Political parties are required to sound humble, to speak as if they’re keen to “listen” to the messages sent to them by voters. This election brings Maltese participation rates in elections closer to European averages where voting is not compulsory and anything between 40% and 80% of the voting public casts their vote.

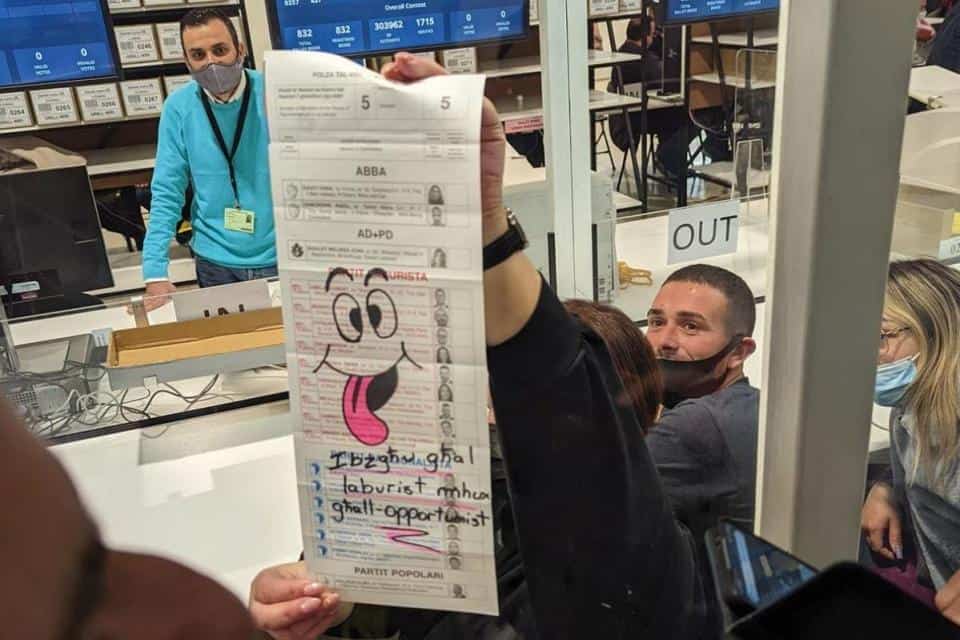

Pundits have observed that the abstention rate has doubled since 2017 as has the number of people who spoilt their votes with creative ways of saying fuck you to the political class without having the moral courage of letting people know they were not actually voting by staying at home.

As if it’s the same thing as spoiling your vote or not voting at all, these pundits have then added the votes for candidates not put forward by the PL and the PN, mostly ADPD and a smattering of others and presented the total as a devastating protest vote against the PN and the PL.

The more hopelessly optimistic added this tally to the PN’s vote and pointed out that more than half of the electorate rejected Labour.

This is warped thinking and an extremely flimsy basis for some of the conclusions that have been drawn.

In 2013, Alfred Sant fully expected to lose the EU referendum because he expected that in isolation from anything else (particularly the question of which party people would want in government) it was reasonable to expect a majority to say they would prefer EU membership. Sant needed to cast doubt on the reliability of the referendum result betting all his chips on a general election he hoped to win.

To do that he claimed to his side of opponents to EU membership all the people who did not vote or people who invalidated their vote. Including his own. Famously Alfred Sant abstained in the EU referendum and advised others to do the same.

This claim was reprehensible in principle. It was Lou Bondi, a man writing from a different phase in his life, who said his grandmother would have been apoplectic at the idea that anyone would have interpreted the fact that she was bedridden at the time of the referendum and couldn’t cast her vote as meaning that she disagreed with her beloved PN and their policy on EU membership.

The angry indignation of Nanna Olga is part of the legendarium of Maltese politics. And yet we forget the lesson from that: that it is misguided or disingenuous to make inferences about the intentions of an abstainer from the fact that they abstained.

