I’ve been speaking to people who work in advertising to try to understand the imbalance of marketing resources and capability between the two organisations we still describe “as the two main parties”. A “two-party system” implies some sort of balance and equality of arms, a neck and neck struggle where the sides take turns winning and losing.

Even a superficial analysis of the advertising campaign around this election shows that on the one hand we have the PL, the dominant power, and on the other the PN, a sizeable minnow unequipped with anything like the sufficient resources to mount a challenge that could realistically overcome Labour.

Let’s consider a few factors.

Take billboards on the streets. The PN has less than 40 billboards. The PL has more than 250. That’s not just a display of unequal abilities or in any way an indicator that Labour has the advantage in a competition of good sense, good policies, or good organisational skills. The only difference between the two political parties demonstrated by the inequality of arms is their different access to money. A big difference.

Conservatively each billboard costs about €2,000. At 250, that’s €500,000. For completeness’ sake some of that money did not have to be raised by the Labour Party. They’re advertising on space hogged for months by the pointless Film Commission adverts promoting the pointless Film Awards. But it should hardly make you feel better to learn that you must pay out of your tax contributions for some of the costs that go into an elaborate swindle at your expense.

They change the artwork on those billboards every 5 days or so, that’s 7 times for the duration of the campaign, spending a conservative estimate of €500 for every poster they stick to every billboard. That’s €875,000 in artwork: nearly €1.4 million spent on an overwhelming physical domination on the highways of Malta and Gozo.

On top of the billboards there are the street banners that industry professionals estimate cost around €200,000.

An earlier post on this blog spoke about the battle raging on online. I say battle. ‘Battle’ implies any side stands the risk of being overwhelmed by the other but it’s really a case of bows and arrows against lightning. The only conclusion to be drawn every time you open a website that carries Google Ads is just how crushing the overwhelming domination of Labour is. I spoke to industry professionals who tell me Labour must be spending in the region of €80,000 a day on online advertising, that’s €2.8 million by the date of the election. Maybe considerably more than that.

Now consider these other elements.

Labour is not just booking advertising space online with a greater budget than its competitor. That would just mean there would be more Labour adverts than PN adverts but the PN adverts would still have a presence that is proportionate to their spend. To prevent that, Labour is using a Google feature that allows them to pay whatever it costs to ensure that their adverts are carried while everybody else’s are drowned out.

A face value assessment of the online advertising output shows the PN’s advertising exposure is outscaled by the PL’s by a factor of 10. For people who perceive reality nearly exclusively through their exposure to what’s online (particularly younger voters in the 16 to 25 bracket) the PL is 10 times as large as the PN, because its adverts are 10 times as present. Some will find the PL 10 times as annoying as the PN. Most will take it as a given that the PN is not worthy of their consideration simply because it is nowhere near as domineering and dominating.

In money terms, this is costing Labour far more than even the most aggressive online campaign would. Industry professionals tell me this is not merely choking out the much poorer PN. It is choking out the private sector that is unable to advertise its products online while Labour hogs all the space.

Consider next Labour’s daily campaign events, the televised chinwags in ambulatory outdoor TV studios. Conservatively, they are spending some €20,000 for each of their outdoor events. That’s just considering the PL’s events that are far glitzier than anything the PN is mustering with its obviously much smaller budget. Even events by individual Labour Party candidates are often more ostentatiously expensive than anything the PN manages to put together for Bernard Grech.

But sticking to the campaign of the PL proper and putting aside what the candidates are managing to set up, Labour’s events budget is estimated by industry professionals who spoke to me to stand at around €700,000.

Add that all up and the campaign cost for physical and digital marketing and advertising likely stands at well over €5 million.

That’s apart from Labour’s extremely well-resourced cold phone call campaign. With two weeks still to go, Labour is managing thousands of outgoing calls to households soliciting votes and offering to meet any demand in exchange.

We’ll need to wait a few more days to see what the parties’ relative budgets for physical mail drops will yield. But we know the Labour Party will have a leg-up from the government it controls. Cheques for tax rebates are due in the post in the last days before the election. Whatever the PN ends up sending to your letterbox, you can bet it won’t be a bag of money.

