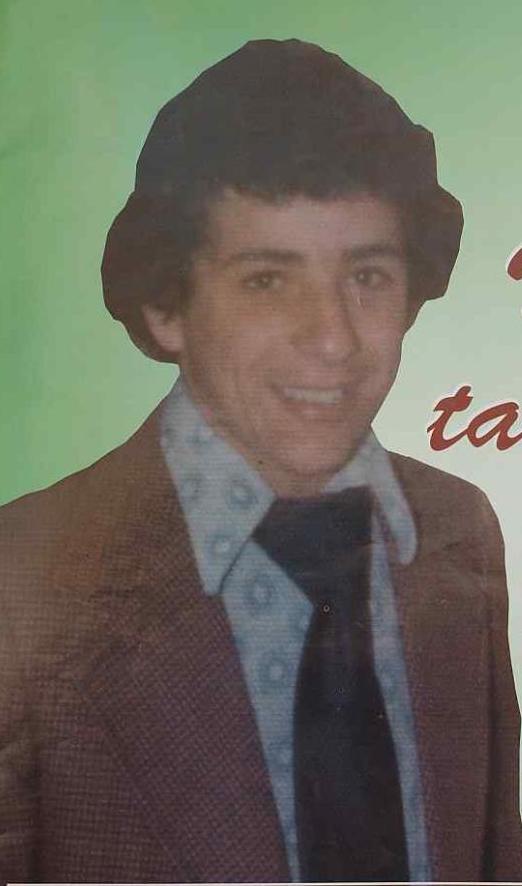

Photo: First published in Il-Mument 04.12.2011

Raymond Caruana was killed in December 1986. He was having a beer with his mates celebrating a new party club the Nationalist Party opened in his rural, diminutive, mostly quiet Gudja. It was a muted affair as celebrations go. Indoors, sheltering from pelting rain and a stormy wind that kept most people inside, even the most ardent supporters of the PN that never amounted to thousands in Labour-dominated Gudja.

A Land Rover drove by and showered the facade of the Gudja PN club with bullets. Earlier that week the same had happened to the PN club in neighbouring Tarxien. It was a very tense time. The previous Sunday the PN defied a police ban on gathering in Żejtun for a political meeting. They never made it into the Labour fortress but for daring to walk towards it on the Tal-Barrani Road they were smoked out with tear gas by the police, projectiles were flung at them, live shots were fired at them.

A later investigation would find that shots fired in Tal-Barrani came from the same sub-machine gun used to shoot at the Tarxien club. And again in Gudja. This time a bullet hit a young man in his head, killed him on the spot.

Some would say that Raymond Caruana was unlucky. He found himself in the way of a bullet aimed at no one in particular. But in reality it was aimed at him. It was aimed at his spirit of defiance that in the midst of all the horror and political turmoil at the time, still wanted to have a beer in the office of his political party.

Today, having a beer in a party club is a bit shady or sad. But in 1986 it was a dangerous and courageous choice. It was a political statement of conviction, of defiance, of individual independence and autonomy in the face of intimidation.

Raymond Caruana did not want to be shot at by a wayward bullet. But given what happened in Żejtun and Tarxien that week, he can’t have fancied his odds. That sub-machine gun was used to break the spirit of people like Raymond Caruana. It was meant to persuade them that hoping for change was futile. That power was with the people with a finger on the trigger, not the sods drinking a beer from a bottle.

Raymond Caruana was killed in December. He would have turned 27 the following May. He planned to start a new life that May. He was planning to get married and move out of his parents’ house. He would not experience the life he had been looking forward to.

But on what was meant to be his next birthday, the 9th of May 1987, change would come to an entire country instead. That day the reign of terror of the nicknamed thugs that were in the Land Rover as it drove by and shot at Raymond Caruana had come to an end.

The hope of the stubborn was rewarded. The fear of the rest had been soothed. Normality would slowly be restored to this country which would look towards Europe, towards democracy, towards the free market, towards devolution of powers, towards pluralistic media and away from policemen killing people in their police custody, a government fraternising with tyrants, a state monopoly of the airwaves, economic scarcities, and industrial-scale corruption.

That year Malta forgot to remember the 42nd anniversary of victory in Europe at the end of the Second World War. Malta was busy voting its own liberation instead.

On that 9th of May Raymond Caruana did not receive birthday gifts. But he gave his country one through a sacrifice no one bothered to ask if he was happy to make.

He, quite literally, died so we may be free.

Now that things are getting even darker than they were in 1986, we’d do well to remember Raymond Caruana’s sacrifice. Malta’s foreign policy is disturbingly comfortable consorting with criminals. Its economic policy is, in and of itself, an entrance ticket for criminals. And in place of the scarcities resulting from the corruption of the 1980s, we are choked by excesses fuelled by the corruption of today.

It is not sub-machine guns that are used to break our spirit. It is violence of another sort, far more effective and just as deadly: the silencing of dissidents, the intimidation of critics, the breaking of any opposition.

In the midst of all the fear and despair we too must find the strength Raymond Caruana had, to gather in a place sheltered from the wind and the rain, bottle of beer in hand and the hope that life will be better after next May. Or a few Mays in the future.