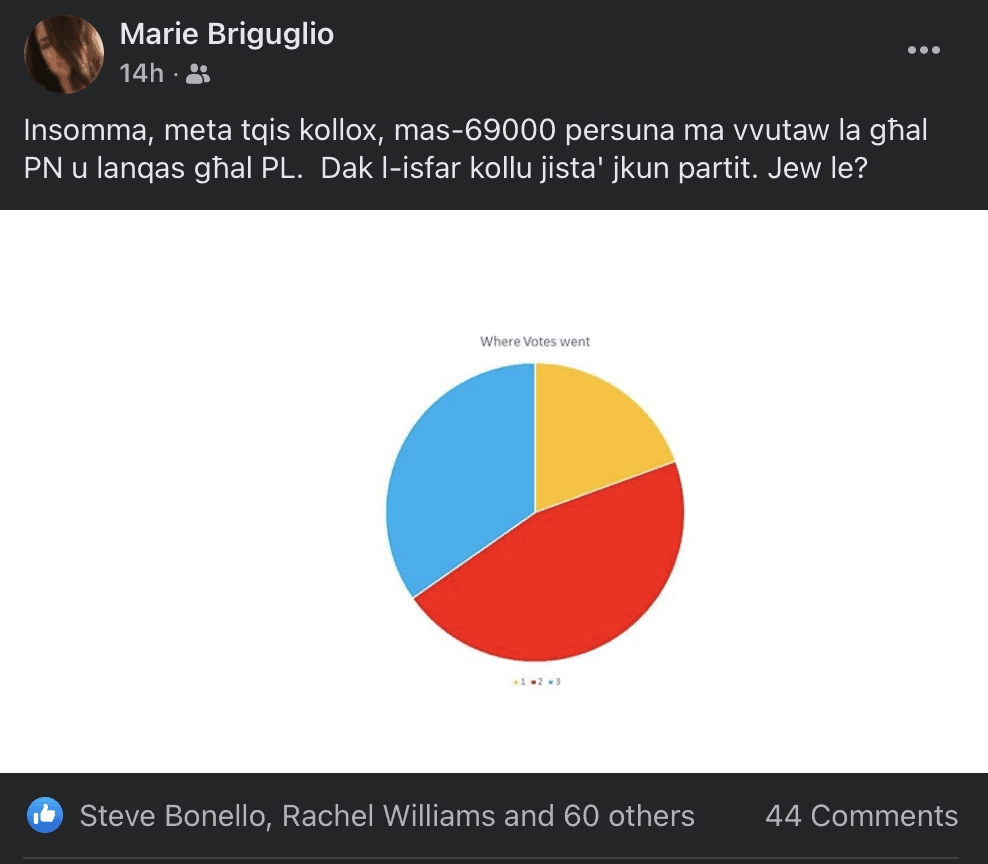

Look at this graph put up by Marie Briguglio on her Facebook post. The yellow slice of the pie is the aggregate of abstainers, vote spoilers, and small-party voters. Briguglio asks if the yellows could amount to a new political party.

Jon Mallia made a similar argument elsewhere.

Look, the doubling of the abstainers and the spoilers means that half of them were already abstainer or spoilers in 2017. The 69,000 aggregate is the difference between all the eligible voters and voters who voted for PN and PL candidates. That includes people who died between the publication of the last electoral roll and the general election. It includes people who are bedridden, people with dementia or illnesses that whether by their choice or the choice of their relatives make them unsuitable to vote.

Part of the increase over previous years can be attributed to the decisions of children of elderly parents who refused to drag them to vote on wheelchairs and on stretchers. That would be both PL and PN voters who, like most people, understood the outcome of the election to be certain and felt therefore that it was unnecessary to burden their parents with the indignity of being dragged to the polling stations.

The certainty of the outcome could have encouraged all sorts of people, even healthy ones, not to bother with participating. Some will have travelled abroad without bothering to register for early voting working out, that their effort would be immaterial. Many, who are eligible to vote but live permanently abroad, would have decided to forego the cost and the bother to fly to Malta to participate in a general election the conclusion of which was long foregone.

The intention of abstainers cannot be determined unless they’re asked. Some volunteer the information usually by responding to begging party officials on election day by remonstrating some grievance that had never been addressed.

Here’s something to think about. Abstainers who stay away from voting as a form of protest are viciously loyal to their traditional party and would not dream of voting for anyone else. They could not bring themselves to switch sides because the only thing they feel more strongly than displeasure about their habitual party is hatred of any opposite party.