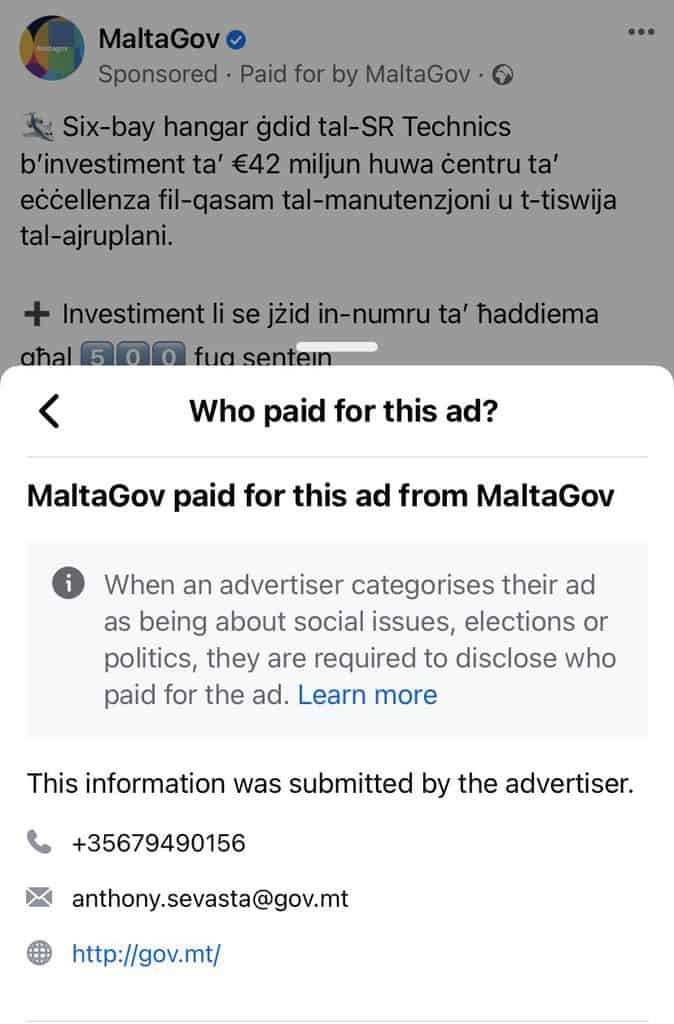

In the meantime, the government (not the Labour Party) is also spending public money bang in the middle of the election campaign to buy advertising space on Facebook. It is not as easy to flood Facebook with adverts at the expense of competing political parties as it is to do so through Google Ads, but the government makes up for that by piling sponsored Facebook adverts above the party’s budget ensuring there’s no reasonable competitive opportunity for any rival to the Labour Party.

Faced by this disproportionate firepower, the PN has been increasingly experiencing the barriers to entry into Malta’s political landscape historically reserved for very small third parties. Third parties, including long standing movements like AD (now ADPD), for years complained that the resource gap meant that people would in their voting behaviour fulfil the prophecy that a political party that cannot afford massive advertising spending would not make for a good government.

That is why though we have third parties, we described our system as a perennial duopoly.

Across general elections since 2013, and particularly so in the present election campaign, Labour is managing to propagate the broadly held view that it is in effect competing alone and it is the natural choice for a resounding electoral victory not because it has better policies or better political leaders but simply because there is no other alternative.

We may have a PN opposition but the barriers restricting its ability to access voters are so financially prohibitive that we are in effect reduced to a one-party system. That’s without the dark implications of the fact that we don’t quite know where Labour is getting all this money from and what it is that these faceless funders dodging campaign funding laws expect in return.

Such a state of play puts in doubt the very basis of free elections. To have free elections, the electorate must be able to choose from between multiple political forces (at the very least, two) that can communicate their ideas in a pluralist and fair environment. Instead, for a third general election in a row, we are faced by one party capturing the state by buying a general election with money from faceless donors.