They feel they are not betraying their party by not voting because in any case they did not vote for anybody else. Hardly the people looking for a new party to be elected.

Consider now vote spoilers. There are always spoilt votes and some, no doubt, are due to voter incompetence rather than wilful destruction. Again, the people who spoil their vote as a form of (carefully anonymised) protest are so loyal to their party that they would rather not vote for anyone than vote for anyone who is not running for their traditional party.

Think of the guy who famously brought in his stationery set to draw a protest cartoon on his ballot. His message was clearly and uniquely addressed to the Labour Party, the only party he would ever vote for. He’s only not voting for them this time because, as he saw it, his party is too keen on helping people not born within the tribe.

Naturally people who voted for the smaller parties have expressed an intention that one is justified in interpreting as a willingness to vote for someone who is not presented by PN or PL. The numbers have indeed grown but, let’s face it, they are still miserably few. Nowhere near the 69,000 of the “none of the above’s” shown in Marie Briguglio’s pie chart. They are far less than the (admittedly arbitrary) benchmark of 5%, which is a typical minimum threshold in many democracies who use strict proportionality to assign parliamentary seats to political parties. (I will write about that in a separate post).

Is that 69,000 a market opportunity for a new political party? Without going into the normative question on whether we should have a third political force or not, my answer is that from the evidence at hand it is impossible to answer that question with any confidence.

If both Burger King and McDonald’s lose clients, does it mean that all the people who eat at neither joint will flock to a new restaurant serving Lobster Thermidor? Do we know that people who no longer like Burger King and McDonald’s would be keen on grilled crustaceans and molten butter?

I say this because a new political party cannot form around the varying and contradictory motivations for people not to vote PL or not to vote PN.

Would the people who stayed away from voting PL because they didn’t get a permit to dig a big pool in their field, vote for a new party that campaigns against ODZ development? Will the people who stayed away from voting PN because one of their candidates said she was pro-choice, vote for a new party that campaigns for choice? Will the people who stayed away from either party because they’re not tough enough on black people, vote for a party that campaigns for the respect of human rights of undocumented migrants?

The point I’m making is that before disaffected pro-choice, green, anti-corruption liberals think that there’s a market for their opinions in the 69,000 eligible voters who did not vote either PN or PL, they need to understand why they didn’t vote.

I hazard a guess that there are very few like-minded public-spirited people in the yellow portion of the pie chart. I rather suspect that people with an altruistic desire for politics of the common good voted in the election. I rather suspect that apart from the obviously altruistic people who voted ADPD or Arnold Cassola, there are many others who voted PN or PL. In their thousands they would have evaluated their disappointments with either or both parties and voted for what they decided would be the lesser of two evils. I know I did.

Two conclusions then:

First, any interpretation of what the 69,000 might have done if there had been another party cannot rely merely on counting them up. They need to be asked for their reasons for not voting PN and PL and they need to be presented with a hypothetical third alternative (with its policies, looks, resources, and the image of its potential candidates) and asked if they would have voted for that alternative if they had the opportunity. This is not a statistical exercise but a qualitative focus to understand the intent of people. I rather suspect the findings would be depressing for anyone hoping to find in there a chunk of patriots concerned with climate change.

Second, I dislike the two-party system as much as the next guy. I’m worried we’ve come to a point that we must speak of a one-party system with the PN become a refuge to a shrinking minority. But I also think that the market for specific political ideas that can coagulate around a new political party is in the part of the population that is not in the 69,000 (less the people who voted ADPD and Arnold Cassola). Decisions are made by those who show up. It is the people who voted for someone who have a view that can, at least potentially, be changed out of persuasion and political argument.

The ‘opportunity’ for new politics has always been there, or at least since we’ve had elections. The choice to pass on that opportunity and stick to PN or PL was taken every time by the great majority of Maltese voters. Because that’s what they wanted. If there’s anyone with a better idea (and one can only hope and pray there is) they should get busy putting together the policies a new party would stand for, instead of getting busy on giving up convincing anyone who has voted for the mainstream parties to choose to change course.